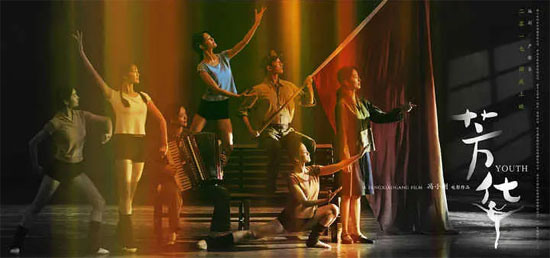

Film Name:芳華 / Youth

Last night, I stumbled upon a sneak preview of “Youth” at a nearby theater and immediately decided to catch it.

Though it was over two months late, my curiosity and anticipation for this film remained undiminished. After watching it, I became even more certain that the earlier emergency rescheduling was purely due to unavoidable circumstances beyond anyone’s control—it was definitely not some marketing ploy. Otherwise, it would have been far too costly.

Regardless of Feng Xiaogang’s directorial prowess, one thing must be acknowledged: he genuinely pursues artistic vision. While making comedies for profit, he remains fixated on tackling less commercially appealing dramas. Would someone without ambition bother to fire off such relentless “small-caliber artillery”?

Regarding “Youth” itself, the original novel by Yan Geling carries more weight than one might imagine. Feng adapted it with changes that likely served the film better. While the film didn’t deeply move me, it did sufficiently convey the era’s “sentiment” for me to understand.

[Spoiler Alert: The following contains spoilers.]

It’s no exaggeration to call “Youth” the previous generation’s “To Youth.” Having come from an army cultural troupe himself in his youth, Feng Xiaogang’s decision to set the story’s main stage within a military cultural troupe is a blatant case of personal agenda.

What struck me most about the film was its use of color. Unlike Zhang Yimou’s bold and flamboyant approach, Feng Xiaogang never overemphasizes color. Yet in “Youth,” even a brief glimpse of his distinctive palette leaves an indelible impression.

The film’s underlying tone is “green,” composed of the olive drab of military uniforms, the vibrant green of the environment, and the tender green of youth. Simultaneously, the film weaves in countless, indescribable hints of “springtime hues.” It unapologetically portrays and yearns for vibrant, beautiful bodies—white thighs, faintly visible torsos—these colors interspersed among the greenery form dazzling, eye-catching flashes of brightness.

Of course, neither green nor spring hues overshadow the dominant theme—the primary color in the film’s first half is “red.” It is the color of the vivid banner at the center of the stage, the color of ubiquitous era-defining elements, and above all, the color that resonates in the hearts and spirits of countless individuals.

In daily life, from waking to sleeping, every member of the cultural troupe is inescapably surrounded by red… It is precisely for this reason that the black curtain hung after the Great Leader’s passing in 1976 feels so jarringly out of place, piercing the heart and soul.

The meaning of red in the film extends beyond this. It constantly aids in narrative and atmosphere building, subtly shifting the dominant color to “white” in the latter half.

For instance, when the troupe members secretly listen to Teresa Teng’s songs, the red cloth Chen Can drapes over them to “set the mood” clearly carries an additional layer of hazy ambiguity and intoxicating enchantment.

Yet no matter how many meanings red embodies, they all revolve around passion, fervor, positivity, and revolution.

Regardless of the original novel, the protagonists in the film “Youth” are Liu Feng and He Xiaoping, leaving Xiao Suizi’s position as the “perspective character” somewhat awkward. Yet purely in terms of “color involvement,” she is indeed the character best suited to carry this weight, as she appears in nearly every scene featuring significant color shifts.

When the cultural troupe was at its zenith, she danced the lead role in the group dance, waving a red flag. When the troupe faced uncertainty, it was she who ran past the poolside, her bedsheets as pale as white mourning cloth…

As the era transformed, residents of the military compound underwent involuntary changes. This “shift from red to white” unfolded silently, yet traces remained in Xiao Suizi: she was both the dancer in white attire holding a red flag and the audience member in a white bodysuit plunging into the red curtain.

This “color contrast” manifested in both significant and subtle ways.

For Xiao Suizi, the best days were probably when she was secretly in love with Chen Can. Biting into the red tomatoes he’d picked for her, even working late into the night on the bulletin board felt not bitter at all, but instead filled with a sweet and sour fragrance.

But in the new era, Liu Feng, once the paragon of virtue, gradually became the universal adhesive everyone referred to—capable of sticking even to an outcast like He Xiaoping, whom everyone despised… Xiao Suizi seemed like a window between two worlds. The white ice cream she spoke of was undoubtedly sweet, yet it melted far too easily.

As the film progressed toward its conclusion, the dominant white palette gradually faded, ultimately dissolving into the familiar yet subdued hues of everyday life—memories have color, but inevitably shift from vivid to muted, from reverie to reality.

Returning to the story of “Youth,” what resonates most is its authenticity.

During the Cultural Revolution, due to his family background, my father—strong and eager to enlist—couldn’t fulfill his dream of joining the army. Decades later, even today, I can still hear the longing and yearning for military life in his words. In that era, for countless people, the identity of a soldier was supremely sacred and a source of immense family pride. Thus, it’s easy to understand He Xiaoping’s motivation for stealing the military uniform to take photos.

This “military uniform incident” also laid the groundwork for many future conflicts and revealed the characters’ true colors: the lonely and helpless He Xiaoping, the aggressive Hao Shuwen, the hesitant Lin Dingding, the righteous Xiao Suizi, and others.

