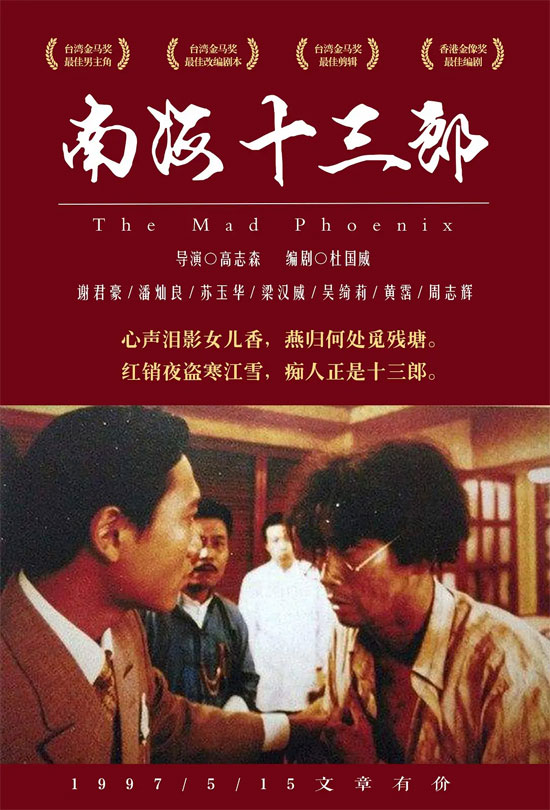

Film Name: 南海十三郎 / The Mad Phoenix

I have a cousin who is exceptionally bright, possessing a photographic memory. Her IQ test results upon entering school were exceptionally high, prompting the school to advise her parents to send her to a specialized institution. The elders in our family were immensely proud, but I alone opposed the idea.

“Never presume yourself a genius, for true geniuses face only two fates: either they go mad early like Nan Hai Shisan Lang, or they die young like Tang Disheng.”

These words came from a down-and-out screenwriter, tinged with a quiet resentment—resentment toward a world that seemed heartless, even driving a generation’s prodigy to despair. Was he lamenting genius, or using genius to voice his own frustrations? We cannot say. All we know is that both Shisanlang and Tang Disheng had such brilliant moments that their long lives seemed especially futile and jarring in the shadow of that starlight.

In 1984, Nanhai Shisanlang—Jiang Yulong—passed away at seventy-four. He lay barefoot on a winter night in Hong Kong, as we are born barefoot. A kind-hearted policeman quietly slipped shoes onto his feet. His long journey through life had been arduous enough; may his path to the afterlife be peaceful.

From childhood, he lived in luxury and was gifted with exceptional intelligence. After studying in Hong Kong as an adult, he fell deeply in love, dropped out of medical school, and followed his lover to Shanghai. When the romance ended, he returned to Hong Kong. Obsessed with opera since childhood, at twenty he wrote the play “Han Jiang Diao Xue” for renowned Cantonese opera star Xue Juexian. Overnight, his name spread far and wide. Every Cantonese opera he penned sold out, touring Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau. Young and famous, he brimmed with ambition and pride—ordinary folk scarcely registered in his eyes. His ideas flowed like a spring, enabling him to draft multiple scripts simultaneously. He would act out the singing, reciting, and fighting scenes himself, fan in hand, swaying his head rhythmically as he composed. How many true connoisseurs existed in his time? His sheer speed of thought and speech alone were beyond the reach of ordinary mortals. He felt stifled, irritated, and profoundly lonely. and being naturally innocent and straightforward, he couldn’t hide his feelings. He dismissed all his stenographers, only to have a young man arrive seeking to be his disciple. This youth wore simple clothes and had a gentle temperament, yet possessed an unyielding spirit. That was Tang Disheng—his dear friend, his apprentice, his younger brother, his Zhiqi. Two lonely geniuses clicked instantly, harmonizing and sparring in perfect rhythm—truly a magnificent spectacle! Those were indeed golden days, the most dazzling and vibrant moments in the entire film, making the tumultuous fortunes of their later years all the more poignant.

