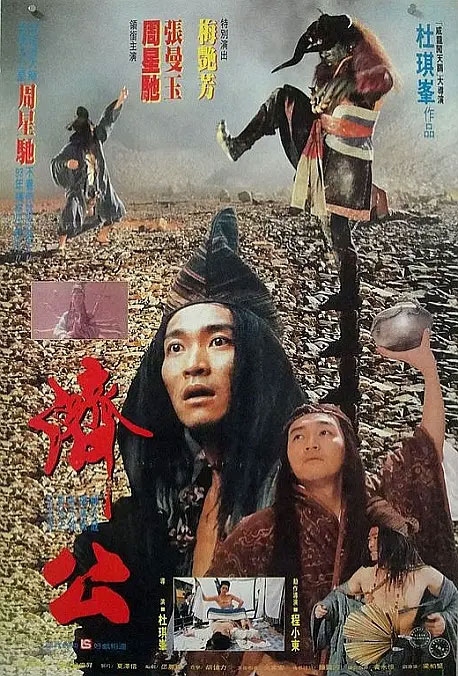

Film Name: 济公 / The Mad Monk / 濟公

This is one of the few Stephen Chow films where he doesn’t engage in a romantic storyline with a “Star Girl.” The Mad Monk’s greatest strength lies in its grand scale.

Perhaps due to the addition of the ultimate showdown with the boss, King Yama, featuring fight scenes that seemed truly “heart-pounding” for that era, the film breaks free from the “small-scale” feel of previous Stephen Chow productions.

Initially, I wondered why CGI wasn’t used for the final battle. After all, the opening scene featuring Guanyin’s arrival (the lotus blossoming sequence) employed digital effects. But then I realized that with the limited special effects technology available at the time, creating such a large-scale CGI scene might not have achieved the desired perfection. Moreover, filming on location allowed for a more authentic, “heart-pounding” texture.

While there is absurd humor in Ji Gong Li, it serves only as a supporting element. It’s like a dish where the absurdity acts as a garnish, while the main course remains the excellent storytelling and scene direction.

The film’s narrative is truly its most compelling aspect. Ji Gong initially descended to the mortal realm to save humanity, driven by a desire to prove “he could help people reform” and demonstrate “compassion exists in the world.” Yet subsequent events reveal: Ji Gong could never accomplish this mission through his own strength alone.

The Nine Lifetimes of the Wicked Man, the Nine Lifetimes of the Prostitute, and the Nine Lifetimes of the Beggar seem to embody the Buddhist concepts of anger, greed, delusion. From Ji Gong’s perspective, he exhausted every possible method to save these three souls—yet neither his magical feats nor his sermons could restore the beggar’s dignity. Neither his self-sacrificing rescue nor his dream-based teachings could awaken the courtesan. And even a brutal beating failed to reform the villain. The transformation of these three individuals stemmed from self-awakening. The beggar awakened to protect the woman he loved, the prostitute because she could not attain the love she desired, and the villain upon realizing he had been exploited. Their awakenings arose from their own experiences, not from heeding Ji Gong’s teachings—or perhaps Ji Gong was merely a guide, not a shaper.

Ji Gong’s conduct in the celestial court portrays him more as a “rebel” and “challenger.” He rejects the celestial hierarchy’s dogma, believing instead in “human compassion” and his own power to reform mortals. One scene depicts the power struggles within the celestial bureaucracy—was this perhaps a deliberate satire by Johnnie To and Shao Li-ching on the systems of TVB and Shaw Brothers Studios?

A uniquely striking moment is Maggie Cheung’s awakening scene where she slashes her face—a visually stunning sequence. The shot of blood dripping down her cheek creates an uncanny echo of “Green Snake.”

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Mad Monk 1993 Film Review: An Atypical Stephen Chow Comedy