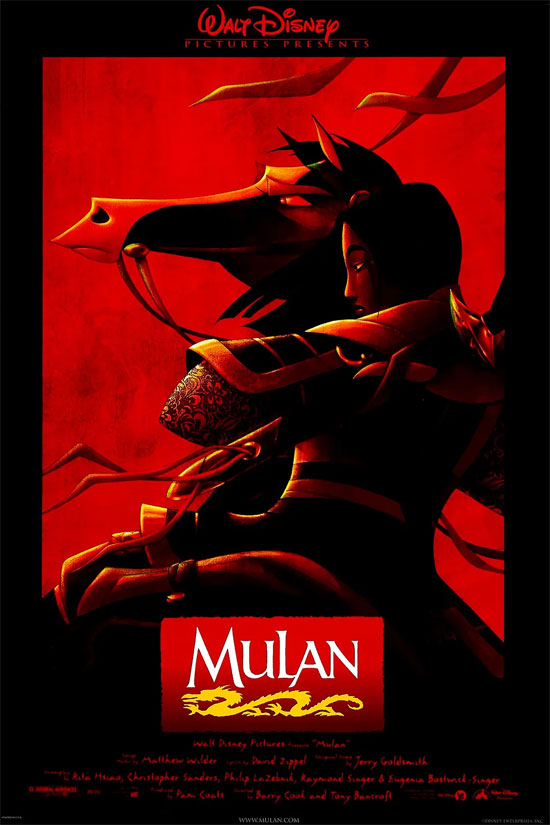

Film Name: 花木兰 / China Doll / The Legend of Mulan

Saying I’ve watched this animated film 100 times would be an exaggeration, but 50 times? That’s no stretch. Not for any other reason—purely because I love it.

Though it borrows from an ancient Chinese tale, it’s unmistakably American in spirit: creative, dedicated, and made with genuine care for children—yet captivating audiences of all ages. That, I believe, is the true essence of animation. Above all, its dedication is most admirable; only through such earnestness can a classic be born.

You can tell if a film is meticulously crafted after just one viewing, but to grasp its true refinement, you need a magnifying glass to dissect every detail. Having watched it fifty times and still finding joy in it, I can confidently declare Disney’s “The Legend of Mulan” an exquisitely crafted masterpiece—a classic among classics, nothing short of perfection.

Now, witness the Americans’ dedication.

1. Humanity—Interpreting Death Through Beauty:

Animated films are inherently for children—you may disagree, but you must acknowledge this film is aimed at young audiences. Thus, despite depicting war and slaughter, no bloodshed is visible beyond the faint trace of blood from Mulan’s wound.

In that breathtaking snowy mountain battle, the Hun army’s losses were reduced to mere stragglers—not by swords, spears, or clubs, but by an avalanche. What a thoughtful concept! All the cruelty is veiled in poetic whiteness.

The Khan’s demise is rendered even more beautifully: he transforms into fireworks, scattering vibrant colors across the palace sky at midnight. What a whimsical touch—the beastly Xiongnu achieve their final romance through death.

The annihilation of Li Xiang’s father’s entire army is conveyed through the charred ruins of battle. A single helmet, a rag doll—these suffice to convey death’s message. Without confronting bloody reality, they still evoke profound sorrow. This art of implication is a true legacy of Chinese culture.

Such examples abound. Only those who wholeheartedly consider children would exert such effort.

2. Shadows—Vividness in Perfect Measure

The presence and quantity of shadows in a scene serve as my personal benchmark for judging the quality of an animated blockbuster (excluding alternative styles like ink-wash animation). We all know oil paintings demand strict adherence to light and shadow for realism and depth. While animation doesn’t pursue hyper-realism and often omits shadows, the true perfectionists don’t just avoid them—they strive for the best possible execution.

The artists behind “The Legend of Mulan” demonstrated what dedication means—where there is light, there must be shadow. Their most impressive work is on the snowy mountains, where the Hunnic army surges densely across the horizon, charging like a tidal wave. Using an aerial shot, they rendered shadows for every horseman, until suddenly an eagle’s shadow streaks across the sky. Amidst the tumult of thousands of horses and soldiers, the eagle remains utterly unobscured. Swift as lightning, yet perfectly visible—a stroke of genius, utterly vivid.

3. Expressions—Meticulous Depiction Without Compromise

The characters’ expressions are richly varied and exquisitely detailed. Many scenes last only seconds, yet countless frames were meticulously drawn. Take Mulan’s makeup session before her arranged meeting. As she crosses a street, two old men—one plump, one thin—play chess. One has the other in check. Mulan moves a piece, turning the tide. The expressions are exquisitely nuanced: the plump man shifts from a frown to shock, then wild joy, even schadenfreude. The thin man’s gaze undergoes a kaleidoscope of changes: first deep contemplation, then a smug, confident challenge, followed by the resolute certainty of a decisive move. Next comes arrogant arrogance, arms crossed and eyes closed, waiting to see how you’ll lose. Suddenly interrupted by a sound, his eyes widen in disbelief, followed by utter bewilderment, and finally, bitter resentment. All of this unfolds in just ten seconds. (Quick note: The skinny guy’s “general” piece moved diagonally.)