Throughout his life, he witnessed the joys and sorrows of reunion and separation, the shifting tides of time, ruins and skyscrapers. By thirty-four, he had already lost his mind, yet somehow stumbled on for another forty years! What strength it must take to cling to memories so relentlessly. Why didn’t he choose death? Did he even scorn death itself? The right to end one’s life is humanity’s final, sole privilege. Yet this brilliant, mad genius lived a full seventy-four years. Where did he find the courage?

Where did he find the courage…

Only that painting holds the answer. Yes, “Snow Mountain White Phoenix”—a blank sheet of paper. What do you see? A child sees snow-capped mountains, a phoenix pure as snow. What do you see? I see only utter absurdity. I see the phoenix arrive, I see it fly away. I see his fleeting worldly glamour, I see his monastic tranquility, I see fame and fortune vanish in an instant, I see wealth and glory prove but a play.

In the end, it’s all emptiness. Birth and death—what is there to cling to?

Perhaps Heaven took pity on his half-life of wandering, pity on his life of hardship and displacement, and finally allowed master and disciple to meet again. After years of madness and begging, in this mundane world, his sole solace, his one soulmate—he finally encountered Tang Disheng again. That Tang Disheng, the very Tang Disheng who declared, “I will prove that literature has value!”

“Our reunion feels like a dream. Since our hasty parting, Now we meet again, yet a thousand miles apart. Seeing my master once more, my heart aches deeply, Like a sword half-buried in mud and dust. My former ambitions and talents lie shattered. Snow on the river, tears blurring my vision— I’ve betrayed the Bo Ya’s zither. (You needn’t struggle to control yourself.) To seek a kindred spirit once more, (Worldly affairs have yet to subside).”

He was waking, finally waking. Tang Disheng told him, “Friend, let us seek those good old days once more! Let us start anew!” Recalling those rugged years, his dim eyes flashed with a long-lost brilliance. At this point, I could bear to look no further—endless sorrow engulfed me. I knew how joyful reunion could be, and how cruel what followed would be. Just as he rallied his spirit, ready to return to the world, invited by Tang Disheng into the theater, he witnessed Tang Disheng’s sudden death from a heart attack. He finally collapsed completely, his mind gone.

Yet he still did not die. Five years later, he emerged from the psychiatric hospital. His niece had converted to Christianity and earnestly urged him to join her faith. He smiled. “I have faith,” he said, “only this faith too is empty.” He ultimately entered the Buddhist order. I secretly rejoiced—let him spend his remaining days in the temple. Let it end… Unexpectedly, a blind man who came to pay respects at the memorial altar brought news of his father’s death. This was his last earthly attachment. From then on, he truly had nothing left. “Where are you going, Shisanlang? Does the abbot know you’re leaving?” “Going up the mountain is easy; what’s so hard about coming down?” He smiled softly.

Years later, people recounted his story on bustling city streets. Decades more on, others watched his tale unfold on television screens. It was the most magnificent voice from a grand era—a world vast enough to hold a genius, yet too narrow for him to thrive. And here we remain, mired in petty struggles, caught in the cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death. In that moment, I wept uncontrollably.

He was a man both vulgar and detached, possessing childlike innocence, He loved and pitied all beings, passionate and true. His vulgarity lay in his yearning to one day fulfill his ambitions, to achieve greatness. His detachment stemmed from his seemingly mad yet profoundly lucid final four decades, when he finally understood: before fate’s emptiness, all our struggles are so insignificant, so pitifully small.

“I am a man of the South Sea, the thirteenth son in my family. Henceforth, I shall be known as Nan Hai Shi San Lang!”

The closing theme of the TV drama “The Mad Phoenix” features a beautiful melody with lyrics that go like this:

You need not ask my name. Look upon the endless night stars—

They still illuminate this fleeting moment of your heart.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Mad Phoenix 1997 Film Review: A page filled with absurd words, a handful of bitter tears.