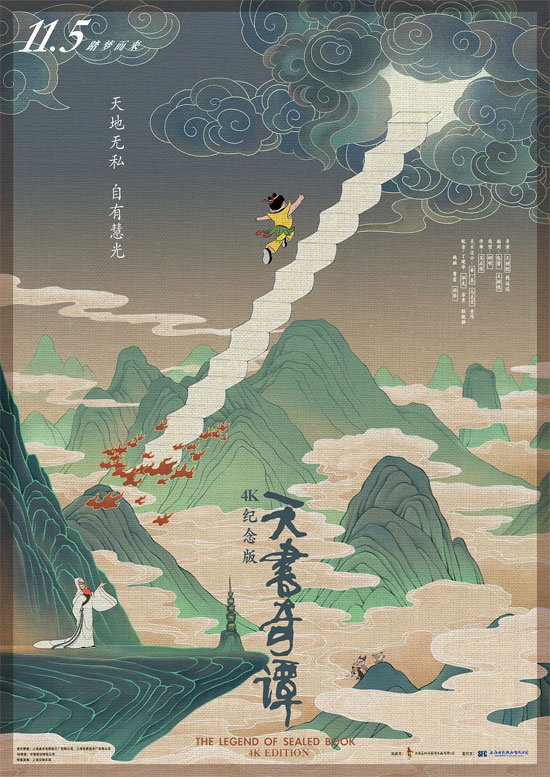

Film Name: 天书奇谭 / The Legend of Sealed Book / Secrets of the Heavenly Book

What defines a classic? It is a work that retains its powerful vitality even after enduring the test of time. “The Legend of Sealed Book” is undoubtedly a classic that has earned its place in the annals of Chinese animation history.

Produced by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio in 1983, “The Legend of Sealed Book” stands as the third animated feature film created after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It bears the distinct imprint of its era. On one hand, the ideological liberation brought by reform and opening-up loosened the constraints on the film’s expressive power. While upholding its people-centered nature, the film incorporated numerous humorous elements—a stark departure from the “serious dramas” of animations like “The Monkey King” and “Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King.” Initially conceived as a co-production with the BBC, it further aligned with the era’s theme of “openness.” Yuan Gong’s theft of the Heavenly Book mirrors Prometheus’s theft of fire, opening a new window for humanity to understand the world and granting ordinary people a key to reshape it—a metaphor for the dawn of ideological liberation.

Conversely, the film retains inherent patterns of socialist artistic creation from its era, such as emphasizing social utility and crafting archetypal characters. The film’s core theme of “punishing evil and promoting virtue” represents its greatest social utility. In the terminology of the time, this was the work’s educational significance; today, it would be described as the “positive energy” viewers are meant to gain after watching.

The character “Dànshēng” embodies the archetype of a young hero—moral, skilled, and using his abilities to aid the common people. However, he lacks a distinctly individualized personality. He can be seen as a slightly more lively and mischievous version of “Ma Liang.” This stands in stark contrast to many adolescent heroes in contemporary animation, who possess strong personalities and formidable skills but often lack admirable moral qualities.

The 1980s marked the second peak in the history of Chinese animation. Overall, this period saw a further strengthening of national expression in artistic terms and the formation of a methodological approach centered on “overall conceptualization” in creative work. These characteristics are both evident in The Legend of the Sealed Book.

The film carries a richly Chinese flavor. From its adaptation of the Ming Dynasty supernatural novel “Ping Yao Chuan” to its character designs blending the charm of traditional art forms like opera and New Year paintings, and even extending to its ethnic music and the intonation of the voice acting, all elements deliver a powerful sense of Chinese identity to the audience.

The “overarching concept” approach involves establishing a core theme first, then weaving the plot, characters, art direction, sound design, and other elements around this theme to create a cohesive, soulful whole. For instance, if the theme is “punishing evil and promoting good,” the depiction of evil must be utterly repulsive, while the punishment of evil must be deeply satisfying.

