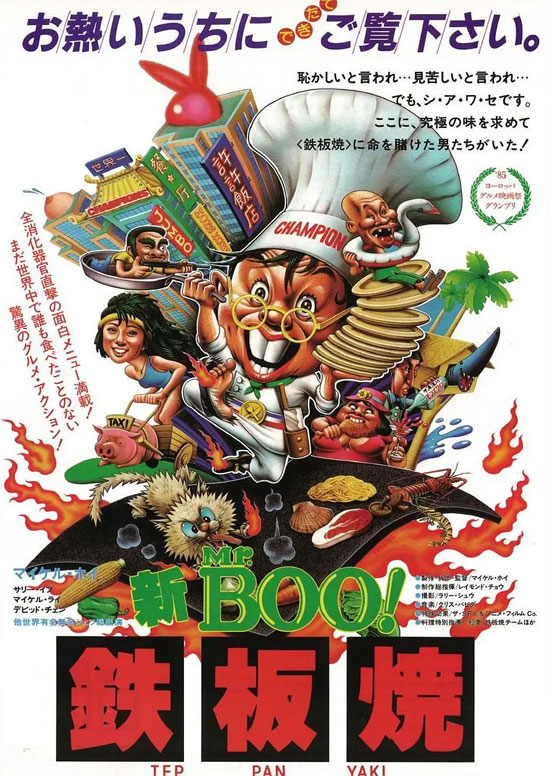

Film Name: 铁板烧 / Teppanyaki / 鐵板燒

It took three years after “Security Unlimited” for this self-written, self-directed, and self-starred new work to be released, revealing the creative pressure Xu Guanwen faced. After all, his younger brother had jumped ship to New Art City, meaning romantic subplots, theme songs, and action sequences would inevitably be scaled back. Moreover, the three “Best Partners” films had dominated the box office for three consecutive years, forcing Xu Guanwen to contemplate how to single-handedly sustain his comedy brand.

Thus, in “Teppanyaki,” his role essentially fused three personas: Siu Koon-man’s understated acting style, the romantic subplots previously handled by Siu Koon-kit (simultaneously breaking the tradition of Sam Hui composing theme songs and scores for the Siu films), and the hapless persona reminiscent of Siu Koon-ying (bullied by his wife, having his eyebrows shaved by his father-in-law). This transformed him into the most pitiable underdog in Siu Koon-man’s films. While comedy remained central, his style and acting approach had significantly evolved.

Another breakthrough was Hui Koon-man’s shift from the “sketch-based” style of his 1970s works to a narrative with a coherent main storyline. Previously, Hsu’s films were essentially collages of standalone gags—a typical approach for television programs. But “Teppanyaki” featured a much clearer and more cohesive narrative, with a more mature structure than his 70s works. Furthermore, elevating the previously peripheral romantic subplot to a central theme (how a timid husband navigates his wife and father-in-law to have an affair) demonstrated Hsu Kuan-wen’s technical growth.

But was “Teppanyaki” a success? Not necessarily. After all, Hsiao had to portray the personalities of both his younger brothers, which made his character feel inconsistent. That wasn’t the main issue, The greater issue lies in his shift from playing sharp-tongued bosses to a bullied man—a transformation audiences clearly found jarring. Its lack of appeal is understandable, especially since no other character truly stands out, leaving the film feeling like a one-man show. It simply lacks the richness of the Hui brothers’ collaborative efforts.

Fortunately, some details still shine, like the climactic hospital showdown between son-in-law and father-in-law, the airplane seat trapping a head and domino effect, the “Only You” gag, and Hsiao Kuan-wen’s tennis match with Lai Siu-tin. Yet the problem persists: the details outshine the plot, perpetuating a recurring flaw in Hsiao’s films.

Hsu Kuan-wen’s creative downturn began as early as 1983’s “The Trail.” That marked his first attempt at crafting a complete genre story and his first venture into a structure where tragedy served as the main plot and comedy as the subplot—a risky endeavor, as one might imagine (hence his decision not to star in it himself, opting instead for producer and screenwriter roles). The result was a box office flop, even under his own banner. “Teppanyaki” made it into the year’s top ten box office hits, yet its critical reception clearly fell short of the Hsu brothers’ collaborative works. Its earnings also lagged a full ten million behind Sam Hsu’s “Aces Go Places III: Our Man from Bond Street” released the same year (even Hsu Kuan-ying joined his brother on this project), leaving it caught between high and low expectations. In 1985 and the first half of 1986, he experimented with acting without directing (“Mr. Boo Meets Pom Pom”) and remaking classics (“Happy Din Don” directly copied 80% of “Some Like It Hot”), but both failed, with box office plummeting below HK$15 million. Fortunately, “Inspector Chocolate” in late 1986 marked a comeback, followed by the critically acclaimed and commercially successful “Chicken and Duck Talk” in 1988. This allowed Sam Hui to smoothly transition into the 1990s and gradually retire from the spotlight.

But perhaps even brothers cannot coexist—two tigers cannot share the same mountain? The year Sam Hui rebounded, his brother Sammo instead hit a slump. The primary reason was altitude sickness while filming “Wai Si-Lei chuen kei” in Nepal. This left him unable to act and suffering from prolonged sluggishness. Consequently, he didn’t appear in any films in 1987 and only made a cameo in his brother’s “Chicken and Duck Talk” in 1988. Wai Si-Lei chuen kei” in Nepal, where he suffered from altitude sickness. For a long time afterward, he was too sluggish to act, let alone perform. Consequently, he didn’t appear in any films in 1987 and only made a cameo in his brother’s 1988 film “Chicken and Duck Talk.” By the time he starred in “Aces Go Places V,” he had lost his former box office appeal. Fortunately, Sam later starred in “Swordsman” and “Front Page.” The former largely restored his form, while the latter revived the “Brothers’ Gang” spirit. Moreover, during Stephen Chow’s peak popularity, the “veteran” Hsu brothers still managed to rake in over 20 million in box office revenue with this film. Consequently, Sam could gradually retire gracefully afterward, with his older brother’s support playing no small part.

In short, “Teppanyaki” stands as both a courageous endeavor and a low point in Sam Hui’s career.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Teppanyaki 1984 Film Review: Hsu Kuan-wen’s Low-Point Work