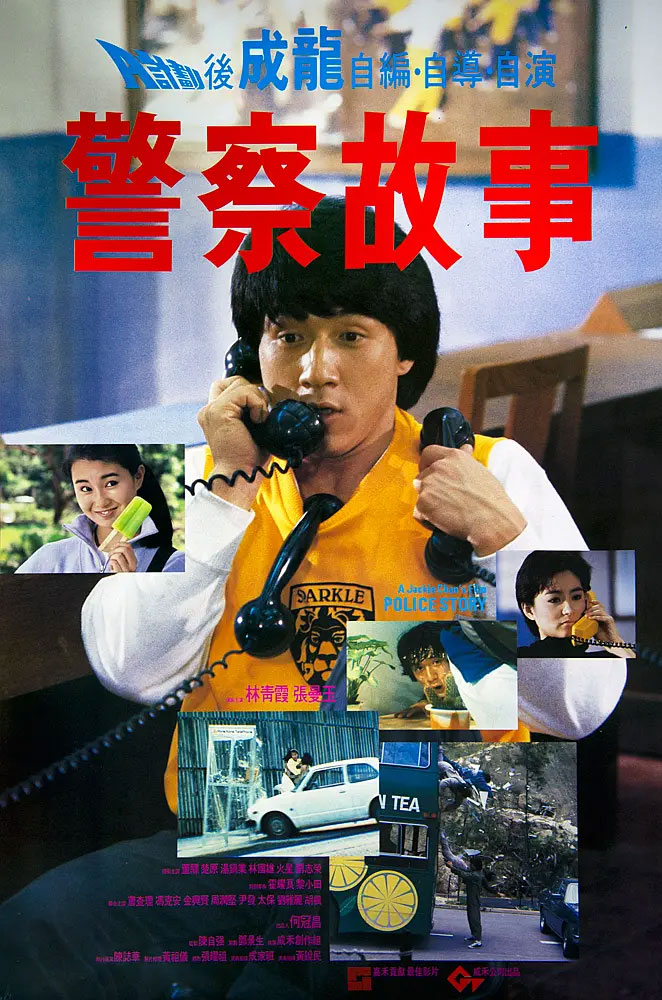

Film Name: 警察故事 / Police Story / Police Force

Looking back at Hong Kong cinema from the 80s and 90s, classics abound, yet few truly deserve the title “remarkable.”

Remarkable because it achieved what others couldn’t.

What did “Police Story” achieve that other films couldn’t?

1. Vivid characters.

For a long time, police officers in Hong Kong films were portrayed as rigid and one-dimensional. They were kind, brave, handsome, sharpshooters, invincible in every battle—in short, too perfect to feel real.

Chan Ka-Kui shattered this idealized police image, restoring officers to their human reality—a revolutionary approach at the time. In the opening slum shootout, cops get shot, scream in pain, wet themselves in fear, and make mistakes. Even Chan Ka-Kui breaks into a nervous sweat amid the hail of bullets.

Colleague Shot

Officers also face financial temptations. When Chen Jiagu apprehended Zhu Tao on the bus, Zhu opened a briefcase and declared, “This money would last you a lifetime.” Later, Officer Wen completely lost his integrity to greed. Police officers also grapple with everyday hardships: meager salaries, retaliation from enemies, and relationship struggles. Ultimately, what drove Chen Jiagu to become a lone hero wasn’t duty—it was being framed and needing to clear his name.

Protecting Witnesses: 32.8 Yuan Daily Allowance

When facing danger, choose courage. When tempted, stay true to yourself. When attacked, fight back. This is down-to-earth heroism. Chan Ka-kui shows us heroes are right beside us—the distance between you and heroism isn’t vast.

2. Meticulous Storytelling

While Hong Kong cinema of the last century produced many masterpieces, it consistently suffered from one flaw: neglecting scripts—that is, neglecting the story itself. Hong Kong cinema of that era mastered Hollywood’s opening sequences and climactic endings, yet failed to learn how to develop a compelling narrative. Even classics like “A Better Tomorrow” and “A Chinese Ghost Story” excelled in their openings and conclusions, but suffered from weak middle acts. This flaw later became a major factor in Hong Kong cinema’s decline.

