Film Name: 戲台 / The Stage

It’s been ages since I last heard the sound of pigeon whistles in Beijing in a film or TV production. When that sound came through at the beginning of “The Stage,” I knew that something long-lost had returned.

Chen Peisi is a symbol of laughter and quality for people of our generation. Though he’s stepped back from the mainstream spotlight in recent years, he’s never stopped creating and performing. This film adaptation of the play of the same name once again proves that he’s still got it.

Of course, I must admit that “The Stage” is a bit too old-fashioned and pure in both its substance and appearance, leaning more toward the stage and performance. In today’s market, it lacks a strong “cinematic feel,” and if it were aimed at the general audience, it might not be very appealing… But for those who enjoy this style, it’s excellent.

The “Chen Xia’er” of yesteryear is now nearly the same age as Chen Qiang in his later years, so there’s no need to chase trends. Doing what one does best is the right path.

[Friendly reminder: The following text contains spoilers.]

The story of “The Stage” is simple: the Wuqing Troupe brings a group of renowned actors to perform at the Grand Theater. Coincidentally, Hong Dashi, who has just entered Beijing, is causing trouble at the theater and specifically requests that his fellow villager, the loud-voiced singer, perform ” Farewell My Concubine.” Faced with the threat of losing their lives on one side and the risk of damaging their reputation on the other, Hou, the troupe leader, and Wu, the manager, had no choice but to improvise and survive in the midst of chaos. How this grand performance would ultimately unfold was anyone’s guess.

The film’s content can be interpreted in several ways, such as the chaos in the entertainment industry or the integrity of art. Personally, I lean toward “the different attitudes and influences of the environment on artistic creation.” Below, I will select a few representative characters and discuss them under three categories: destroyers, chaos-makers, and defenders.

First, the destroyers: Xu Mingli and Hong Dashuai.

Xu Mingli is a classic fence-sitter and opportunist. No matter who takes control of the capital, he can immediately don their uniform and play their military anthem. Thus, no matter how the political landscape shifts, he can maintain his position as Director of the Education Bureau, as everyone finds him useful.

Unlike the theater-illiterate General Hong, Xu Mingli understands theater. He is well aware that the general is acting on a whim and behaving recklessly, yet he not only fails to offer any warnings but instead goes along with it, even going further to overhaul the theater troupe.

People like Xu Mingli have no reverence or compassion for artistic creation. As long as it can serve as a tool for flattery, he can immediately force the theater to hold private performances, have Liu Bang hang himself, and in the process, satisfy his own lust for power through the power of others.

While both destroy trees, if Xu Mingli is like pruning branches, peeling bark, and pouring hot water—a subtle form of destruction—then General Hong is like a whirlwind uprooting the tree entirely.

This brute knows nothing about theater. He impulsively summoned his men to the Dexiang Grand Theater to watch a play simply because he caught a glimpse of the theater’s grandeur and heard a passing mention from the Sixth Concubine. In his excitement, he even insisted on going incognito.

Such an outsider causing trouble backstage would normally be immediately kicked out or given a good scolding, but Hong Dashuai was the one in charge in Beijing at the time, holding a gun symbolizing power. Even if he couldn’t hold that position for a day (he entered the city in the morning and was driven out by Lan Dashuai in the evening)—the most typical example was the brutal death of the local tyrant Liu Ba Ye. His judgment was correct, Hong Dashi’s reign would not last long, but even if it only lasted half a day, Hong Dashi could still destroy him without regard for martial ethics.

Relying on his gun to cause trouble on and off the stage, the key point is that Hong Dashi was not a “villain with malicious intent,” but rather a “fool with a sudden idea.” His sudden actions were enough to form a complete set of martial arts moves, so one can imagine the extent of the damage he caused to the entire opera ecosystem.

