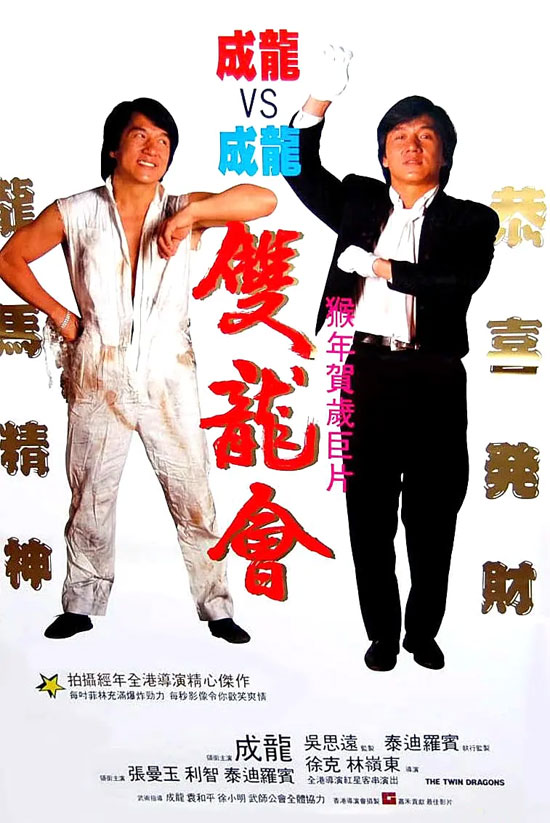

Film Name: 双龙会 / Twin Dragons / 雙龍會

Recently I’ve been reading Wei Junzi’s “Hong Kong Film Analysis,” where a passage mentions the film “Twin Dragons.” Only then did I learn this movie was produced to raise funds for the Hong Kong Directors Guild to purchase and construct a new building. “Apart from Maggie Cheung and Michelle Reis, all other roles—major and minor, even extras—were played by the directors themselves.” Reading this, my mind drifted to the film’s star—Jackie Chan. Then it dawned on me: the film began shooting in 1991, by which time Chan had long been a household name, already wearing multiple hats as producer, director, and actor. Yet his dazzling presence on screen often overshadowed his achievements behind the camera.

This anecdote rekindled my interest in the film, prompting me to revisit it. Back then, I was utterly captivated by this genre of Hong Kong commercial cinema, and my fascination remains undiminished today. Since the film was produced to raise funds for a building project, box office success was naturally paramount. Understanding this purpose lent a fresh perspective to my viewing experience. In recent years, with China’s booming film market and the proliferation of commercial films, I’ve come to understand that simply packing a movie with commercial elements doesn’t guarantee box office success—especially for films burdened by profit pressures, whose final earnings often fall short of expectations.

This film, however, stands as a model of commercial cinema. Its masterful integration of various commercial elements showcases the expertise of that generation of Hong Kong filmmakers in crafting commercially driven pictures. The plot is conventional yet not trite, with suspense and climaxes densely packed yet never chaotic. The seamless orchestration of seemingly chaotic entertainment elements reveals the filmmakers’ ingenuity. The climactic garage battle scene is particularly brilliant, where all the gimmicks and setups from earlier scenes explode into full effect. The gimmicks—Wan Ming and Ma You’s identical twin-like appearance, their differing skill levels, and their synchronized physical movements—are brought to life through spatial transitions and the bewildered reactions of other characters who are clueless about the situation. This scene is both serious and comical, brimming with wit, propelling the film to its climax. How could audiences not love such a film? How could it not become a benchmark in fashion-action cinema?

In truth, prioritizing entertainment doesn’t justify shoddy production or disposable content. Instead, films must possess that stroke of genius, compelling audiences to revisit them endlessly. Only then can they stand out in a crowded market and fierce competition, securing box office success. This was the hard-earned craft honed by Hong Kong filmmakers during the golden age of Hong Kong cinema—and what I admire most about them. Yet today, many Chinese commercial films—despite massive budgets, star-studded casts, and dazzling box office numbers—leave viewers with little desire to revisit them. Their disposable nature is glaringly obvious. It seems that while vast markets can offer expansive creative space, they also breed complacent artists content to coast on past glories. Truly, it’s a helpless situation.

This film was likely shot during Jackie Chan’s prime. Watching it, I felt he delivered with effortless ease—whether in action sequences or dramatic scenes, comedy or serious roles. Back then, he was truly full of life and energy, a joy to watch. It’s a stark contrast to his recent films, where he often seems visibly aged and struggling to keep up. Upon revisiting this film, I realized that the style and tropes in Jackie Chan’s modern action films haven’t changed much. If you compare his recent modern action films with those from his prime, you’ll find his action sequences and style are remarkably consistent and virtually identical. So why do his older films always seem more captivating? After much thought, I recalled Han Songluo’s “Wei Liao Bao Chou Kan Dian Ying” (A Film Reviewer’s Diary), which included an essay titled “The Supernatural Power of Youth.” It posits that youth possesses a supernatural power—a magnetic field that leaves a trail of destruction wherever it goes. But youth is fleeting; once time takes its toll, that power fades. Even the mightiest Asura eventually expires. Jackie Chan in “Twin Dragons” was undoubtedly such a youthful Asura. No matter how clichéd the plot or how cheesy the scenes, he infused them with boundless charisma and limitless charm. He conquered anyone, anytime, standing tall against all obstacles.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Twin Dragons 1992 Film Review: Business acumen and the young Asura