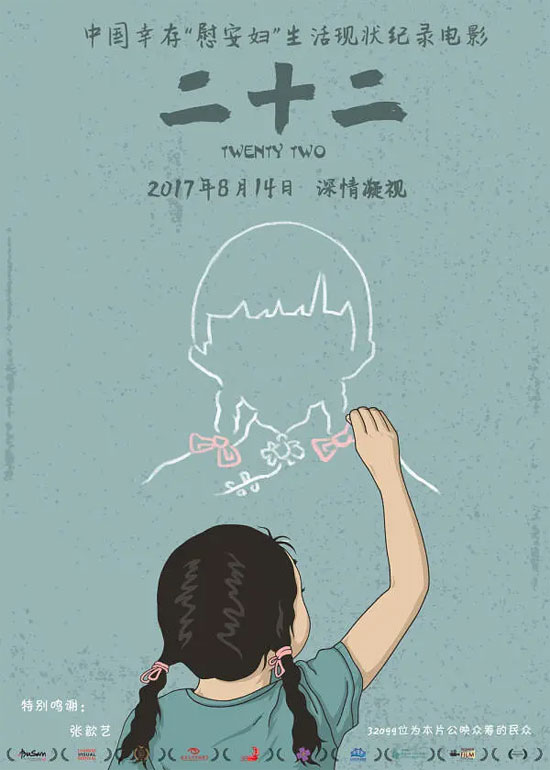

Film Name:二十二 / Twenty Two / 22

This film doesn’t need overly flowery or grandiose titles—simple and pure will do.

Long before August 14th, recommendations for the film “Twenty Two” had been pouring in. Both emotionally and logically, I felt I should go see it in theaters.

As the first documentary on the “comfort women” issue to receive a theatrical release, “Twenty Two” holds extraordinary significance. In a sense, supporting it—whether through box office attendance or vocal advocacy—could be seen as a form of “political correctness.” Yet, contrary to the prevailing sentiment, there are also many voices opposing or dismissing the film, citing various reasons: that “exposing old wounds” reveals “impure motives,” the subject matter being too heavy to bear, labeling it a “rescue mission” smacks of hysteria, or simply having “no interest” in such topics.

These are all impressions one might “anticipate” before watching the film. How well it’s actually made can only be known after viewing it.

“Comfort women”—a term we often instinctively avoid in daily life—is the film’s central theme.

Frankly, viewed purely as a documentary, this film falls short—even fails. Its primary flaw lies in its lack of compelling narrative drive. The content feels fragmented, filled with lengthy segments of elderly subjects’ daily routines and excessive “unnecessary” filler. In a conventional documentary, such elements might constitute 10% of the runtime at most; here, they occupy nearly half, prompting some impatient viewers to walk out midway…

Logically, we should have seen extensive coverage of the comfort women’s harrowing experiences and exposés of the Japanese Imperial Army’s heinous crimes during the invasion of China. It would have been even better if it had reflected the oppression of women by the old society’s powerful forces, the harm inflicted on victims by the surrounding world’s judgmental gaze, and the lack of genuine, effective support and assistance. —Yet upon viewing, one discovers the film contains surprisingly little substantive content. Even when the elderly women approach pivotal moments in their narratives, they abruptly cut themselves off with phrases like “No more, no more” or “I won’t say it, I won’t say it.” The “bitter secrets” the audience craves to uncover remain largely concealed.

Rather than living up to its “touted” central theme, the film offers very little genuinely valuable material (or “substance”). The fragmented and disjointed interview segments also contribute to a poor viewing experience…

Does all this mean the film is bad? Yes, it is—but this “badness” is precisely its “goodness.”

As director Guo Ke put it: “When you treat these elderly women as family, your filming gains restraint, and your questions find boundaries.”

Many people’s subconscious resistance to the “comfort women” subject stems from fear of causing secondary trauma to these survivors. Guo Ke clearly faced this challenge during filming, yet his solution is evident in the final product: refrain from digging deeper.