Ever notice the background actors—those extras behind the main characters? In most Japanese anime, whether TV series or even movies like Detective Conan: One-Eyed Flashback, non-speaking characters just freeze like statues. The one talking only moves their mouth, looking super stiff. In contrast, even the blurred background figures in “The Legend of Mulan”—those standing far off with no lines—show expressions. Take the scene where the name “flower vase” is coined: a group of bruised soldiers stand behind the three protagonists, listening to their comedic exchange alongside the audience. Most viewers wouldn’t notice them even after ten viewings, yet their figures aren’t static. One might tilt their head, another turn theirs—someone is always in motion. This visual alone commands our profound respect.

4. Prop Design—Subtle Clues Without Waste

I’ve always believed that fewer props are better in plays, and that each prop should serve multiple purposes. “The Legend of Mulan” embodies this principle. Take the cloth draped over Mulan’s steed: it serves as both a majestic adornment for the horse and a symbol of its tender heart. When Mulan hastily emerges from her bath, the horse uses it to shield her retreat. When Mulan is banished into the biting wind, the horse wraps it around her as a protective cloak. What a gentlemanly mount! Then there’s the paper fan. Initially used as a cheating tool during matchmaking, it becomes a life-saving weapon in the final hour, ultimately disarming the Khan. There are also elements that echo throughout the story, like the puppy and the hen. While these aren’t particularly ingenious ideas, the fact that the same object appears more than twice shows that the designers put thought into it. This is far more responsible than those directors who treat even their characters as disposable, summoned and dismissed at will.

5. Chinese Dubbing—Equally Outstanding

The Chinese translation and dubbing are equally outstanding, with virtually no loss of impact. Two details bear witness: When Yao snaps at Mulan, he says, “It’ll make your ancestors dizzy.” The pronunciation of “ancestors” requires a wide mouth opening, making a literal translation like “祖宗” impossible to match the lip movements. The Chinese adaptation cleverly uses “包你老祖宗两眼冒金星” (guaranteed to make your ancestors see stars), where ‘two’ (两) mirrors the original “two” (两) in the English phrase, effortlessly resolving the issue.

Another example is when the Prime Minister orders the troops: “Order, people order!” The original intent was likely to stand at attention for roll call, but the soldiers instead start ordering food. “I’d like a pan-fried noodle…” A literal translation would have ruined the humor. The Chinese version cleverly adapted it: “Still arguing? What’s the fuss about?” “I’ll have a scrambled egg with scallions.” Achieving the same effect—truly a testament to the effort put in.

Was this thanks to local stars like Jackie Chan, Chen Peisi, and Coco Lee, or the team hired at great expense by the Americans?

Back when news broke that Americans planned to film “The Legend of Mulan,” Chinese people erupted in fury—much like the outrage when Korea claimed the Dragon Boat Festival as their own cultural heritage. When the character designs for “The Legend of Mulan” surfaced, the anger intensified: How could they portray this heroic woman like this? The Americans didn’t even bother to respond, simply stating: “We researched the historical records; people looked like this back then.” The Chinese immediately fell silent, as no one had researched it and couldn’t refute them on the spot.

I haven’t researched it either, and I do think Mulan’s appearance doesn’t quite live up to the poetic imagery of “combing her cloud-like hair by the window, applying flower-shaped makeup before the mirror.” However, I believe the Americans did their homework thoroughly. The film is packed with Chinese elements: the Three Obediences and Four Virtues, ancestral worship, abacuses, chess, kites, paper fans, dumplings, lion dances, brushes, ink, paper, and inkstones, martial arts—everything imaginable except Peking Opera was included, deliberately crafted to highlight their charm. Chinese painting techniques were integrated into the artwork, and traditional instruments featured in the soundtrack. Reportedly, 600 animators worked on it for four years. Those two figures alone should make us shut up.

“To imbue the film with distinct Eastern charm, Disney dispatched a creative team to mainland China for field research. Their journey spanned cultural capitals like Beijing, Datong, Xi’an, Luoyang, and Dunhuang. They visited museums and art galleries across the country, even traveling to Jiayuguan Pass to witness the grandeur of the Great Wall firsthand, gathering extensive reference material. Moreover, hundreds of Disney animators devoted considerable time to mastering the refined, expressive artistic style and the philosophy of balance and harmony inherent in traditional Chinese art. They meticulously studied and emulated the techniques and aesthetics of Chinese ink painting.” What else can be said?

The only thing that infuriates me is that they borrowed Chinese stories, borrowed Chinese techniques, borrowed Chinese box office success, yet what they promoted was unmistakably American culture. And they weren’t wrong. I can’t even get angry about it—and that’s precisely what angers me the most.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Legend of Mulan 1998 Film Review: When Disney Meets Mulan