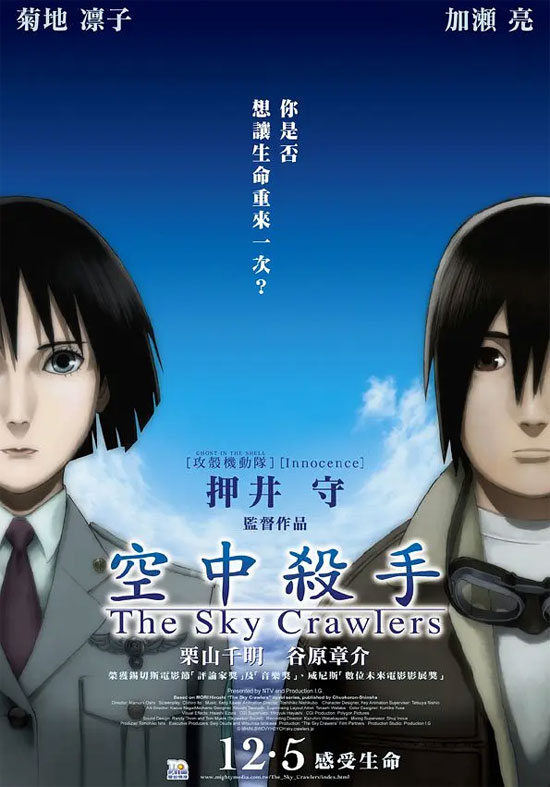

Film Name: 空中杀手 / The Sky Crawlers / スカイ・クロラ

I. The Film’s Motivation

As director Mamoru Oshii himself stated: “Without motivation, a film won’t move.” If we view The Sky Crawlers itself as “a fighter plane,” then the engine enabling its takeoff and combat is precisely the film’s creative motivation—the fundamental aspect we must first understand.

The film’s origins can be simply summarized in two points: First, Director Oshii had long desired to create an animated film centered on fighter planes and aerial combat. While aircraft and flight techniques were frequently depicted in Hayao Miyazaki’s films, Oshii believed he “would never be inferior to Miyazaki in depicting aerial combat.” He even possessed the confidence to call himself “Japan’s foremost director of aerial combat films.” Second, in 2005, upon a friend’s recommendation, Director Oshii read Mori Hiroshi’s novel of the same name and was profoundly moved. Just as Director Kon decided to adapt Tsutsui Yasutaka’s novel into “Paprika,” Oshii felt an impulse to create an animated film based on this novel.

Two aspects of the novel particularly captivated him: First, the world depicted as a “future peaceful society where war exists solely as a commercial activity—an ‘entertainment program’ produced for people’s leisure after meals.” Second, the participants in these wars—individuals ‘manufactured’ through genetic technology, who never age or die except in battle. These “eternal children” possess adult bodies yet retain the youthful faces of 16- or 17-year-olds forever. What kind of world is this? What kind of lives do these “eternal children” lead? In other words, the former is the novel’s worldview, and the latter is the protagonists’ outlook on life. At the first planning meeting, Director Oshii discussed how to effectively visualize these two points, stating they were “the key to the film’s success.”

However, at this point, Oshii only felt a strong impulse to adapt “The Sky Crawlers” into a film. Though this impulse was intense, he hadn’t yet made a final decision. What ultimately sealed his resolve was a dinner on July 5, 2005, when he reunited with his long-separated daughter. When he showed her the project memo, she exclaimed, “This is such an interesting story!” Another reason for his hesitation was uncertainty about the approach: should he express the novel through his familiar sci-fi lens, or through a more ordinary, realistic portrayal of life? His daughter provided the answer to this question as well, supporting the latter approach.

From that day onward, Oshii’s resolve seemed to solidify instantly. He told those around him, “I’ve always made animation for myself. This time, I want to make an animation for young people.” This was the moment Oshii found his motivation to make this film.

II. The Film’s Transcendence

1. Realistic Science Fiction

The use of everyday props from our present-day lives to depict science fiction represents a departure from Oshii’s previous sci-fi works in “The Sky Crawlers.”

In truth, both the “Children of Eternity” and commercialized warfare retain a sci-fi essence in their conceptual design. Yet Oshii deliberately sets the film in a world parallel to our own, where jet-powered aircraft are absent—only propeller-driven planes exist. The film’s backgrounds were shot in Ireland and Poland—the first half in Ireland, the latter half in Poland.