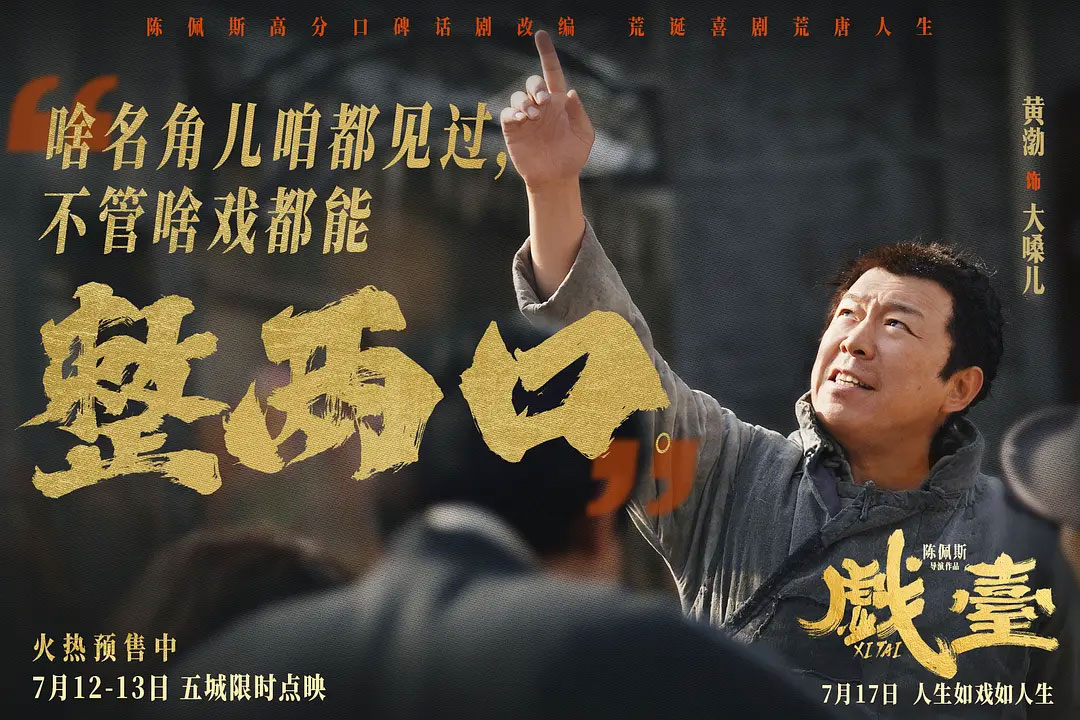

Next came the more complex chaos-makers. Emotionally, they were defenders of the arts, but objectively, they also played a destructive role, such as the loudmouth from the dumpling shop.

As a seasoned theater enthusiast who loves to frequent the theater and a distracted employee at a dumpling shop, Dàzǎng’ér’s spiritual haven naturally lies in the small space between the theater troupe and the stage. From this perspective, he certainly wouldn’t want his beloved opera to be ruined.

At the same time, Dasao is a big talker who loves to boast and joke around. He can offer sharp commentary on any matter, and his greatest pride likely comes from encountering newcomers like Hong Dasao, allowing him to freely educate and show off as a “professional,” with opera serving as his capital for boasting.

However, Dasao’s half-baked knowledge and misleading nonsense inadvertently became a guide for Hong Dashuai’s self-righteousness and chaos in the theater. Later, he ended up making a mess of things on and off stage, playing the role of a terrible Chu Bawang. This shows that even chaos can sometimes lead to evil.

The more controversial chaotic character is the Sixth Concubine Siyue. Many viewers felt that this role was poorly designed and that her scenes were unnecessary, but they overlooked the fact that her existence served as a critical supplement and enrichment to the film.

On the surface, Si Yue’s character is somewhat similar to Da Zao’er, both being theater enthusiasts who elevate their admiration for the renowned actor Jin Xiaotian to their highest spiritual pursuit. However, due to her abnormal obsession and blind obedience toward Jin Xiaotian, she inadvertently encourages him to consume more opium.

