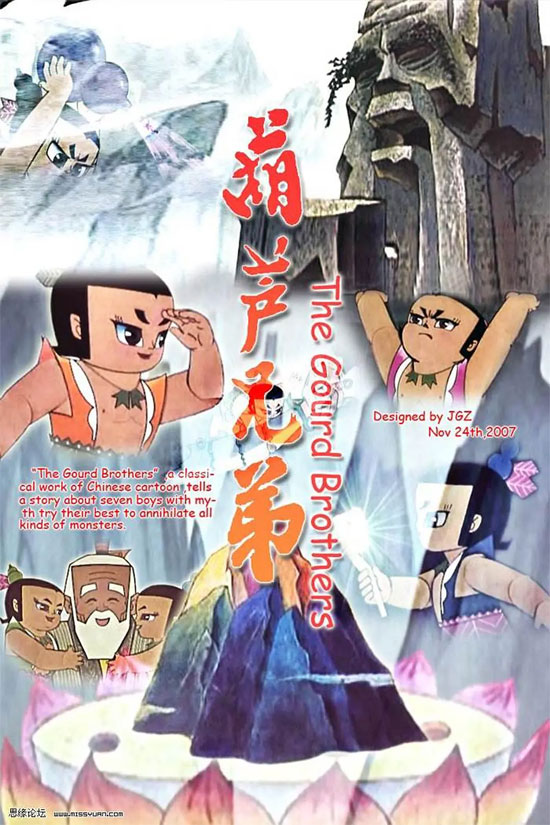

Film Name: 葫芦兄弟 / The Gourd Brother

Regarding China’s traditional animated films, there is actually much to explore in depth. For instance: Why does Nezha challenge four Dragon Kings in Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King, rather than just one? Why did the second part of “The Monkey King,” completed in 1964, only gain widespread circulation and popularity after the Cultural Revolution? As two of China’s most significant animated films, both “Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King” and “The Monkey King” feature the character ‘闹’ (nao, meaning “to cause trouble”) in their titles—is this mere coincidence?

In the widely acclaimed The Gourd Brother, there’s another peculiar setting: the snake spirit and scorpion spirit are actually married! Snakes are reptiles, and scorpions are arthropods—how could they possibly marry? Don’t underestimate this matter. Consider that Inspector Black Cat, roughly contemporary with The Gourd Brother, was a science-education hero film featuring factual knowledge like female praying mantises consuming males to nurture offspring. While one film diligently promoted science education, the other openly undermined it—how can this be explained?

In truth, once we recognize one fundamental truth, all these questions resolve themselves. That truth is the pervasive cultural ideology that shaped the themes of traditional Chinese animated films: class struggle. While not every animated film from that era centered on class struggle, at least eighty percent bore its distinct characteristics.

Earlier, in films like The Magical Pen, The Fisher Boy, and Ginseng Baby, class struggle was starkly portrayed as the conflict between the hardworking, kind-hearted peasant class and the ruthless, brutal landlord class. In these works, members of both classes appeared in their true forms. Later, our animated films adopted a metaphorical approach to depict the two opposing sides of class struggle. The term “stirring up trouble” originally referred to conflict, later extending to signify class struggle. In Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King, the protagonist battles four dragon kings—a symbolic representation of the overthrow of the Gang of Four, who were portrayed as class enemies. The Monkey King, depicting the theme of the underprivileged opposing the ruling class, was labeled reactionary and only regained normal distribution channels after the Cultural Revolution.

By the time “The Gourd Brother” was produced in the 1980s, China’s mainstream ideology had shifted from class struggle to reform and opening-up. Yet decades of ingrained thinking couldn’t vanish overnight. Works depicting the oppressed peasantry and exploitative landlords remained a significant theme in artistic creation. “The Gourd Brother” fundamentally depicts the struggle between peasants and landlords, though here the peasants are represented by an old man, while the landlord class is personified as snake and scorpion spirits. In truth, both the snake and scorpion serve only as symbolic representations—messengers of the landlords. Messengers of what? Messengers of the landlords’ most vile qualities. The female snake embodies cruelty, while the male scorpion represents violence. The union of the snake spirit and scorpion spirit symbolizes the fusion of these two worst traits found in landlords. As the saying goes, “a heart as venomous as a snake and scorpion,” “The Gourd Brother” cleverly borrows this ancient proverb. Through the union of snake and scorpion, it portrays the landlord class’s heart as venomous as a snake and scorpion.

Consider this: in “The Gourd Brother,” what represents the righteous side? The gourd. What is the gourd? A crop. If they don’t symbolize the peasant class, then who else could they represent?

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Gourd Brother 1986 Animation Film Review: Why can snake spirits and scorpion spirits get married?