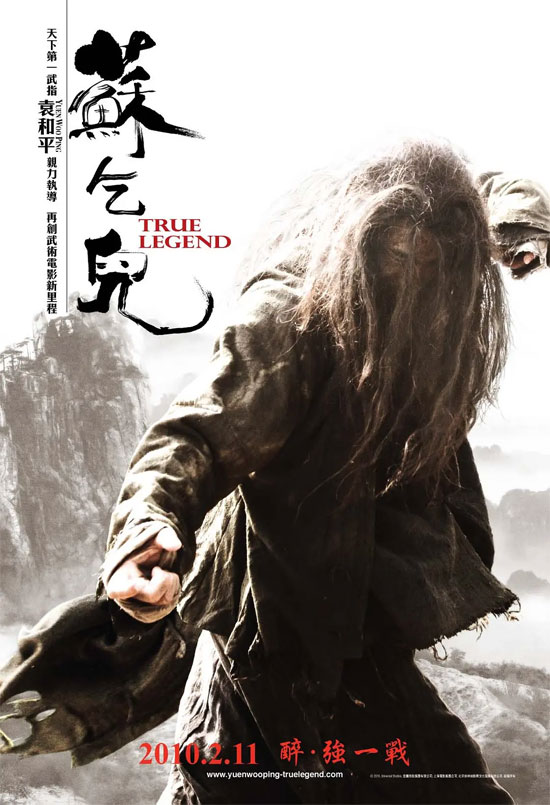

Film Name: 苏乞儿 / True Legend / Su Qi-Er / Beggar Su / 蘇乞兒

Jackie Chan’s classic song “Drunken Fist” radiates unbridled vigor: “Fear not the intoxication—cross seas vast and skies high. Be wild, be mad, be drunk in this very day.” These few lines ignite the blood while capturing the carefree spirit and swagger of drunken boxing. Since the late 1970s, when Yuen Woo-ping and Jackie Chan collaborated on the film “Drunken Master,” sparking a wave of kung fu comedies, the drunken boxing genre has remained a perennial favorite in the film industry. Yuen Woo-ping alone has repeatedly brought this unconventional martial art to the big screen. True Legend marks his first independent directorial effort since returning from Hollywood, with the signature drunken boxing sequences—his signature specialty—taking center stage, making it a particularly significant project.

Unfortunately, despite the legendary “Kung Fu Master” proclaiming to the media how he successfully blended trendy street dance elements with traditional drunken boxing, and boldly designing a 20-minute 3D sequence, it couldn’t mask the film’s lackluster and disappointing state.

Both “True Legend” and ‘Fearless’ were written by Du Zhilang. Whether this talented screenwriter grew weary or ran out of ideas after “Crime and Punishment” is unclear, but the resulting kung fu films share strikingly similar plots. In fact, if Su Qier had switched to practicing the Mysterious Shadow Fist, he could have easily opened his own Jingwu Academy. The story’s climax should have ended with Su Qier killing Yuan Lie. Yet the film inexplicably sends the Southern Kung Fu master wandering all the way to Heilongjiang for winter, where he moonlights as a foreign strongman fighter. This tacked-on subplot feels forced, as if the filmmakers were desperately trying to mold Su Qier into a national hero.

Historically, Huo Yuanjia did defeat strongmen, but legends about Su Qier revolve around martial arts rivalries. It’s entirely possible the old man never even saw a foreigner in his lifetime (except for Buddha statues in temples). While films aren’t history, this plot device of a thousand-mile journey to fight foreigners is genuinely hard to swallow. Su Qier’s most legendary aspect lies in his personal journey from despair to redemption, while Huo Yuanjia’s brilliance shone in resolving international conflicts. Yet now, “True Legend” appears to be merely “Fearless” in new packaging—lacking originality.

Of course, kung fu films ultimately rely on their fight scenes to speak for themselves; dwelling excessively on dramatic subplots adds little value. Compared to Yuen Woo-ping’s earlier works, “True Legend” adopts one of the rarest pure, unadulterated styles of martial arts. As the saying goes, “In the realm of martial arts, nothing is unbreakable except for speed.” The fight choreography in this film serves as the ultimate testament to this martial truth. The battle between Su Qier and his imaginary foe, the Martial God, emphasizes the element of “speed.” Due to his superior velocity, the Martial God consistently gains the upper hand between moves. This principle holds true for the pivotal street dance-inspired Drunken Fist sequence that follows.

Here’s an interesting aside: Master Yip had previously designed Drunken Fist styles for martial arts icons like Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and Donnie Yen—each with distinct flair. Jackie Chan’s version embraces a folksy, comedic approach, using drunken postures to numb pain and confuse opponents—akin to street-smart acrobatics. Jet Li’s Drunken Fist was unmatched in ferocity, unleashing latent power through intoxication; Donnie Yen’s version featured fluid, elegant somersaults, embodying the carefree spirit of “a drunken escape from sorrow.” As for Zhao Wenzhuo’s street dance take on Drunken Fist, it felt more like an emotional outburst fueled by drunkenness—to put it bluntly, drunken antics. The brawls against foreign strongmen are brutal, with fierce kicks and dominant moves—almost “hand-to-hand combat” in intensity. While this design greatly enhances the visual thrill, it also means most main characters’ kung fu leans heavily toward brute force, lacking variety and agility, which feels somewhat monotonous.

In Eastern literature and art, drunkards and beggars are rarely symbols of decadence. These figures often embody a world-weary wisdom and a detached, philosophical outlook. They live freely, unconstrained by convention, yet possess profound, enigmatic skills. Su Qier epitomizes this unconventional knight-errant archetype. Yet in Eight Master’s “True Legend,” the dramatic scenes are carbon copies of “Fearless,” failing to explore Su Can’s inner journey. While the martial arts sequences deliver raw power and spectacle, they too feel monotonous and rigid. Consequently, he falls short of crafting an ideal Su Qier that resonates with audiences. Old wine in a new bottle—even if Liu Ling were reborn, he’d likely find himself sobering up.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » True Legend 2010 Film Review: New bottle, old wine; the intoxication lingers.