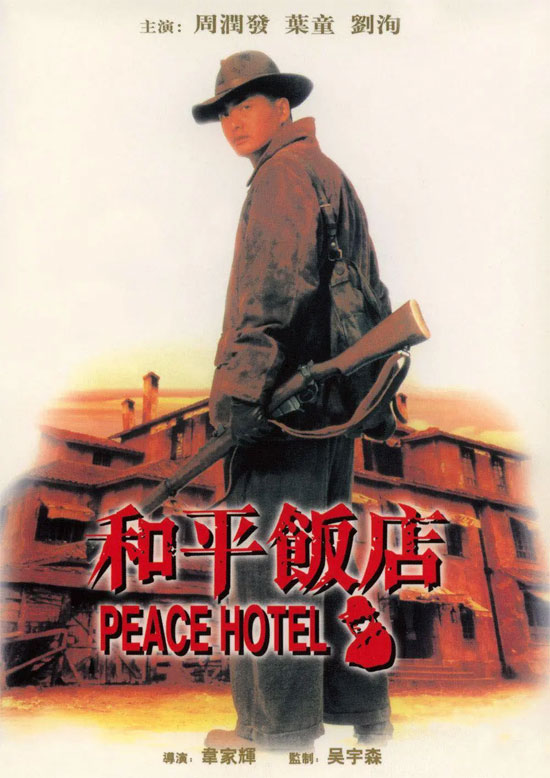

Film Name: 和平饭店 / Peace Hotel / Wo ping fan dim / 和平飯店

An outstanding screenwriter is inevitably a good director. For when he puts pen to paper, he envisions not merely words and narrative, but images. Conversely, a director lacking even basic screenwriting skills can never produce anything worthwhile.

Nearly all of Johnnie To’s films worthy of excellence owe their quality to Wai Ka-fai’s screenplays, with Wai’s name appearing as co-director in the credits. Yet Wai Ka-fai’s own film, “Peace Hotel,” surpasses even all of Johnnie To’s work.

Hong Kong cinema carries a hero complex. Those lone heroes who single-handedly turn the tide, one against a hundred, may be scorned by realists. Yet the genuine emotion and impact they generate within pure fiction are truly delightful.

I firmly believe Wai Kar-wai is no realist. He is the finest storyteller among all storytellers, his compelling narratives rooted in the world within his heart. They carry his unique literary sensibility—perhaps dreams, perhaps legends, perhaps sighs of metaphor.

Ten years ago, on a colorless night under a moonless sky, the demonic bald-headed killer slaughtered all his brothers. The white dove became a symbol, the blinding light a focus. That single moment of eye contact was enough to purify a soul. Always believe in the power of sudden enlightenment—”lay down the butcher’s knife and become a Buddha” is never mere empty talk.

From then on, the Killer King planted his flag, guarding a sanctuary in a chaotic world, offering a space for survival to those with nowhere else to turn. A killer opening a Peace Hotel might seem the ultimate self-deception and lie to others, yet who could truly comprehend the desolate yearning for peace within this battle-scarred soul?

Ten years of peace shattered by a woman. Ten years ago, slaughter began because of a woman; ten years later, it ended the same way. In a man’s world, women are always the reason for killing. More crucially, men willingly kill for women. The greater the hero, the truer this is. Especially when it’s a meticulously laid trap.

Human hearts are treacherous, especially those at the Peace Hotel—all of them utterly depraved and madly afraid of death. If you don’t send someone away, everyone can die together in a blaze of glory. But send one person away, and you become a traitor to all. Your greatness, your kindness—they take it for granted, as if it were their due. Yet make one wrong move, and your greatness vanishes into thin air. All that talk about heroes being victims of tragic times is a vicious lie. The tragedy of heroes stems from the wickedness of the human heart—it has nothing to do with the times.

The three blind men, unable to see this world, were not blinded by illusions. Their hearts were clearer and braver than others. Yet in the end, even the blind lost their courage and surrendered in panic. Heroes, after all, are forever alone.

With the King of Killers dead, the Peace Hotel could no longer exist. After ten years of peaceful life, leaving the sanctuary to re-enter the martial world, death was inevitable. At least our hero, in death, possessed a beautiful love.

The voice-over at the end becomes Wai Ka-fai’s idealistic elegy for this world steeped in slaughter.

The entire world is consumed by killing—struggling, scheming, fighting to the death. How could you possibly save humanity and carve out a pure land in this world?

Peace? As long as man remains, it’s but a laughable notion.

Looking back at this 1995 film all these years later, it has inevitably become a symbol. A symbol marking the end of Hong Kong’s golden age of heroic cinema. The King of Killers drenched the Peace Hotel in blood; the hero died, the Peace Hotel collapsed—and Hong Kong cinema, too, died.

After this, perhaps John Woo’s white dove brought some fresh air to Hollywood. But when he returned to his native tongue, “Red Cliff” ultimately couldn’t escape the fate of China’s uniquely “terrible period dramas.”

Tsui Hark’s “Seven Swords” still retained a modicum of dignity, but by “Missing,” it had become a dud.

Perhaps the iron triangle of Wai Ka-fai, Yau Nai-hei, and Johnnie To still delivers films that compel you to ponder deeper questions. Perhaps Peter Chan persists in quietly crafting works that are both visually compelling and artistically sound. Perhaps Pang Ho-cheung continues his intellectual scrutiny of Hong Kong and the world with unrelenting anxiety. Beyond these few, Hong Kong cinema seems bereft of others.

This is the era we live in—an era where seeing “Infernal Affairs” should be enough to console ourselves that we ask for nothing more.

Hong Kong, this magnificent island that both perfectly inherited Chinese traditions and embraced nearly a century of intense collision with Western culture, this region with the world’s highest density of great actors—how the hell can you make sense of its film industry being in such a predicament?

Whether it’s resentment or resignation, the heroic era has passed. All we can do now is preserve a memory in legend. “Though I saw our friend leave me that day, I still hope one of these rumors might be true.”

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Peace Hotel 1995 Film Review: 1995,The Last Heroic Era of Hong Kong