However, beyond being a clumsy supporter and blind destroyer, Si Yue, as the only female character in “The Stage,” shares the “victim” status with the theater troupe—the film hints that Hong Dasao controls her through opium. Her status allows her to enjoy luxury and wealth, yet she cannot distinguish between Jin Xiaotian and Dazhao when they are made up, suggesting she is not truly knowledgeable about theater… All of this reflects how barren and numb Si Yue’s spiritual world is.

Later, Si Yue is willing to sacrifice everything and even decides to elope with Jin Xiaotian, which is her desperate attempt to cling to a lifeline. She doesn’t know if the elopement will succeed or what will happen if she’s caught by the general. In a time of chaos, life is as fleeting as a floating reed; if she can live for herself for even a moment, she will.

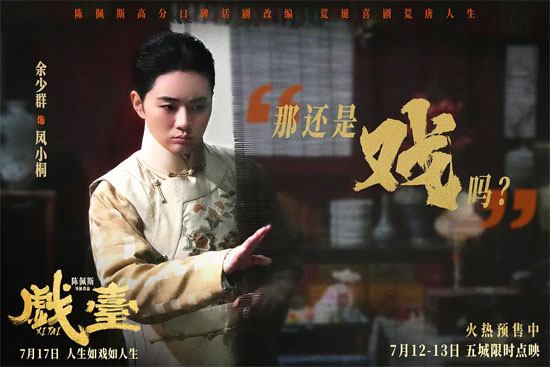

Finally, looking at the defenders is much simpler, such as the most popular character Feng Xiaotong.

Mr. Feng is likable because he is the most passionate and pure-hearted person in “The Stage.” Although Hou Xiting is more experienced, he cannot help but be tainted by worldliness. Jin Xiaotian is a master of opera, but his private life is a mess… Moreover, Feng Xiaotong also has a touch of Cheng Dieyi’s “merging of self and role.” He is infatuated with his third brother and becomes distraught when he sees him sleeping with a wild woman.

Such a pure and earnest person naturally suffers the most in the chaos of the “General’s Theater.” Before performing, he must fend off soldiers who try to assault him; during the performance, he must endure the amateurish shouting of others. It is only when Jin Xiaotian returns to the stage to sing “The Conqueror” that he finally shows the smile he deserves.

Unfortunately, the Blue General who entered the city later preferred male dan roles, and Feng Xiaotong, unable to endure the humiliation, chose to jump into the river and commit suicide. His resolute and fierce determination, akin to that of Yu Ji, is an indispensable virtue for an artist defending artistic creation.

In contrast, Hou Xiting is more “murky” and has taken the most difficult path.

“The Stage” focuses more on Hong Dashuai, the loud-voiced amateur, Jin Xiaotian, and others. At first glance, Hou Xiting, the leader of the Wuxing Troupe, seems somewhat peripheral, and his character is similar to that of Wu Manager of the theater, both being versatile individuals.

However, in reality, Hou Xiting is the soul and backbone of the entire troupe. If one performer cannot take the stage, another can step in and perform, but if he were to leave, the entire troupe would disband… To preserve the troupe’s reputation, he must save Jin Xiaotian, who is nearly dead from opium addiction. To protect the lives of everyone in the troupe, he must humble himself and accommodate Hong Dashuai’s caprices.

Hou Xiting is indeed more cunning and spineless than Feng Xiaotong, but he is not as endlessly accommodating as Manager Wu. When Jin Xiaotian and Feng Xiaotong defied the general’s anger and performed the original version of “Farewell My Concubine” on stage, he would also risk everything to accompany them personally, demonstrating at least some integrity.

I think this is one of the reasons why many forms of artistic creation and expression have endured to this day—they possess a backbone without being rigidly inflexible, but rather capable of both yielding and standing firm.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Stage 戲台 2025 Film Review: That’s really authentic!