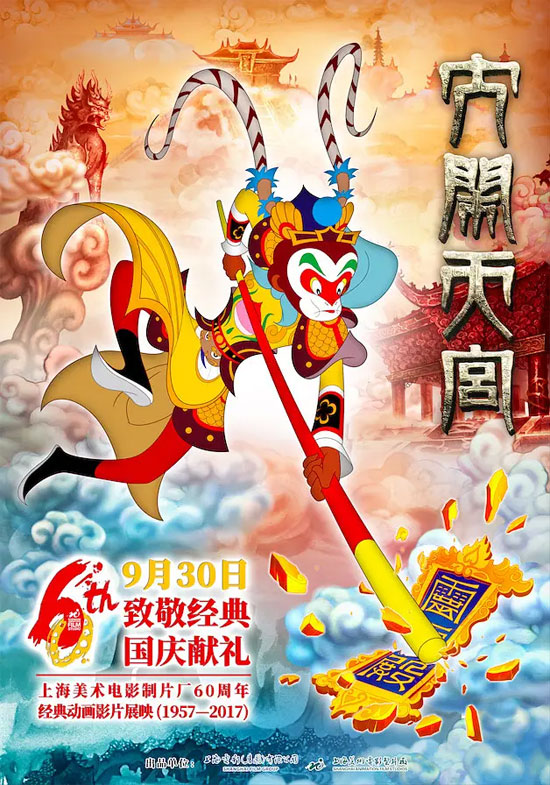

Film Name: 大闹天宫 / The Monkey King

One aspect of Chinese culture I particularly admire is its use of double meanings. On the surface, it speaks of one thing, but what it truly conveys is something else entirely. My favorite anti-gambling, anti-corruption TV series is called “Shi Ming.” Every character, every line of dialogue carries hidden subtext, making it deeply rewarding to savor. In contrast, its sequels “Shi Ming 2” and “Shi Ming 3” stripped away this nuanced meaning, making the viewing experience feel much blander. I recall a classic line from the Chinese political commissar in “Shi Ming”: “All along, I’ve been trying to figure out what he really meant by that.”

Any nation brimming with wisdom is, by nature, a rather exhausting place. Its people inevitably pay a price for this intellectual richness—the sheer fatigue of living. Nations populated by fools avoid this burden; with little to ponder or decipher, life remains effortless. China is different. We navigate an ocean of hidden meanings in daily existence. Why did our history witness literary inquisitions? Why did the Cultural Revolution suffocate so many? Because during these periods, the culture of subtext in Chinese society became grotesquely exaggerated, reaching unbearable levels.

Under such a culture, the emergence of Redology was inevitable. The classic status of The Dream of the Red Chamber stems largely from its subtext—its hidden meanings, its sayings that imply the opposite, its surface words that conceal underlying thoughts. Hongxue is the discipline dedicated to unearthing these layers. As one of the Four Great Classical Novels, Journey to the West possesses subtextual depth no less rich than The Dream of the Red Chamber. Why then is The Canonization of the Gods, another work of fantasy fiction, not counted among the Four Great Classics? Because its language is comparatively straightforward, its subtextual layers relatively sparse. Though it reads as “science fiction,” it lacks the depth and flavor. (Some friends question my use of “science fiction,” arguing such concepts didn’t exist then. In truth, my “science fiction” here refers to fantasy. Ancient “science fiction” was essentially superstition, heh.)

The textual value of “The Monkey King” stands as the pinnacle among Chinese animated adaptations, which is why its animated versions once enjoyed immense glory. Even its 3D adaptation still radiates a richly Chinese flavor. Not a single bit of this flavor comes from the so-called 3D effects. Thirty percent stems from its distinctly Chinese visual expression, while seventy percent comes from the text itself. Or rather, when watching “The Monkey King,” no matter how dazzling the 3D spectacle, I never linger on the lavishly rendered Heavenly Palace—a point that sets it apart from other animations.

Many animations, like some of Miyazaki’s works, focus on crafting an enchanting imaginary world that captivates viewers. Yet in “The Monkey King,” no matter how breathtakingly beautiful or imaginative the celestial realm may be, its allure lies not in the fantasy itself, but in the decadent, extravagant lifestyle of the bureaucratic class it represents. This underlying subtext makes it impossible to yearn for that world. This is the most powerful force of “The Monkey King.” While foreigners are still marveling, “Wow, how beautiful the Peach Garden is! How magnificent the Heavenly Palace is!” you, as an inheritor of Chinese culture, know full well that this is precisely what the film satirizes.