One could say this is “science fiction diluted by reality,” an impure form of sci-fi. Yet by stripping away the genre’s flashy trappings, Oshii achieves a more precise capture of character psychology and a more nuanced grasp of human emotion. This eliminates the mechanical detachment present in some of his earlier works, replacing it with a more direct immersion in the film’s ethereal, profound worldview and philosophy of life.

To achieve this grounded sci-fi, Oshii made an exception by not writing the script himself. Instead, he invited 23-year-old screenwriter Itō, known for the romantic film “Spring Snow,” to pen the story. Oshii presented Ito with three key points he wanted clearly expressed in the script: First, is it truly necessary for people to become adults? Second, the depiction of war and the era. Third, true human love—the terrifying aspects of love. The first two points “closely align with the original novel’s worldview and values,” while the third reflects “Oshii’s own perspective on love.”

2. Creating for the Young

Throughout his career, Oshii’s mainstream works have been “aimed at adult audiences.” Yet, as detailed in the section on motivation, this film represents “Oshii creating for the young.” This conviction was “strong and remained constant throughout the entire creative process.”

In his director’s statement, Oshii wrote[1]:

The theme of this film is the heartfelt cry of children living in twilight times—what is “life,” what is “death”? We who exist in the modern age, living in material abundance yet lacking in manners, surrounded by countless objects and information, and with the possibility of eternal life through genetic technology—how should we live out this slow-moving lifetime?

The answer to this question lies not with us adults, but with the young people who will inhabit the future—those perpetually searching for meaning in existence, bewildered by the hollow words of adults, and compelled to survive in a chaotic future. They are the “eternal children” who possess infinite time.

······

Through this film, I wish to convey to these young people surviving in a cruel era: unless one contemplates death, the fullness of life can never be attained.

The film’s most profound revelation lies in showing that those who gain eternal life actually yearn most for death. Thus they fight. For the “Children of Eternity,” combat holds two meanings: one is an escape from life, the other a pursuit of life. Escaping life means that when they grow increasingly lost about the value of their existence, battle becomes a crevice where they can temporarily hide—a place where they need not confront that confusion. Pursuing life means that when they realize death’s crucial significance to existence, battle becomes their sole means of obtaining death, which in turn grants them the opportunity to attain true life.

From the outset, the film permeates an eerie atmosphere: the origins of the “Eternal Children” begin to unfold when the deceased Yumegawa Aizu—who always “neatly folds newspapers”—reappears at the base. Yet at this stage, protagonist Minami Yuichi remains unaware that these “Eternal Children” are merely “human-made clones” capable of being replicated identically even after death. The most memorable scene in the film is when Yagi, who has feelings for Yuichi, sees that Yuichi truly loves Kusanagi Motoko and reveals the truth about the “Eternal Child” to him. The memories of the “Eternal Child” were all pre-programmed by humans. Yuichi possessed no genuine recollections of his past, which is why he fixated on any information concerning the “Eternal Child.” He frequently asked questions like, “Is he/she also an ‘Eternal Child’?” He was constantly searching for the answer to the mystery of the “Eternal Child”—in truth, his underlying desire was to find an answer that would allow him to stop feeling lost. Yet precisely when he learns the truth, he plunges into deeper disorientation.

At this moment, Suzu’s love awakens his heart. He resolves to defy his own mortality, thereby fulfilling the meaning of existence—that even as a manufactured being, even as an Eternal Child, life holds purpose. Finally, he utters a profound reflection on existence:

Even paths traversed countless times can lead to places never before trodden.

It is precisely because we have walked countless paths that the scenery transforms endlessly.

Is this not enough?

Is it not enough precisely because it is only this?

3. The Art and Technique of Aerial Combat

Depicting aerial combat has long been a desire of Oshii’s, and this time he has realized it. In his own words, the film The Sky Crawlers consists of seven parts story and three parts fighter planes. It is gratifying that he was able to achieve his vision of portraying aerial combat through such an unconventional worldview.

