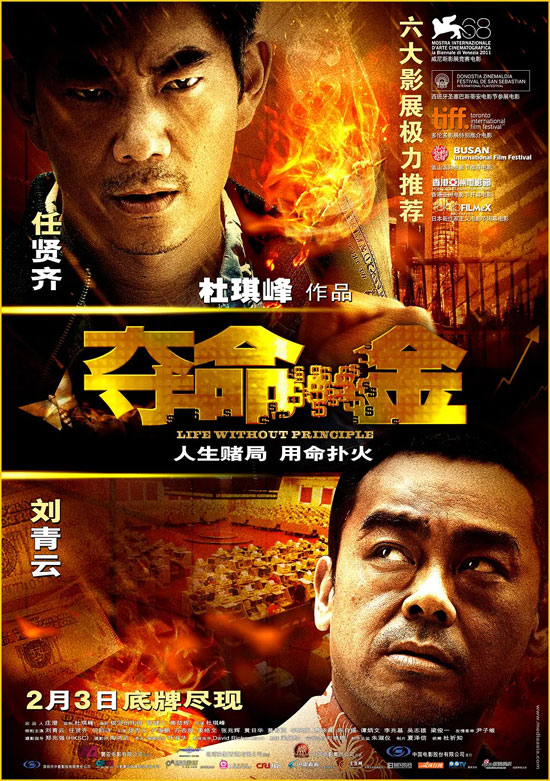

Film Name: 夺命金 / Life Without Principle / Dyut meng gam / 奪命金

After watching “Punished” for the second time, my impressions feel relatively complete, so I might as well share a few thoughts.

My strongest takeaway from this film is the director’s remarkable achievement in portraying a genuine Hong Kong within today’s cinematic landscape. This “authenticity” stands in contrast to the “Hong Kong” typically portrayed in genre films. Such realism represents an act of honesty and responsibility toward a city (a film like this could only be made by someone who has experienced its pain firsthand). This rarity is significant not only for Hong Kong cinema but also for Johnnie To himself.

How much interest do audiences still have in the “Hong Kong” depicted in genre films? Consider Eric Tsang’s “I Love Hong Kong” from years ago and Pang Ho-cheung’s “Dream Home” from two years prior (both films similarly use “Hong Kong” as their entry point, carrying a somewhat subjective “city” motif). The former still follows the 1980s family-friendly formula, wrapped in human warmth; while the latter wraps itself in “livelihood” themes to deliver a bloodthirsty film.

Though these films remain popular to some extent (whether it’s the sugar-coated sentimentality or the cathartic violence of murdering for property—local audiences seem receptive), it’s fair to say that despite their urban themes, they are utterly “hypocritical” compared to typical genre films. They show no genuine concern for the city’s transformative forces or its inhabitants. In truth, every discussion of the city within these films is a hypocritical sham—a case of putting up a facade while peddling something entirely different.

In truth, over Hong Kong’s past 15 years of transformation, filmmakers who genuinely engage with the city through the lens of “Hong Kong cinema” remain as rare as hen’s teeth. Punished’s significance lies precisely in its courage and commitment. The Hong Kong depicted here is chaotic and overcrowded, noisy and restless, with suffocating dark clouds hanging over Victoria Harbour. The film depicts the city’s obsession with money with unparalleled precision. Examine its subtle details, and you’ll find the director’s profound love for this “city” intertwined with his sharp criticism. Recall the scene where the character played by Jiang Haowen, the bulging-eyed Dragon, dies amidst a crowd. Hong Kong men and women scramble to take photos with their phones, eagerly discussing the spectacle. This mirrors countless recent mainland news reports. If you still believe in the “human warmth” portrayed in genre films about Hong Kongers, you might be reluctant to admit that Hong Kongers—and more alarmingly, the next generation—have become terminally selfish, cold, and ruthless.

So “Punished” is a rare gem among Hong Kong films. While mainstream cinema might typically approach this city through genre lenses (like the earlier “Overheard 2”), the effect pales in comparison to the starkly realistic, detached tone of this film.