Therefore, rather than framing this documentary as about “comfort women,” it’s more accurate to see it as about a group of grandmothers. They appear no different from the elderly women we encounter in daily life, except that they happen to carry a tragic memory…

Yet this approach delivers an impact no less powerful than a raw, graphic depiction. On the contrary, the film provokes reflection on another level—our attitude toward life.

From “Thirty-Two” to “Twenty-Two,” the film interviews numerous elderly women who were forced into sexual slavery. The vast majority were born in the “1920s,” meaning most were under 20 when they endured their suffering…

We cannot fathom what they endured. We were not there. They have every reason to be heartbroken, angry, and despairing. Yet beyond their tears and desolation, we also glimpse another side of these elderly women.

Mao Yinmei, from South Korea, was deceived by the Japanese and imprisoned in a comfort station in China. To this day, she still remembers the phrase “Welcome” repeated countless times back then. That phrase, “Yilai Xiayi,” holds no warmth or comfort now—only a piercing, heart-wrenching sting…

But Mao Yinmei was not defeated by those years; she survived.

She still sings “Arirang” and “Ballad of the Bellflower,” the folk songs of her homeland. After liberation, she changed her original name “Park Cha-soon” to “Mao Yinmei,” taking the surname of her revered Chairman Mao. She no longer wished to revisit her unfamiliar hometown, for now she had caring relatives and friends by her side who cherished her.

Beyond being a “victim,” the elderly Lin Ailan also carried the identity of a “resister.” She was a heroic anti-Japanese fighter who proved herself equal to any man. She joined the guerrilla forces, stole Japanese ammunition, and even killed two Japanese soldiers. Yet her resistance left her infertile for life and afflicted with an incurable leg ailment.

This fiercely independent woman from childhood refused to be broken. She survived.

Even living alone in the nursing home, Lin Ailan couldn’t shake her “short temper.” She kept a knife by her bedside “to guard against thieves.” The commemorative medal awarded by the government for the 60th anniversary of the victory in the War of Resistance was her most cherished possession. When she couldn’t find it for a moment and mistakenly thought it had been stolen, she could make everyone around her feel utterly defeated.

When the nightmare struck, 17-year-old Li Ailian was seized by Japanese troops sweeping through her village. They dragged her to a neighboring house where she was raped, then taken to their base… She was forced into a comfort station twice.

Yet these horrors did not destroy Li Ailian; she survived.

When a neighbor’s cat gave birth to a litter of kittens left unattended, one found its way to her home. She fed it, and soon one became many. Her family says she spares no expense on food for herself, always letting the kittens eat first before she eats. In daily life, she remains a gentle, kind-hearted grandmother who cherishes all living things.

…………

Now, these surviving elders are passing away one after another. Early in the film, a young woman who had long visited and comforted the elderly wept as she shared that a grandmother she knew had died. At the time, her tear-stained face did not move me.

It wasn’t until near the end of the film, when she mentioned showing the grandmother photos of Japanese veterans, that we learned her other identity: Mai Yoneda, a Japanese exchange student who had volunteered for five years visiting surviving comfort women in Hainan. The grandmother had smiled and remarked, “The Japanese men are old now, their beards gone. They used to have beards…” She also mentioned that the grandmother harbored no extra hatred toward the Japanese or anyone else…

Her initial feelings of guilt and sympathy toward the elderly women gradually transformed into admiration and profound emotion. For even without this external attention and support, these women persisted in striving to live well.

Mao Yinmei, Lin Ailan, Li Ailian, Wei Shaolan… These elderly women, who once endured the horrors of being forced into sexual slavery, cannot forget that chapter of history. Were it not for that history, we likely would never have known them—yet clearly, that history does not define their entire lives. Neither hatred, fear, nor despair has crushed them. They persist in living their lives with heartfelt brilliance.

The film begins with the burial of Elder Chen Lintao and concludes with the burial of Elder Zhang Gaixiong.

