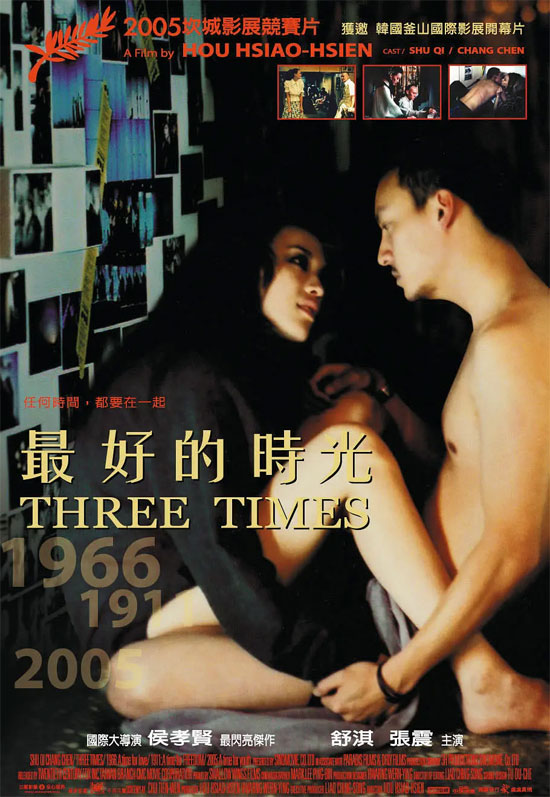

Film Name: 最好的时光 / Three Times / 最好的時光

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s new film, The Best of Times, is three dreams. A dream of love, a dream of freedom, a dream of youth. Shu Qi and Chang Chen portray three love stories within these dreams, spanning a century.

The first dream, the dream of love, 1966.

Hou Hsiao-hsien calls this a recollection of his own youthful days. Zhen (Chang Chen), a teenager who failed his university entrance exams and is about to enlist, meets Xiu Mei (Shu Qi), a pool hall attendant, in a humble billiard hall in rural Kaohsiung. (It seems that back then, Taiwanese billiard halls often employed such female attendants who played alongside customers, somewhat akin to betel nut girls, serving to attract patrons.) Ah-Chen frequently visited that pool hall and had even written letters to a previous attendant who worked there before Shu Qi. She casually tossed his letters into a drawer. On the eve of his departure for military service in the north, he came looking for her, only to find she had left. So he played pool with Xiu Mei instead. Here begins one of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s signature extended takes. They played in silence, exchanging not even a glance. Yet one could almost hear their hearts trembling. Later, Ah-Chen wrote Xiu-Mei a few brief lines. Then, on a day off, he sought her out only to find she had vanished. He searched relentlessly, feeling as if he’d traversed all of southern Taiwan in half a day. Finally, at dusk, he found her. When they met, they said little, only laughed. Laughed until they bent over. They ate noodles at a street stall, then waited at the bus stop for a northbound bus. He had to return to camp before nine the next morning. Here, Hou employs an extreme close-up rarely seen in his films: two hands. A-Chen’s hand hesitantly, tentatively approached Xiu-Mei’s, slowly clasping hers, then interlocking their fingers. Hand in hand, awkwardly, they stood beneath the streetlight in the drizzling night. A-Chen held the umbrella, leaving half of Xiu-Mei exposed to the rain. The old English song “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” drifted like smoke, and the story ended.

What happened next? Did they fall in love? Get married? Find happiness? Audiences might ask such mundane questions. But none of that truly matters. That single moment of their fingers intertwined was life’s finest hour. No matter how long and gray the years ahead, looking back, it will always shine like a diamond. Every heart, buried deep in dust, remembers such a moment, doesn’t it?

The Second Dream: The Dream of Freedom, 1911.

This story carries a sense of historical sentiment. Shu Qi plays a courtesan, while Chang Chen portrays a scholar (who is essentially a client, though such bluntness would be an insult to propriety). It is said that due to concerns about actors struggling with the mixed classical Chinese and Japanese dialogue, the film was simply rendered as a silent picture. The dialogue appears on a backdrop resembling golden embroidery, creating a classical and luxurious effect. The entire narrative unfolds through several nights Zhang Zhen spends with Shu Qi. On screen, their fingertips never touch. She silently attends to his ablutions; he silently watches her play and sing. Seated at her dressing table, she converses with him behind her without turning. Working for Liang Qichao, he frequently travels north, to Japan, or the mainland. He writes her letters, lamenting the state of the times. Clearly, he regarded her as his soulmate. It reminds me of what someone once said: ancient love often blossomed in brothels.

He was a man of contradictions. He published articles opposing concubinage in newspapers, yet spent a hundred taels of silver to redeem “Ah Mei” from servitude only to make her another man’s concubine. He frequented courtesans, clearly loving her, yet unwilling or afraid to consider her future. (In vulgar modern terms: unwilling to take responsibility for her.) His contradictions bred her sorrowful uncertainty about her status as a concubine. Before his departure, she suppressed her grief and walked to the window. Without looking at him, she asked: “Have you ever considered my future?” He lowered his head, silent.

After he left, the Wuchang Uprising erupted. He wrote her letters brimming with scholarly idealism. She merely traced his letters with her fingertips, their profound tenderness deeply moving. My God, she truly loved him so deeply. The story ends. Her status as a concubine remains unresolved.

The third dream, a dream of youth, 2005.

I dislike this dream. It inherits the style of “Millennium Mambo.” Motorcycles, pubs, drugs, electronic music, homosexuality, promiscuity. Modern elements are chaotically woven into a tale of tangled love. Is there love? Or just sex? Or perhaps, just confusion? The only scene I cherish is Chang Chen riding his motorcycle with Shu Qi leaning her face against his shoulder. Her eyes, perpetually hollow and despondent, seemed to gain substance in that moment. It felt like genuine love. Even if it was an illusion. Is this the youth of this generation?

The letter exchanges in the first two stories evolve here into text messages and online comments. Classical romance dissolves like this. So what about love? Is it still there?

This story feels like a satire on modern love. The first tale was genuinely beautiful. The second contained heart-wrenching tenderness. But by this point, I see no beauty, let alone love.

Overall: Shu Qi’s performance is truly excellent. In the first story, opposite Chang Chen, she is awkward, giggling nervously, stealing glances at him—her eyes brimming with profound affection. On the ferry, as the river breeze ruffles her hair, her expression reveals a secret joy from the depths of her soul, too private to share with others yet palpable to the audience. In the second story, her hair is swept up high, clad in wide-sleeved robes, perfectly embodying gentle refinement. Her deep affection remained hidden. In the third story, as a decadent modern woman, she smoked with a hungry intensity, her eyes outlined in deep black circles. Three eras, three entirely different types of women, were brought to life within her alone. Her Golden Horse Award was well-deserved. In comparison, Chang Chen’s performance felt slightly thinner. Personally, I loved his look in the second story—his lean face was handsome and had an intellectual air.

As for the director, Hou Hsiao-hsien has explored all three story types before. Simply put, this film is roughly equivalent to “Dust in the Wind” + “Flowers of Shanghai” + “Millennium Mambo.” There’s no major breakthrough in his directorial approach. Yet I still adore it. Especially the first segment. Especially that close-up of their clasped hands. It’s cliché, yet I still wept. Within it lies the director’s youth, my own youth, and I believe the youth of countless others.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Three Times 2005 Film Review: Memories that last forever are the best times.