In the film, the county magistrate’s henchmen plunder citizens’ possessions at will, the prefect brazenly forces young women into marriage, and the emperor takes pleasure in watching tigers devour commoners—all vividly embodying “evil.” Conversely, the father who conjures eight county magistrates, uses the treasure basin to reclaim stolen goods, tramples the fox spirit disguised as the prefect, and causes the beam collapse that brings tears to the cynical emperor—these are pivotal moments illustrating “punishing evil.” The film lavishes detail on these scenes, leaving a lasting impression on audiences. This contrasts sharply with contemporary animation, which often prioritizes fantastical landscapes and grand battle sequences without justifying why such spectacles exist or why the fights occur—a fundamental difference in creative methodology.

Today, “The Legend of Sealed Book” has been remastered in 4K HD and re-released, still drawing large audiences. Beyond nostalgia, three timeless strengths make it unmissable.

First is the character design. Every figure in the film—from their appearance and artistic elements to their movements, voices, and personalities—has been meticulously crafted. This holistic approach to creating believable characters through multifaceted design offers valuable lessons for contemporary animators.

Second is the texture of hand-drawn animation. In today’s era dominated by 3D animation, works like The Legend of Sealed Book, which possess the artistic charm of 2D hand-drawn animation, are increasingly rare. This charm lies in the imagination of shape transformation and the mastery of rhythm. For instance, in the scene where the tiger and dragon battle, objects on screen deform at an astonishing speed, creating a feast for the imagination. Simultaneously, the distinct walking rhythms of different characters accompanied by different music are another major feature of the film. The county magistrate’s palanquin bearers have their distinct gait; the legless emperor walks in his own unique way; even the two shopkeepers carrying their poles exhibit two different rhythms—one lively and cheerful, the other melancholy and subdued. These simple walking animations perfectly showcase the charm of 2D hand-drawn animation.

Third is the subtle, satirical metaphor. Monks are meant to renounce worldly desires, yet in the film, they fight over possessions and succumb to the allure of a fox spirit. Officials are supposed to serve the people, yet every bureaucrat in the film finds new ways to oppress the common folk, revealing the inherent flaws of feudal society. In truth, these oppressive officials possess far more “demonic nature” than the fox spirit—they are demons in human form. The film portrays societal realities through exaggerated animation, using a child’s perspective to reveal the absurdity of the adult world.

Several neutral expressions in the film also merit attention. For instance, the two monks are initially satirical figures, yet after enduring separation and reunion through life-and-death trials, master and disciple ultimately reconcile. This avoids the formulaic portrayal where negative characters inevitably meet grim fates.

Similarly, even the three fox spirits—the primary antagonists—are not entirely irredeemable villains. After stealing three elixirs, the mother fox does not hoard them but shares them with her companions. Faced with the crippled Ah Gua, who has lost a leg and seems useless, she refuses to abandon him. She insists he join their journey to see the emperor, even risking exposure for deceiving the sovereign. This reveals a sense of solidarity and camaraderie within the fox community. Their survival-driven actions—seeking opportunities in caves or secretly studying celestial texts—are not inherently wrong. The true fault lies with the societal environment that makes survival impossible for foxes, and with the corrupt officials at every level who constantly tempt fox spirits into using their powers for evil. In fact, neither the film nor the original “Ping Yao Chuan” deliberately pushes demons into the depths of evil. Instead, they explore the theme that some humans are worse than demons, and that a corrupt society is the true breeding ground for monsters.

Of course, the film has its limitations. For instance, the narrative unfolds too straightforwardly, lacking dramatic peaks. Particularly due to the characters’ stereotypical traits, the emotional impact of the pivotal scene where Master and Disciple part ways feels underwhelming. Cinematography is somewhat flat, with almost no close-ups or special effects shots. Characters predominantly move side-to-side within the frame, lacking the three-dimensional depth of vertical movement.

It must be said that remastering classic films is a vital strategy for brand revitalization. Shanghai Animation Film Studio has reintroduced numerous classics like The Monkey King, The Gourd Brother, Inspector Black, and Dirty King Adventure through 3D conversion and high-definition remastering, sustaining the vitality of these animation franchises.

However, we must also recognize that re-release alone is insufficient for sustaining a brand’s vitality. Both the market and audiences anticipate new stories based on these classic works and iconic characters. I have consistently advocated transforming the tale of Dànshēng battling the three fox spirits from The Legend of Sealed Book into an animated series with an expandable storyline. This approach aims to extend the lifecycle of classic works more effectively through innovative storytelling.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Legend of Sealed Book 1983 Animation Film Review: Seeing the absurdity of the adult world through a child’s eyes