Next, let’s discuss how “Punished” represents a rare departure for director Johnnie To. Everyone can see how different Johnnie is this time. He clearly hasn’t used his past lighting setups (since the film has few night scenes), hasn’t employed his usual complex staging (how could he stage a scene with Denise Ho confined to a tiny cubicle?), and hasn’t maintained his signature minimalist visuals (replaced instead by numerous extras moving about and chaotic backgrounds)… Setting aside the fact that an established director like Johnnie Woo could easily coast on his signature techniques without seeking change, can we, when observing these shifts, truly grasp the immense difficulty and challenge such transformation poses for a filmmaker with a fixed style? How much effort must be invested to achieve this?

With more daytime scenes, Johnnie no longer relies on lighting to block out residual elements in the frame (as he himself puts it, lighting is for “emphasizing what you want to see and hiding what you don’t”). This time, he must learn to control the increasing number of unavoidable elements within the shot; Heung Sze’s scenes were largely confined to cramped compartments. Whether with Lo Hoi-pang or So Heng-shuen, the dialogue unfolded with the two seated together. This approach effectively boxed him in—how could he position the camera? How could he direct the actors’ movements? No room to maneuver, or is it Johnnie To? With numerous extras—the bank scenes alone feature countless background actors—how does one manage their positioning? (For a director who emphasizes composition, To’s signature touch remains evident here.)

So while it’s easy to say Johnnie To “has changed,” the real question is the immense effort behind it—as a director, how far he pushed himself to tackle unfamiliar approaches, constantly forcing himself to overcome unprecedented challenges. This is what makes this film so remarkable for Johnnie To. The courage displayed by a 56-year-old successful director, in my view, commands respect. We can also observe Johnnie’s learning in dramatic storytelling. Take the scenes with Denise Ho in the cramped compartment—no blocking, limited space, minimal camera movement, no special lighting. How does one make this compelling? Johnnie delivers a satisfying answer through dramatic experimentation. The dialogue between Su Xingxuan and Denise Ho is quite lengthy. Even the recording of the contract signing is repeated several times from start to finish. Some viewers might find it a bit tedious (why not cut out the repetitive dialogue?). The truth is, without this meticulous, documentary-style documentation of the process—without these repeated takes of the recording dialogue—you simply couldn’t grasp how utterly absurd, twisted, grotesque, and cruel this seemingly authentic scenario truly is… And this “realistic” portrayal of society, of real Hong Kong, is far more terrifying than the scenario itself.

We also observe how Johnnie To deliberately employs a realistic approach for the two storylines featuring Denise Ho and Ren Xianqi, while handling the Tony Leung storyline with absurdity. This method itself is quite risky (as the two styles clash), but To masterfully unifies them all under a single, theme-driven “absurd” tone. Lau Ching-wan’s thread embodies “overt absurdity,” while Denise Ho and Ren Xianqi’s represents “covert absurdity.” The bank transaction’s absurdity rivals Lau’s exaggerated facial expressions, while Ren suddenly acquiring a five- or six-year-old sister reveals the absurdity of the preceding generation—revealing that the seeds of Hong Kong’s madness were sown long ago.

Additionally, a few noteworthy points: one is Johnnie To’s use of sound, this time emphasizing the irony of music—singing lighthearted harmonies at the most absurd moments, much like the elegant instrument (what’s it called?) played by Hong Wai-leung (the hotel clerk) before the birthday banquet. The irony couldn’t be more obvious. Background sounds—TVs, phones, radios—permeate the entire film, further amplifying the chaotic, cluttered atmosphere the movie demands. Another point: when the theme music begins at the end, Johnnie To unexpectedly employs the French New Wave-era fashionable documentary technique of freeze-frame (admittedly, the expression on the frozen girl’s face is genuinely laughable). If memory serves, I don’t recall To using this technique before, which is genuinely surprising. I wonder if it was the director’s own idea or the editor’s decision.

As for the film itself, “Punished” isn’t the kind of movie packed with climactic moments, nor does it possess the meticulously crafted visual atmosphere of Johnnie To’s earlier works that invites careful appreciation. What deserves praise, however, is the film’s perspective and themes, the bold changes Johnnie To has made. most importantly, he remains worthy of the title “Hong Kong director” (a label many no longer deserve). His heart for this city remains as pure as ever, leaving us no reason to lose faith in him. Especially when we speak of our love for Hong Kong cinema, we can confidently declare: Johnnie Woo is still here.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Punished 1991 Film Review: A Real Hong Kong