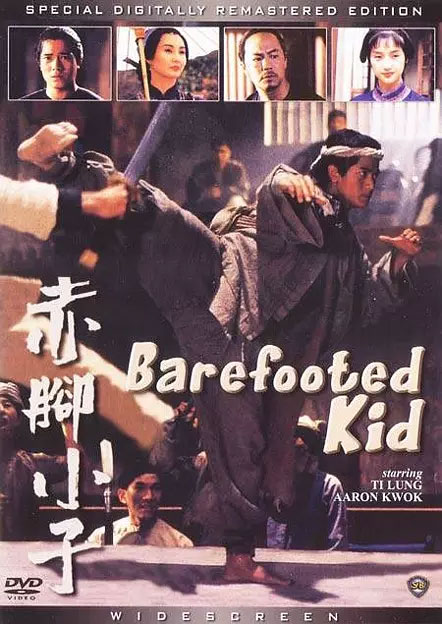

Film Name: 赤脚小子 / The Bare-Footed Kid

Johnnie To’s 1993 film. I’d seen bits and pieces on TV before, leaving some impressions. Watching it in full this time, I was moved by the emotions within. Not here to critique the film’s merits or flaws, just to share some memorable moments.

Barefoot and Shoes

The Barefoot Kid (played by Aaron Kwok), penniless and illiterate, arrives barefoot in the provincial capital seeking refuge with his father’s friend, Duan Qingyun. Duan Qingyun, now using the alias Duan Nan, has settled at the “Four Seasons Weaving Factory,” and the Barefoot Kid stays there too. He meets Xiaolian, a girl from a scholarly family. Despite a series of misunderstandings, their bond deepens over time, and Xiaolian even teaches him to write his own name. From Duan Qingyun, Barefoot Boy received his first pair of shoes. Though they were too big and ill-fitting, they filled him with excitement.

Though Four Seasons Weaving provided a decent shelter, the provincial capital was far from peaceful. The city teemed with fighters from all regions gathered for the tournament, vying for profit through brutal combat. The local criminal syndicate, Kahabu, wielded influence backed by central government connections, operating with impunity and arrogance. The newly appointed local official was determined to root out these criminal forces, though his actions seemed more aimed at establishing his own authority, with others merely pawns in his scheme.

When Barefoot Kid first arrived in the provincial capital, he was full of innocence, seeking only a job and an ordinary life. But the events he witnessed forced him to change. He immediately noticed the beauty and kindness of the shop owner, yet her Four Seasons Weaving faced relentless hostile takeover attempts. He stood up for the shop, only to offend Kahabu and be forced to leave. He fell in love with Xiaolian, yet her father disapproved, denying him a farewell before departure (their exchange was telling: “Who is he?” “He works at Four Seasons Weaving.” “What future is there in that?” “He studies diligently and wants to attend school here.” “Your senior apprentice toiled ten years for his achievements—think about it.” “He knows martial arts too.” ” A mere warrior? At best, he’ll end up risking his life for others. He’ll never amount to anything.”); Finally, when boarding the ship, he was kicked off because someone else offered more money. He had seen the coldness of the world and endured deceit and injustice. Without money or power, he was destined to be bullied. So he chose to stay, entered the tournament, and eventually became Kahabu’s subordinate. Under Kahabu, he earned the title of Chief Instructor and received a pair of fine new shoes.

The barefoot boy’s bare feet were clearly more than just a superficial touch of humor. As the saying goes, “The barefoot man fears no shoes,” yet this carries a sense of the underdog’s psychology, tinged with a hint of reluctance. Bare feet represent a primal state—unspoiled and immature. He would soon embark on his journey of growth, seeking his shoes. First, he received a pair of ordinary cloth shoes from Duan Qingyun. Though worn, they were sturdy enough for traversing mountains and rivers, allowing him to walk with solid footing. Unfortunately, he was still too naive and immature. Duan Qingyun’s shoes were too big for him. The hardships of life and the patience required to navigate the world were lessons he couldn’t grasp in a short time. Life’s injustices fueled his refusal to settle for mediocrity. He resolved to find new shoes for himself. At Kahabu’s place, he earned a pair of beautiful new shoes. In truth, he hadn’t aided the tiger—it was merely a transaction where each pursued their own ends. Yet this came at the cost of abandoning morality and justice. Putting on the shoes meant losing his former innocence, and what he gained might not hold the value he imagined.