As for the objectively existing reality of “asceticism,” while the film touches upon it, it doesn’t delve deeply. It merely skims the surface in a few scenes—like the crude homemade breast pads that sparked another wave of criticism against He Xiaoping.

The film contains numerous “inconsistencies” that undermine the impact of certain portrayals, even making them seem incongruous. Yet upon reflection, this precisely mirrors reality—where positions are rarely black-and-white, but more often exist in a gray zone blending good and bad.

Both children of high-ranking military officials, Hao Shuwen was arrogant and domineering, always acting like a de facto team leader and bossing others around. Chen Can, however, kept a low profile and never made a fuss. Yet, not long after learning about Chen Can’s family background, Hao Shuwen—who had always disliked him—began to develop feelings for him.

Xiao Suizi, who had long harbored a secret crush on Chen Can, immediately stowed away her newly penned love letter and the budding affection that had begun to overflow upon learning her roommate had “snatched the prize.” She tacitly accepted this bizarre principle of “first come, first served.”

During the bleakest days before the cultural troupe disbanded, a pessimistic, apocalyptic atmosphere permeated everywhere. Morale was low, everyone scrambled for their own paths, as if those who clung to the collective until the end would be the ultimate fools. Yet on the very night of the farewell dinner and drinks, everyone wept uncontrollably, overcome with emotion.

The selfish impulse to abandon ship and the collective grief for the group coexist authentically—they are not mutually exclusive.

The most poignant truth in Youth lies in the starkly divergent paths taken by Liu Feng and He Xiaoping, whose destinies ultimately converge.

Known as the “living Lei Feng,” Liu Feng’s selfless devotion to helping others made him seem almost otherworldly. It was only when he finally revealed his deepest personal desire—his admiration for Lin Dingding—that he truly became a more flesh-and-blood character.

Yet precisely because Liu Feng’s “persona” had been so deeply ingrained in people’s minds, it terrified the bewildered and flustered Lin Dingding. The moral halo also meant moral shackles, the deeper the halo, the tighter the shackles. Her panic and dread overwhelmed her joy and shyness—compounded by being caught in the act. Remember, back then, even if everyone listened to Teresa Teng, they could only do so in secret. Thus, she ultimately “kicked him while he was down.”

Calling Lin Dingding a “bitch” isn’t wrong, but I believe it’s also true that she later felt sorrow and regret over Lin Feng’s plight.

He Xiaoping, who had always been overlooked in the cultural troupe, took a different path.

Her few “misdeeds” upon joining the unit, coupled with her naturally profuse sweating, made her the prime target for exclusion and ridicule. Yet she endured it all, sustained by the two people she cared about deeply—her biological father and Liu Feng. When both left her, her spirit shattered, and she willingly exiled herself within the troupe. Thus, it was both strange and not strange at all that both Liu Feng and He Xiaoping ended up on the battlefield.

Liu Feng yearned to die on the battlefield. With his heart already dead, living on was merely prolonging his agony. If he sacrificed himself, he might become an immortal legend in the songs of his beloved.

He Xiaoping similarly hoped to burn her entire essence in the field hospital. Having encountered too few meaningful people and deeds in her life, she was determined to give her all to this moment… Yet in the end, this humble flame was magnified into a model story. She became the very embodiment of Liu Feng’s initial aspirations—a profoundly ironic contrast that proved to be the final straw that broke her spirit.

Liu Feng and He Xiaoping walked two divergent paths: Liu Feng transformed from a promising model soldier into a disabled veteran who “survived by misfortune,” while He Xiaoping evolved from a disillusioned janitor into a battlefield hero saving lives.

Yet they shared one similarity: neither the white bandage on a crimson wound nor the blood-stained white coat was the outcome they desired.

“Those who have never been treated kindly are the ones who recognize kindness best and cherish it most.”

Compared to her father, whose face she had long forgotten, Liu Feng—the man who brought her to the cultural troupe and treated her with constant warmth and kindness—was the only person He Xiaoping could never let go of.

Within that cherished collective where she had poured her heart and soul, a single reversal of fortune transformed all those demanding smiles into scorn and avoidance. Even the “stigma of kindness” she herself discarded like worn-out shoes was remembered by only one person—the very one who saw her off as she left the troupe. To Liu Feng, He Xiaoping was equally irreplaceable.

“They never married, yet treated each other with warmth, clinging to one another for life.” Though I silently repeated countless times before the film’s end that “the outcome doesn’t truly matter,” witnessing them finally reunite still filled me with waves of contentment.

Having praised so many strengths, Feng Xiaogang’s “flaws” remain evident: overly straightforward, chronological storytelling, along with fragmented and slightly uncontrolled handling of key points and details. These issues might have been forgivable in his earlier “Feng-style comedies,” but they feel awkward in a serious drama. While the overall experience is pleasant, it lacks truly gripping moments or a clear focal point. Coupled with its overly “realistic and complex” portrayal of reality, it genuinely misses that distinctive spirit of the era.

I suppose this is the gap between “good” and “great” that stands before Director Feng.

Still, we shouldn’t be too harsh. It seems “Youth” isn’t trying to glorify or condemn anything; it simply aims to present a specific memory of an era.

This memory is like those old photographs—once vivid and dazzling, yet gradually fading and yellowing with time… But no matter what, the outlines and faces captured in those pictures will never fade away with the colors.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Youth 芳華 2017 Film Review: Memories of youth may fade, but they never vanish.