In the film, whether it’s the design of the fighter planes, the depiction of their movements, the skillful use of camera work during aerial combat, or the suffocating tension created by all these elements combined, Director Oshii lives up to his original confidence—this truly represents the pinnacle of aerial combat scenes in Japanese animation. Of course, such masterful execution wouldn’t have been possible without his two key collaborators: Atsushi Takeuchi, with his extensive mechanical design experience, who handled the mecha designs; and Hiroyuki Hayashi, with his deep expertise in 3D imaging, who served as the film’s CGI supervisor.

At this point, the author must emphasize the film’s unique blend of 3D and 2D animation. Initially, Oshii “wanted to shoot this animation using traditional 2D methods,” but he “quickly realized that achieving the level of aerial combat he envisioned was impossible for 2D animators alone,” necessitating the use of 3D technology. [2] 3D technology made the aerial combat more three-dimensional and closer to reality, allowing for meticulous depictions of the physical movements of environmental elements like clouds, fog, and water droplets. In fact, clouds held special significance in this film. The distinction between above and below the clouds represented not only the separation of sky and earth but, from a technical perspective, also the boundary between 3D and 2D. The scenes above the clouds were primarily rendered in 3D, while those below were mostly completed using traditional 2D techniques. Such extensive use of 3D technology was unprecedented in Oshii’s previous works, marking a clear transcendence of his earlier approaches.

III. Limitations of the Film

Director Oshii’s most defining trait lies in his relentless pursuit and unwavering faith in world-building. Unlike Miyazaki’s free-form imaginative approach, Oshii consistently dedicates extensive time to meticulously crafting and grounding his film’s universe. This worldview serves as the film’s backbone—without it, the narrative cannot stand. Oshii holds this conviction as absolute.

While a unified worldview indeed lends the film coherence and focus, the problem lies in the fact that a meticulously crafted world alone is insufficient to guarantee an animation’s success. The greatest strength of animation lies in imagination, which manifests most vividly in the movement and transformation of its subjects—not in the grandeur of its world-building or the depth of its narrative. Consider the ever-changing expressions and movements of Disney’s characters, or the fantastical imagery and scenarios in Miyazaki’s animations that transcend human common sense. Perhaps this helps us grasp what imagination truly means for animation.

Director Oshii’s works habitually delve deeply into world-building, yet fail to deliver the unique joy inherent in watching animation. In other words, viewing his animated films feels little different from watching live-action movies. Though his directorial skills rival any other filmmaker, his obsessions clearly belong more in the realm of live-action cinema.

For a long time, Oshii’s films underperformed at the box office. He reflected on why this happened, even collaborating with producer Toshio Suzuki—Hayao Miyazaki’s longtime partner—to plan new projects, but the results were underwhelming. Even works like The Sky Crawlers, which transcended many of Oshii’s previous creative experiences, still faced limitations he couldn’t overcome. Thus, in selecting themes for his new works, Oshii often gravitates toward those that are profoundly heavy, painfully profound, bitterly painful, and acridly bitter. These works embody the worldview he holds dear and believes in. In truth, it’s not that In this era of entertainment, fast-food culture, and leisure, it’s not that profound, heavy, painful, bitter, and sour works necessarily lack market appeal, nor is it that films made solely to pander to the public’s desire for entertainment, fast-food, and leisure are the only legitimate path. Rather, it’s that in selecting a film’s theme, one must at least consider the audience’s needs and not stubbornly persist in perpetuating a “university professor”-style discourse system.

Hayao Miyazaki’s earlier works also often featured large and profound themes, such as “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind” and “Princess Mononoke.” But unlike Director Oshii, Miyazaki’s approach to expressing these themes was highly accessible to the masses—he created a wealth of imaginative symbols and scenes, allowing audiences to absorb the film’s thematic messages while savoring the surreal delight of animation. In other words, Miyazaki devised a method for making profound themes accessible to the masses. Director Oshii, however, has yet to find a way to present his deep themes without causing audience fatigue—indeed, to make them willingly embraced.

As mentioned earlier, The Sky Crawlers is a work by director Mamoru Oshii as he approaches his sixtieth birthday. This signifies first and foremost that it is a mature work, and beyond that, we see numerous ways in which it surpasses Oshii’s previous films. Regardless, we look forward to Director Oshii offering audiences even more self-transcendence in his future works.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Sky Crawlers 2008 Animation Film Review: What has Mamoru Oshii surpassed and what has he not surpassed?