For instance, how did the celestial court’s attitude toward Sun Wukong evolve? This aspect alone makes the narrative compelling. Only two figures served as intermediaries between heaven and earth: Tai Bai Jin Xing and the Tower-bearing Li Tianwang. The former was a dove, advocating pacification—in modern terms, resolving issues through dialogue—while the latter was a quintessential hawk, believing force should settle everything. Initially, the Jade Emperor heeded Tai Bai Jin Xing’s counsel, coaxing Sun Wukong to the celestial court and granting him a minor official post to keep him in check. When this failed, the Jade Emperor dispatched heavenly troops to subdue him directly. After being defeated by Sun Wukong, the Jade Emperor summoned him again to view the Peach Garden. After Sun Wukong once again saw through the ruse and caused chaos at the Peach Banquet, the Jade Emperor, feeling humiliated, dispatched a hundred thousand celestial soldiers to eliminate Sun Wukong… This shift in tactics actually reflects a certain real-world political attitude shift, where leadership makes decisions by balancing the struggles between doves and hawks.

During Sun Wukong’s first visit to the Golden Hall, he taunted the generals flanking the throne. One blurted out, “The demon monkey is here!” Sun retorted with a laugh, “You… you… aren’t you supposed to be mute?” How bitingly ironic this line is! Barely having entered the heavenly court, he already laid bare the ugly realities of the bureaucratic world.

When Sun Wukong proclaimed himself the Great Sage Equal to Heaven, and the Tower-bearing Li Tianwang could no longer subdue him, Tai Bai Jinxing suggested, “Why not play along? Grant him the empty title of ‘Great Sage Equal to Heaven,’ keep him in heaven, and tame his wild nature.” The Jade Emperor hesitated, “It sounds good, but won’t he cause trouble again after a while?” Seizing the moment, the Heavenly King Li interjected, “To prevent future trouble, we must cut the grass at its roots!” The Jade Emperor glanced at the Heavenly King before turning to Tai Bai Jinxing: “Your strategy remains superior. Assign him to guard the Queen Mother’s Peach Garden to tame his wild nature. Should he cause trouble again, arrest him on the spot!” This passage is truly remarkable. How cunning of Tai Bai Jin Xing! While military officers wage war openly, civil officials often strike from behind. The Jade Emperor’s words are also thought-provoking. He first predicted the monkey would be difficult to manage and cause trouble over time, yet later advocated entrusting the Peach Garden to Sun Wukong. He clearly knew Sun Wukong was a monkey—and monkeys adore peaches. Why then entrust him with the Peach Garden? Did he expect Sun Wukong to guard the orchard without stealing a single peach? Or did he deliberately intend for Sun Wukong to steal the immortal peaches? The hidden meanings here are endless.

“The Monkey King,” indeed the entire “Journey to the West,” consistently exposes China’s bureaucratic culture. Both attempts to recruit Sun Wukong were exposed as frauds precisely because he clashed with this culture. That culture boils down to one word: “control.” When Ma Tianjun inspected the celestial horses, he boasted, ” I’m the one in charge of the heavenly horses—and your superior, you monkey!” When the Seven Fairies came to pick peaches, the Earth Deity couldn’t persuade them otherwise, and he too argued: “The Queen Mother’s peach orchard—we’ve come to pick peaches here. Why should he be in charge?” The core lies in that word “control,” yet Sun Wukong was the most resistant to it, the least willing to be controlled. He didn’t know how to manage subordinates, believing everyone equal—whether ruling Flower-Fruit Mountain or releasing celestial horses as Horse Keeper. Nor did he know how to treat superiors, refusing to play dumb or offer flattery.

These are just simple examples. “The Monkey King” is precisely such a work. Its powerful underlying text makes viewers see not just the film, but reflect on the metaphors behind these characters, plots, and dialogues. Its humor lies in the knowing smile that comes from understanding these deeper elements and connecting them to real society—not in the gimmicky action sequences and superficial jokes found in American blockbusters.

What exactly is fast-food culture? It’s presenting everything neatly stacked like a hamburger—no subtlety, no nuance, just straightforward simplicity. Admittedly, such simplicity facilitates international appeal. Yet as we grow increasingly familiar with—and immersed in—the fast-food culture of American animation, we must revisit The Monkey King. Here we encounter Chinese wisdom and culture, an understated and profound beauty, and the allure of language that speaks volumes beyond its surface. It transcends mere flashy display.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Monkey King 2012 Animation Film Review: A Culture of Subtext