Both funerals held in Shanxi seemed strikingly similar, forming a poignant echo… After the elders were laid to rest, the white snow and yellow earth gradually gave way to mountains cloaked in green—through the cycles of cold and heat, spring and autumn, each of us inevitably returns to dust. Before life ends, what mindset should we adopt to live our days?

“Forgetting the past means betrayal.” We must carry our “past” forward—a burden we cannot forget nor cast aside. As for how to face tomorrow, the elders offered their answer: remembrance and living.

When the lights came up at the film’s end, no one rose immediately. Nearly everyone remained seated—a proportion far greater than those waiting for post-credits scenes at Marvel movies… Throughout the screening, the theater remained profoundly quiet, as if any extraneous sound felt frivolous and intrusive.

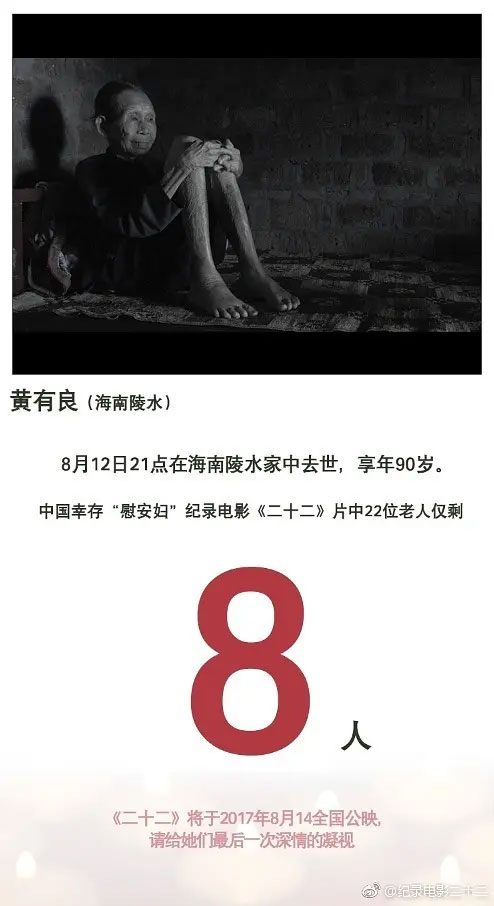

On the eve of “Twenty Two” premiering, the film’s official Weibo account posted a message: ’22’ transformed into “8.”

Sooner or later, this number will become “0.”

The question isn’t just how long that day is away, but whether we’ll still be able to remember sufficiently by then.

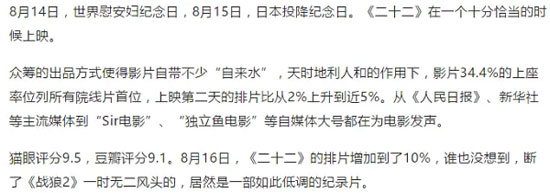

It’s heartening that, contrary to the dwindling countdown, “Twenty Two” is gaining traction in theaters. Its screening share climbed from under 2% on opening day to 5% on day two, reaching 10% on its third day, with box office earnings surpassing 40 million yuan.

Interestingly, this “comeback” has left the film’s promoters with mixed feelings. They worry that “Twenty Two” might be treated as a short-lived product for national sentiment, when it’s better suited for a steady, long-term approach.

Finally, I’d like to share my personal perspective on “Twenty Two.” It cannot bear the weight of excessive fervor; it is neither a rallying cry nor a battle hymn. Nor does it delve into profound criticism, deep reflection, or critical discourse. It hasn’t achieved this, nor can it—and frankly, it doesn’t aspire to. Let’s not force onto this film the “significance we think it should have”… We should be grateful it made it to theaters at all—why burden it with the weight of a thousand-pound banner?

“Twenty Two” may lack grand scope and fall short as a documentary, but it possesses a heart of gold.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Twenty Two 二十二 2015 Film Review: Remember, live well.