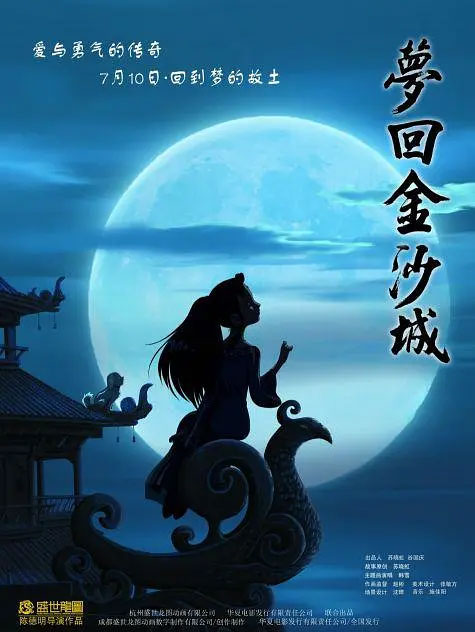

Film Name: 梦回金沙城 / The Dreams of Jinsha / Meng Hui Jin Sha Cheng

I can say with certainty that since “Lotus Lantern,” every domestic animated film I’ve seen, I’ve paid my own way to watch in theaters. They’re sandwiched between the annual influx of American animated blockbusters, so you can imagine the repeated heartbreak I’ve endured. Yet I persisted, time and again.

However, after watching “The Dreams of Jinsha,” the blow was simply too devastating.

I won’t dwell on the viewing conditions—American blockbusters always pack the house, while domestic animations draw only scattered viewers. This time, there were just three of us in the empty theater, including myself. The other two were a mother and her little boy, around five years old. The boy was quite mischievous, telling his mom, “If he weren’t here, it’d be so much better just the two of us!” A bead of sweat formed on my forehead. Still, the sparse crowd had its perks—I could easily observe the young viewer’s reactions.

But unexpectedly, this observation delivered another blow: I’d previously thought domestic animations catered to younger audiences, so it didn’t matter if young adults or adults found them lacking—they weren’t made for us anyway. As long as children enjoyed them, that was enough. Today, though, the first forty minutes had the little boy slumping in his seat, bored enough to nearly bang his head against the chair in front for entertainment. When the first interlude song started (just as the male and female leads were getting all lovey-dovey—visually pretty but plot-wise incredibly slow)—the boy yelled, “This is it. It was only after his mother reassured him there was more to come that he refocused slightly on the screen. He didn’t truly engage until the film’s antagonist—the forest’s dark force—finally appeared.

While one young viewer’s reaction reflects just a single case, it clearly shows that most of the film failed to captivate him—let alone me. This is the film’s greatest and most fatal flaw—the plot is simply too weak. As a movie where you can predict the ending from the opening, it lacks any tension in the middle. The first half of the film has almost no conflict whatsoever, with only a 10-minute climax at the end. This is truly amateurish and unacceptable.

Regular readers of my reviews know I rarely use the phrase “utterly terrible” to describe a film. After all, every movie is the sweat and toil of directors and screenwriters—if not for their achievements, then at least for their hard work. As a critic, I have little right to speak ill of others, and out of respect for their labor, I should hold my tongue. But after watching this film, the only title that popped into my head was: Ten Thousand Whys. Nearly every minute of this story presents a plot point I simply cannot comprehend. Below are a few examples—perhaps I missed something, so I’d appreciate your insights.

1. As I understand it, the jade pendant Xiao Long carries allows him to return from Sand City to reality and grants him the power to fight evil forces, but only one of these abilities can be active at a time. Otherwise, if Xiaolong stays to fight evil without sacrificing his chance to return to reality (though he eventually finds another way back), what depth would the story have? If he could have both, would his brave leap against evil still be called “sacrificing” himself for the greater good? Especially since the story seems to have dialogue hinting at this.

2. Why did Xiaolong possess this spirit jade? What connection did his family have to the ancient Jinsha Kingdom? True, his father was an archaeologist, but archaeologists are common—why did his family specifically hold this jade?

3. Why did the jade speak in the end? Initially, it only glowed at critical moments, signifying its power activation, but the film never revealed it could speak. Later, it actually tells Xiaolong what to do with it—was it possessed by some spirit? That feels illogical. Even the dog couldn’t speak, so why could the jade?

