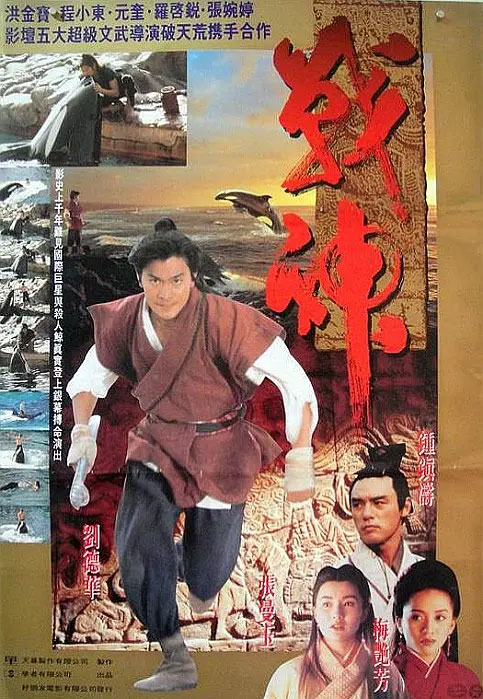

Film Name: 战神传说 / The Moon Warriors / Moon Warriors / 戰神傳說

The director of this film is Sammo Hung. Yes, that very Sammo Hung.

I first saw it thirteen years ago. Being rather young at the time, I only vaguely recall that dolphin that seemed to have travelled through time, and that rather lovely poem. After entering university, I watched it again on the campus network, and found it to be a completely different experience.

The plot devices are admittedly not particularly fresh: the genuine Crown Prince is persecuted by his treacherous younger brother and forced into exile. Thus the righteous flee while villains pursue, encountering the righteous yet indifferent youth Ah Fei along the way, all interwoven with a four-way love triangle involving two men and two women. Maggie plays the undercover maid Mo Xian’er (what a name…) stationed beside the prince. Like all melodramatic films, the infiltrator falls for her enemy, culminating in the utterly melodramatic sacrifice of her life in her lover’s arms. Finally, the forces of good and evil clash in a life-or-death battle within the underground imperial tomb, providing a spectacle for onlookers.

Of course, this isn’t all I wish to say, nor is it my assessment of the film. For the crux has only just begun: the ending. The ending redeems the film, preventing it from becoming mere chicken bones.

If one defines it as a “defend the king” film, then examining all such works—even the harrowing like Chang Cheh’s The Shanghai Thirteen—reveals an unspoken convention: the “king” being defended always survives, even if amidst a sea of corpses. But MARS is different. After all that effort, Crown Prince Yan Shisan still meets his end. This effectively renders the entire narrative a meaningless stalemate built upon initial misdirection—which, upon reflection, is rather intriguing. Everyone assumes the protected figure should ultimately bear the weight of others’ fearless sacrifices to become a righteous ruler, thereby perpetuating that justice and tradition. This ensures those selfless deaths retain their significance. Yet the survivor possesses no royal bloodline to inherit the throne; at best, he inherits Shrimp Tail Village. The only one who truly survives is Ah Fei.

It’s intriguing, yet rather cold. It’s not that numerous deaths equate to coldness, but rather that death here becomes mere posture and formality. He thinks not, holds no stance, no longer imbuing death with noble meaning or intricate purpose. Death is death. The moment the blade touches the chest, notions of good triumphing over evil, of right and wrong, dissolve utterly, leaving no room for interpretation.

Death is death. Grand ideals like the world order or righteous cause cannot halt death’s advance. Death is beyond the grasp of conviction, just as redemption through justice—that ideal transcending animal instinct—also eludes the control of belief.

Such is humanity’s limitation.

This is the differing view of the martial world held by those who wield the pen and those who wield the blade. The former are immersed in human desires, finding them unfathomably deep; the latter, seeing only the stark divide between life and death.

This is the difference between those who wield blades and those who wield pens. They halt killing with killing, life for life. Freed from many shackles, they spare themselves tedious, fussy chatter. Having witnessed so much within it, they harbour few unrealistic fantasies about the underworld.

When Ah Fei finally returned to the underground imperial tomb, he found it strewn with wildflowers.

This ending is profoundly romantic, not because death makes it so, but precisely because it can disregard death—refusing to beat its chest or weep bitterly over it—that it achieves such romance. The last time Andy Lau visited Shanghai, a reporter asked him which actress he most wished to collaborate with. He answered Maggie Cheung. Their most recent collaboration was precisely this film, The Moon Warriors, thirteen years prior.

A lonely white hare, darting east and west.

Clothes are never as good as new,

People are never as good as old.

Thirteen years on, we finally understand why this verse resonates so profoundly.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Moon Warriors 1992 Film Review: The lonely white hare, darting east and glancing west