Mirroring the theme of bare feet versus shoes is the Barefoot Boy learning to write his own name. This isn’t merely progress from illiteracy to literacy. If bare feet and shoes represent shifts in identity and the search for recognition, then learning to write his name signifies a form of self-affirmation and return to his roots. When he finally dons new clothes and shoes, able to walk tall among people, he instead faces Xiaolian’s contempt. Ultimately, he hands Xiaolian a neatly written note bearing his name, ending his self-imposed exile to confront and resolve the wrongs and losses stemming from his actions.

In the end, the Barefoot Boy perishes alongside the villain. As death approaches, he struggles to put on the shoe that lies nearby. This tragedy of the Barefoot Boy has its own causes, yet in a sense, it is also an inevitability born of the larger environment. While growing pains can lead one back onto the right path, when the allure of gain and the corresponding setbacks arrive too directly and brutally, confusion becomes inevitable. Amidst this disorientation, there is rashness and risk-taking, there is understanding, and there is cost. Though the saying goes, “The innocent will be cleared,” for the average person in the crowd, it’s hard to remain unaffected. Moreover, this is something even individuals like Duan Qingyun and Xiaolian cannot help or resolve.

Rouge

The film is rich in emotion. On one hand, though the main characters aren’t fully developed, their core personalities shine through. Their traits intertwine with their fates, creating a deeply tragic atmosphere. On the other hand, the abundant musical score enhances the mood, particularly when portraying the romance between Duan Qingyun (Ti Lung) and the proprietress (Maggie Cheung).

The proprietress of Four Seasons Weaving, known as the Widow, was actually betrothed since childhood. Before they ever met, her fiancé died, becoming her late husband. She single-handedly supported the weaving shop, living a lonely and pitiable existence. Meeting a man like Duan Qingyun—loyal, honorable, and deeply masculine—it was inevitable that their feelings would grow over time. The landlady did not dwell on Duan Qingyun’s past and even shared her dyeing secrets with him, showing profound trust. Yet, due to their differing statuses, their relationship remained perpetually elusive.

One rainy evening, Duan Qingyun accompanied the landlady to deliver cloth, holding an umbrella for her. Upon reaching the cloth shop, he waited outside. Noticing a cosmetics shop nearby, he decided to buy some rouge for her. Just as he was about to buy it, the shopkeeper’s wife emerged after delivering the cloth. Embarrassed, Duan hurriedly followed her out. They went to eat together, and it turned out to be her birthday (delivering the cloth had been merely an excuse; the real purpose was to find an opportunity for them to be alone). Duan dashed out to buy the rouge. The rouge seller had long seen through his intentions and had already wrapped it up, waiting for him. In his haste, Duan collided with a passerby, dropping the rouge. As he bent to retrieve it, Duan Qingyun suddenly noticed his own wanted poster plastered on the opposite wall. He walked away alone. In the rain, the rouge melted into a pool of vivid red on the ground. This image of rouge on the ground is profoundly striking—it signifies both their destined yet unfulfilled connection and foreshadows future peril (like blood).

Late that night, Duan Qingyun hesitated outside the innkeeper’s wife’s door, unsure whether to enter and say farewell. She opened the door, slapped him, and demanded if he intended to leave without a word. “I don’t even know what tomorrow holds,” he said. “What could I possibly give you?” She replied, “I will never regret this.” Then, Duan Qingyun swept the landlady into his arms and carried her into the room. This embrace was truly a passionate one—not only deep in affection and loyalty, but also brimming with heroic spirit. It stood in stark contrast to modern scenes where a groom carries his bride, an act that, though proper and open, often appears petty by comparison.

In the film’s final scene, the landlady walks down the street with a large belly. People whisper nearby: one says, “After all these years of widowhood, how can she be so pregnant?” Another retorts, “Strolling around with that belly—shameful!” Then they wonder, “Who could the father be?” ” Hearing this, the landlady approaches and declares, “This child belongs to Brother Duan Qingyun.” (Duan Qingyun had already died by this point.) The two old women flee in fright.

After watching the film, I suddenly recalled how “Exiled” also ended with everyone dead, leaving only widows and orphans behind. The taste of such endings is different, I suppose.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Bare-Footed Kid 1993 Film Review: Bare feet, shoes, and rouge