4. When Xiaolong was brought to the museum by the dog, the guards’ flashlights couldn’t detect him. Yet this invisible boy was picked up by electronic surveillance—doesn’t that seem odd?

5. At the beginning of the film, Xiaolong runs over someone’s oranges with his bicycle. While this clearly sets up the scene where he helps the old lady pick apples at the end—a callback meant to show how Xiaolong has become more considerate and compassionate after his adventures in Sand City—it still feels odd. The oddity lies in the fact that Xiaolong wasn’t an unkind child to begin with—he cherished his pets and respected his parents. Yet the plot abruptly has him run over someone’s oranges. Moreover, his adventures in Golden Sand City offer no clear indication of how they shaped his character or values. In other words, the justification for his transformation feels insufficient.

6. After unlocking the seal of the dark power, the Archer General was immediately consumed by it. Did he offer no resistance whatsoever until the very end? Were his former bravery, strength, and most crucially—his desire to protect Golden Sand—utterly devoured? It makes no sense. Moreover, after being consumed, why did he transform into that monstrous, unrecognizable form? How could anyone possibly identify him as the original Archer General from that appearance?

7. Where exactly does the evil force originate? What do ancient legends say about the arrival of this evil force and the foreign emissary? This fundamental worldview remains entirely unexplained.

8. Did the evil force cause a locust plague? Why specifically a locust plague? It had been dormant in a forest tree hollow before being sealed—what connection does it have to locusts? Moreover, the evil force possesses a signature attack that emits a certain ray capable of igniting fires. This ability is completely at odds with the locust plague concept.

9. Why can the princess’s mount run on water? Is it a divine beast?

10. Before its destruction, the evil force made a lunging motion toward Jinsha City. Why didn’t it simply obliterate the city with its ray? What was its true purpose?

11. Given the Evil Force’s height, the width of its palm, and the beam’s power, each attack should obliterate at least a 4-meter square area. Yet when it targeted the fallen princess and the dragon flew to rescue her, the beam only shifted the princess 2-3 meters sideways while precisely destroying an area the size of a wooden plank. This feels implausible.

12. The elephant’s status as a guardian deity starkly contrasts with its utter vulnerability. Moreover, what exactly is the elephant’s connection to Sand City? The film offers no explanation whatsoever.

13. When the locust swarm first prepares to attack Sand City and the soldiers brace for battle, the insects suddenly retreat. Why? Were they frightened, or did they receive a call? It’s utterly baffling.

14. Where exactly is Sand City? Its architecture resembles China, its wall paintings Egypt, its elephant worship India, and many stone statues evoke Easter Island. If it’s a fictional blend of cultures, what purpose does this hybrid serve beyond merely incorporating diverse elements?

15. When Xiaolong arrives at Sand City and is discovered by the princess and the archer, the princess wears a butterfly-shaped mask. Why does she wear this mask? Did she anticipate encountering strangers? She never uses this mask again afterward.

16. Does the character of the scholar-official serve no purpose beyond performing mystifying divinations and sacrificial rituals? Surely he could have achieved something before his death.

Finally, I must ask: What truly defines the personalities of the protagonists, the Dragon and the Princess? After 80 minutes of character development, they remain utterly flat to the audience—figures who could vanish without a trace into the vast sea of animated characters.

This animation boasts first-rate backgrounds, second-rate character designs, third-rate action sequences, and a plot that’s practically nonexistent. But to think that mere visual splendor alone can elevate a work to market-demanded standards is a grave mistake. Two cases warrant particular study: the theatrical versions of Pleasant Goat, which achieved box office success without such elaborate visuals; and the works of Hayao Miyazaki, whose unparalleled style nonetheless struggles at the American box office. Why is this? Furthermore, why have our cinemas in recent years exclusively imported American animated blockbusters, consistently achieving strong box office results? Connecting this trend to the two cases above—what does it reveal? I believe the answer is self-evident. If I may offer one suggestion: during the scriptwriting phase, please consult as many individuals knowledgeable about animation and screenwriting as possible. If nothing else, even showing me the draft would be an improvement over the current situation.

If there’s one small consolation after watching this film, it’s the sincerity evident in its world-building. For that sliver of comfort alone, I’ll keep returning to theaters to watch domestic animations time and again.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Dreams of Jinsha 2010 Animation Film Review: Dreamy domestic animation, please come back to reality.