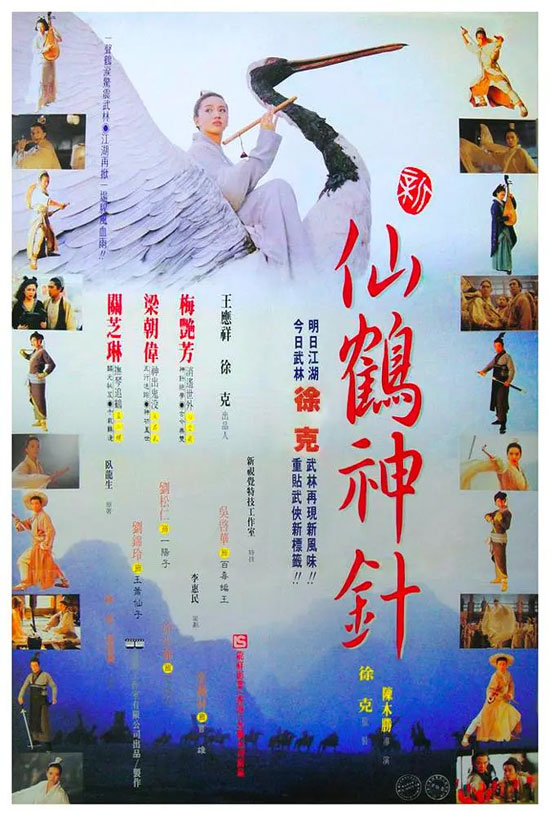

Film Name: 新仙鹤神针 / The Magic Crane / 新仙鶴神針

Among the many Hong Kong martial arts films, “The Magic Crane,” directed by Rene Chen, stands out as uniquely ethereal and mystical. Many fans hold a special place in their hearts for this film precisely because of Anita Mui’s unforgettable appearance—clad in white, playing a bamboo flute, soaring aloft on a crane. Indeed, when it comes to character design and cinematography, “The Magic Crane” stands as a rare cinematic masterpiece. Even more valuable is the profound reflection and playful exploration of the martial arts world embedded within the film by its creators.

Speaking of wuxia films, unforgettable, breathtaking scenes often flash to mind first. Take the ethereal sword-flying sequences in “A Chinese Ghost Story II” , the ethereal flight of swordsmen in “A Chinese Ghost Story II,” the resolute sword-slicing through water by Murong Yan in “Ashes of Time,” the agile sword-control by Linghu Chong in “Swordsman 2,” and the frenzied destruction of cannons by Dongfang Bubai in “Swordsman 3.” Yet The Magic Crane remains an indispensable masterpiece. Two peerless women harness the power of sound waves through their pipa and xiao flute, unleashing thunderous divine might that stirs the soul. The scene where the eccentric hero Bai Yunfei soars through the skies atop a crane, flute in hand, radiates an otherworldly, ethereal beauty.

Though Hong Kong may not rival Hollywood’s advanced special effects, the uniquely Eastern aesthetic captured in these homegrown cinematic masterpieces transcends what Western visual effects technology can easily replicate. Only creators with a profound understanding of traditional Chinese culture and aesthetics can grasp this ethereal beauty—something that can be felt but not fully expressed in words. It’s akin to foreigners watching the chase scene between Li Mubai and Yu Jiaolong in “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” and exclaiming, “Chinese people can fly!” without grasping the transcendent wisdom of unity with nature and self-forgetfulness embodied in that soaring flight.

The art and costume design in the film “The Magic Crane” are breathtakingly beautiful, yet the story is the exact opposite. Instead of the tranquil serenity of a utopian paradise, it is filled with scheming conflicts and grudges. This martial arts world mirrors the mundane realm of “falsehood, ugliness, and evil” that Fahai saw in “Green Snake.” Despite its heavy worldly atmosphere, the film offers moments both laughable and thought-provoking. In this somewhat apocalyptic martial arts world, practitioners without flags face discrimination from fellow martial artists, weaker sects are relegated to sleeping in wood sheds, and smiles often conceal hidden daggers. Throughout, the creators’ subtle satire and mockery of reality are evident.

Although Tsui Hark is credited only as an executive producer in this film, fans familiar with Hong Kong cinema know that this style of humorously critiquing reality—especially satirizing internal strife and the decline of moral values—is precisely the masterful specialty of the eccentric director. This visionary director consistently maintains a coldly observant stance toward reality, embodying the air of one who has seen it all. Yet, unlike Linghu Chong, Tsui Hark cannot transcend the mundane world despite his worldly insight—for he possesses an artist’s self-awareness and emotional depth. Thus, through characters like Wong Fei-hung, Linghu Chong, The Invincible East, Ning Caichen, Fang Hongye, Ding Yin, and others to express his own confusion, contemplation, and even painful bewilderment. This film, The Magic Crane, is no exception.