What makes “Police Story” truly remarkable is its ability to maintain entertainment value and relatability while striving for narrative rigor. Take the courtroom scene where Zhu Tao stands trial: the dialogue is professional and meticulously crafted, earning praise from real-life legal professionals. The portrayal of how Chen Jiaju is framed and gradually becomes a lone hero is equally compelling, unfolding in a way that feels both interconnected and believable.

Driven to desperation, he kidnapped the chief.

3. Innovative combat.

Kung fu films trace their origins to the martial arts sequences in Peking Opera, which were heavily choreographed. Take the series of Wong Fei-hung films directed by Kwan Tak-hing as an example: every strike and block was predetermined, resulting in slow pacing, weak impact, and one word—fake.

Bruce Lee’s films gained popularity precisely because he consciously broke away from these choreographed patterns, advocating a return to real combat—like street fighting—where every move aims to knock the opponent down faster. This made action films feel more authentic and resonated with Western audiences.

But to be fair, Bruce Lee’s films shone only because of his brilliance; supporting characters were often poorly developed. Take the Hongkou Dojo scene in Fist of Fury: dozens of men circling Chen Zhen, merely spinning around, one knocked down only for another to step in—still unrealistic, still fake.

After Bruce Lee’s passing, action films reverted to formulaic choreography. Jackie Chan’s “Snake-Shaped Hand” and “Drunken Monkey in the Tiger’s Eyes” exemplify this trend. However, Chan infused these films with elements of Peking Opera acrobatics, making them visually captivating and allowing audiences to overlook their formulaic nature.

After Bruce Lee, it was Sammo Hung who truly liberated action cinema from choreographed routines and brought it back to real combat. Take the “Five Lucky Stars” series as an example: under Sammo’s leadership, the Hung Gar team minimized the formulaic feel of the moves while maximizing their impact.

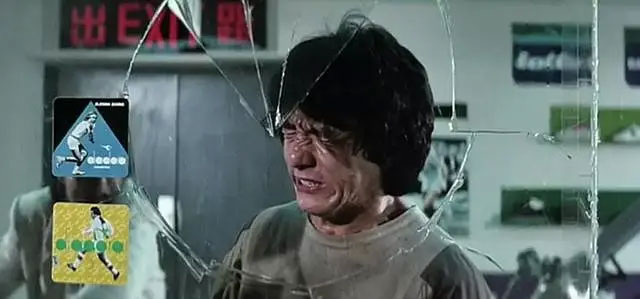

The mall fight shattered countless windows, prompting jokes that Jackie made a movie for the glass.

Building on Sammo’s foundation, Jackie led his stunt team to further enhance realism in “Police Story.” Crucially, he solved a problem dating back to Bruce Lee’s era: how to make a multi-versus-one fight believable? Jackie’s solution was to have the camera follow the actors, framing them only when actively engaged in combat—not constantly circling the action. Anyone familiar with action cinema knows this innovation influenced subsequent action films no less profoundly than the dynamic camera work and rapid editing in The Bourne Identity. In fact, for a long time, Hollywood regarded Police Story as their action film bible. Even Sylvester Stallone admitted that when he lacked inspiration for a movie, watching Jackie Chan’s films would get him back on track.

Jackie Chan visited Sylvester Stallone on set. Stallone raised his hand and told the crew: “This is my idol.”

Moreover, following his death-defying leap from the clock tower in “Project A,” Jackie Chan cemented his reputation as a fearless tough guy in “Police Story” by chasing a bus barehanded and leaping from light poles in a shopping mall.

Vibrant characters, meticulous storytelling, and innovative fight sequences—these are the true reasons why “Police Story” stands as a masterpiece.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Police Story 1985 Film Review: Why is it remarkable?