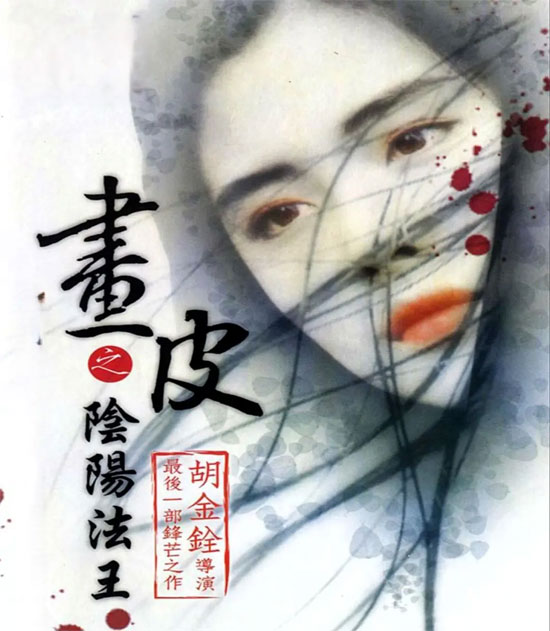

Film Name: 画皮之阴阳法王 / Painted Skin

The first time I saw “Painted Skin,” it was probably on some satellite channel or movie station back then. The picture quality was abysmal, and you couldn’t make out the dialogue without cranking up the volume. In those days, we were still more amazed and impressed by flying-fist action films like “Swordsman 2” and “Swordsman 3.” Moreover, with “A Chinese Ghost Story” setting such a high standard, this film inevitably drew criticism. It was seen as one of the weaker entries in Joey Wong’s ghostly repertoire. Compared to the “Swordsman” trilogy, the fight scenes here felt clumsy, especially with the Taoist brothers’ feeble magical powers and lackluster special effects. It felt nothing like a Hong Kong or Taiwanese film—more like a mainland Chinese production.

Yet twenty years later, having watched most Hong Kong films across eras, Japanese swordplay epics, Westerns, and various Western genre films, I could only pass the time with Shaw Brothers films from the 60s to the 90s. It was during this period that I encountered wuxia and kung fu films by great directors like Chang Cheh and Tsui Hark. Among them, the films directed by the legendary King Hu for Shaw Brothers—Sons of Good Earth and Come Drink with Me, especially Come Drink with Me—stood out as uniquely special within the vast catalog of Shaw wuxia films. This sparked my conscious pursuit of Hu King-chuan’s films. How fortunate I was to discover works like Sons of Good Earth, Come Drink with Me, Dragon Gate Inn, A Touch of Zen, The Fate of Lee Khan, The Wheel of Life (First Life), “Legend of the Mountain,” “Raining in the Mountain,” ‘Anger’ from “Four Moods,” “The Valiant Ones,” and “All The King’s Men.” Remarkably, whether it’s most Shaw Brothers productions or the master director’s own works, I’ve been privileged to experience them for the first time in Blu-ray quality. It would be a profound misfortune to experience the master’s films without the cinema experience or Blu-ray quality. Over two decades of viewing experience have allowed me to revisit and re-evaluate the works of Master King Hu.

At some point, we grew weary of the protagonist’s aura, tired of the inevitability that the hero would crush the villain from start to finish. We’ve grown weary of wire-fu stunts, freeze-frame fight sequences, and even the most spectacular choreographed combat. More profoundly, we’ve grown tired of costumes, sets, and props that cling to outdated cinematic styles. We’re weary of bombastic BGM and dialogue that sounds like it belongs in a modern-day drama.

It is no exaggeration to say that when it comes to period films, Hu Jinquan stands alone. Telling a compelling story, crafting immersive narratives, achieving outstanding cinematography, and delivering breathtaking editing—selecting the right actors is the entire mission of a great director. Yet looking back over the past century of Chinese directors, if we assume none of them possessed the ability to “burn through budgets,” it’s safe to say that if Hu Jinquan dared claim second place, no one else would dare claim first.

In the 1990s, “Swordsman” and “New Dragon Gate Inn” reignited the public’s passion for wuxia films. Yet we all know “Swordsman” bore King Hu’s name as director, though beyond its foundational premise, it bore little resemblance to his work. Tsui Hark spent years studying King Hu’s work. Though he could capture the surface, not the essence, he still launched a new wave of wuxia cinema. “New Dragon Gate Inn” largely followed King Hu’s foundational wuxia framework, but with ample funding and the expertise of an action choreographer, it successfully captivated audiences. It stands as an unparalleled monument within the New Wave of Chinese Wuxia. What distinguishes “Dragon Gate Inn” from “New Dragon Gate Inn”? The difference likely lies in the commercial film’s ability to captivate audiences.

When I revisit “Fairy Ghost Vixen,” Hu Jinquan’s cinematic imagery still floods my mind. Even after finishing Jin Yong’s novella “The Return of the Sword Lady Riding West on White,” Hu Jinquan’s visual style remains vividly present. It’s a pity the great director never had the chance to truly adapt one of Jin Yong’s martial arts epics. I often wonder: had “Swordsman” been filmed in King Hu’s style, its achievement might have far surpassed Tsui Hark’s wuxia films. And wouldn’t “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” have reached an even higher realm?

Though much of the above has little to do with “Painted Skin,” it is precisely this journey of reflection that allows me to revisit this profoundly underrated masterpiece. In 1992, the film was shot on location in mainland China, employing local extras and Mandarin dubbing. Yet its pivotal scenes retain Hu Jinquan’s timeless literati sensibility and signature meticulousness:

The scholar Wang Sheng, perpetually lingering in pleasure quarters; the female ghost You Feng; and the Taoist priests portrayed by Liu Xun and Wu Ma. These characters are vivid screen incarnations of Pu Songling’s “Fairy Ghost Vixen.” Not a single line of dialogue feels superfluous, as the narrative unfolds with perfect pacing. In retrospect, this film marked a breakthrough for all three leads—Bibi Wang, Sammo Hung, and Aaron Kwok—yet it remains quintessentially Kwan’s cinematic universe. Many praise the first half of “Painted Skin” for its vivid portrayal of street life, while criticizing the pacing of the latter half—the search for the Taoist Master Taiyi and the climactic battle against the Yin-Yang Dharma King. Yet, viewed as a whole, the narrative’s structure is perfectly calibrated; not a single element could be added or removed.

King Hu’s films possess a profoundly personal style. Yet this very style laid the foundational framework for the entire wuxia genre. In 2000, Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” won the Academy Award, yet beneath its surface, one could still discern the skeletal structure established by King Hu over thirty years prior.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Painted Skin 1992 Film Review: Revisiting a Severely Underrated Masterpiece 20 Years Later