When the peerless hero Bai Yunfei first appears in this film, clad in white robes and accompanied by a white crane, the fresh flute music evokes an otherworldly, ethereal aura beyond words. Moreover, the plot design positions this character as newly entering the martial arts world. Contrasted with Tony Leung’s sly, worldly-wise portrayal, she seems like a celestial maiden untouched by earthly concerns. Calling her “unblemished by the world” at this point is no exaggeration. Yet, as the film itself states, the martial world is a vast dye vat—a place where human hearts are treacherous and right and wrong blur. Significantly, scenes set in dye shops appear repeatedly throughout the movie. After her master’s death, Bai Yunfei’s attire shifts to dark colors, while Lan Xiaodie, who previously wore dark clothing, now dons white. The stark contrast in colors and their differing postures reveal how profoundly the martial world has altered them.

In truth, the term “jianghu” here carries a different meaning than its conventional usage in martial arts fiction. The true Jianghu stands in opposition to the imperial court, much like Fan Zhongyan’s verse: “When seated in the lofty halls of government, one worries for the people; when dwelling in the distant Jianghu, one worries for the ruler.” The Jianghu is a realm of carefree wanderers, a place of unbound freedom. The phrase “Let us join hands and lose ourselves in the Jianghu” further cloaks this idealistic realm in a veil of romantic beauty. The “jianghu” depicted in martial arts films is better termed the ‘wulin’ (martial world), as it diverges significantly from the authentic essence of the Jianghu. “The Magic Crane” explores both these distinct interpretations of the Jianghu. Bai Yunfei, upon first entering the Jianghu, witnesses the shameless faces of its inhabitants, becomes entangled in complex vendettas and injustices, and ultimately sinks into the quagmire of hatred. In Swordsman 2, Ren Woxing declares, “Where there are people, there are grudges; where there are grudges, there is the Jianghu. People are the Jianghu.” This reveals that in most eyes, the Jianghu was never a tranquil realm—this idealized pastoral was no different from the mundane world. In fact, the Jianghu depicted in The Magic Crane was even constrained by official authority. In contrast, the mountain wilderness where Bai Yunfei once lived represents the true martial world—a place untouched by grudges or passions, where even imperial robes and crowns fade away with the wind, leaving only a pure heart.

When asked what defines a true hero, Tsui Hark replied, “One who can let go of worldly values.” This embodies a kind of magnanimity—a transcendent and expansive spirit. The martial world in “The Magic Crane” is mundane because its inhabitants are ordinary people, not heroes. Consequently, its protagonists are not free-spirited recluses but rather those entangled in grudges and enmity. I’ve long pondered why the film is titled “The Magic Crane and the Divine Needle.” The crane makes sense, but what of the divine needle? Upon rewatching, I realized the divine needle represents grudges. Lan Haiping used an intangible divine needle to heal his daughter’s wounds, yet wielded a tangible one against Cao Xiong. One thought of compassion led him to sacrifice himself for his daughter—a bond of kindness. Another thought of vengeance drove him to pierce his enemy’s body—a bond of hatred. These entanglements of affection and resentment are both the essence of emotion and the root of the martial world’s endless strife.

Whether Lan Haiping or Bai Yunfei, no matter how supreme their martial arts, they cannot escape the martial world. The day Bai Yunfei stepped into this world sealed her fate—she could never return to her former innocence. For they possess emotions, and thus find themselves burdened by debts of gratitude and enmity. Even if these roles subtly shift, they cannot be cast off. “The immortal crane has vanished with the clouds, yet the divine needle still bears the moon’s chill”—these lines capture it perfectly. Even when one retires on a crane, the divine needle retains its moonlit coldness. Its brilliance fades not with distance from the martial world, for where there are people, there are debts and grudges; where there are debts and grudges, there is the martial world. Does the true “martial world” truly exist? If so, why must Bai Yunfei confront the debts and grudges he carries? Perhaps that world is merely a fragile, mirage-like spiritual refuge. Or perhaps it represents a transcendent mindset—keeping the martial world in one’s heart while dwelling in the mundane world might allow for a lighter existence. Take Ma Junwu from the movie—utterly devoid of ambition for fame or fortune. In the end, he and his master carried the banner of “Martial Alliance Leader” out of the martial world, returning home to run a business. His life was simple, authentic, and deeply satisfying.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Magic Crane 1993 Film Review: The Jianghu is a kind of magnanimity.