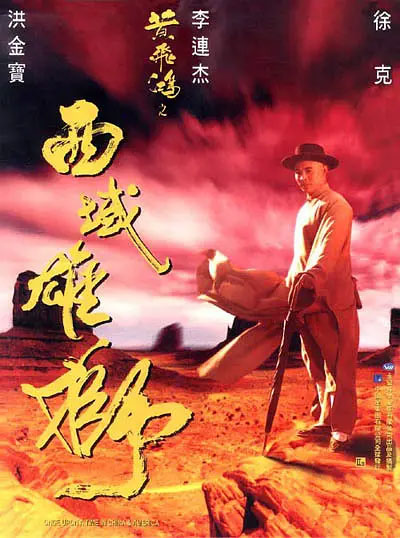

Film Name: 黄飞鸿之六西域雄狮 / Once Upon a Time in China and America / 黃飛鴻之西域雄獅

The sixth installment, The Lion of the West, may not be highly regarded by many and has even been criticized as incoherent, but I personally found it quite enjoyable. Even with Sammo Hung taking over as director, it maintained the consistency of Tsui Hark’s wuxia-style Wong Fei-hung series.

First off, I don’t consider this series (1. The Legend of the Dragon, 2. The Legend of the Dragon II, 3. The Legend of the Dragon III: The Lion King, 4. The Legend of the Dragon IV: The Legend of the Dragon, 5. The Legend of the Dragon V: The Legend of the Dragon, 6. The Legend of the Dragon VI: The Lion King of the West) to belong to Jet Li. The two films starring Zhao Wenzhuo are equally brilliant. Nor does this series truly belong to Wong Fei-hung. Wong Fei-hung’s film franchise had already achieved fame long before this series, with the most renowned being the version directed by Kwan Tak-hing. Additionally, many other actors have portrayed Wong Fei-hung in equally compelling performances. This particular series represents Tsui Hark’s unique wuxia interpretation of Wong Fei-hung.

Tsui Hark has always been renowned for his wuxia films. To my recollection, he hasn’t directed many kung fu movies and likely isn’t particularly skilled in that genre. Thus, he adapted Wong Fei-hung into a wuxia figure, embracing Jin Yong’s philosophy that the greatest heroes serve their country and its people. He integrated Wong Fei-hung’s deeds into modern Chinese history, crafting him into a national hero.

The first film, The Legend of Wong Fei-hung: The Sky’s the Limit, opens with Wong Fei-hung discussing state affairs alongside Black Flag Army leader Liu Yongfu. This immediately places Wong Fei-hung within the pages of history books. He is even gifted a folding fan inscribed with an unequal treaty. Later, this fan is damaged in a fire, transforming into an inscription of an equal treaty—a rather clever touch. After the opening credits, scenes shift between a bustling teahouse filled with leisurely Qing citizens and chaotic streets where soldiers escort prisoners, Westerners stroll, missionaries preach, and Buddhist monks wander bewildered. The Hallelujah chorus competes with the street clamor, only to be drowned out by the thunderous steam of a steamship. In just two minutes, a few simple shots establish the historical backdrop, vividly depicting late Qing society. This contrasts with the opening’s textbook-like feel yet complements it perfectly. The subsequent appearance of foreign concessions and leaflets advertising passage to Gold Mountain (the United States) on the streets likely signaled this installment’s theme: Chinese people, too, had endured the same fate as Black people, being sold into slavery. Viewed within the entire series, this episode primarily establishes the backdrop, then uses the Shandong martial arts master Yan Zhendong and his Iron Shirt technique to illustrate the obsolescence of traditional martial arts in that era.

The second film, The Legend of Wong Fei-hung: A Man Should Stand Tall, is widely regarded as the best in the series. The opening scene features the White Lotus Society performing occult rituals, smearing burning incense sticks on their bodies like removing body hair, attempting to shield themselves from Western firearms with their flesh. They burn pianos, clocks, and other Western goods—even a cute spotted dog. Later scenes, such as Master Wong riding a train, denouncing Li Hongzhang on Guangzhou streets, and Auntie Thirteen being called a “fake foreign devil,” serve to establish the historical backdrop much like the first film. At a Sino-Western medicine symposium, Master Wong astonishes foreigners with his divine skills, with Sun Yat-sen serving as interpreter—leading to their acquaintance. They’re soon ambushed by the White Lotus Society, where a foreign doctor is shot dead on the spot. This makes the foreign ambassador’s earlier complaint to Qing officials—”We foreigners face grave danger in China”—seem all too justified. Donnie Yen’s character inevitably engages in some slippery behavior, but we’ll spare the details. Two boss battles stand out: Master Wong’s decisive defeat of the White Lotus Society and his furious slaughter of Qing ministers to protect revolutionaries, clearly establishing this installment’s theme. Yet the true highlight remains Donnie Yen’s cloth staff.

The third installment, The Legend of the Dragon, opens with the appearance of Empress Dowager Cixi and representatives of the Eight-Nation Alliance dressed in Tang-style attire. The train sequence returns, shifting the stage from Guangdong to Beijing. This time, the lion dance truly takes center stage. As for Tsui Hark’s allegiance in the Russo-Japanese rivalry, let’s set that aside. This installment shines with Xiong Xinxin’s Ghost Foot Seven and Master Wong’s Auntie Thirteen doling out sweet moments for the single folks. Plus, Mo Shao-tsung’s Liang Kuan—though a little rascal—is just too adorable.

Part IV: The Legend of Wong Fei-hung: The King’s Style. Blaming the decline in quality solely on Zhao Wenzhuo’s inferiority to Jet Li is unfair. Not only did the lead change, but the director did too. Many plot devices were recycled from earlier installments, and the storyline felt more like a supplement to the previous film, with lion dancing still carrying the weight. The clash between traditional religion and Christianity intensifies—or rather, traditional superstition grows increasingly sinister, while the priest remains steadfastly virtuous. From this installment onward, Master Wong’s romantic prospects flourish, though Jet Li’s character misses out. Auntie Fourteen, replacing Auntie Thirteen, publishes a newspaper advocating women’s rights, but Master Wong dismisses it. Other martial artists are illiterate, unable to read a single word. The Red Lantern Society, masquerading as the White Lotus Sect, commits atrocities under the banner of “Support the Qing, Exterminate the Foreigners.” Meanwhile, the anti-Qing, pro-Ming faction led by Chin Kar-lok and Billy Chow has become outright lackeys for the foreigners. The opposition between the two sides is starkly defined. Of course, as we all learned in history class, both sides ultimately failed. The Eight-Nation Alliance prevailed, the Empress Dowager fled, and a disillusioned Master Wong had no choice but to return south.

Part Five: The Dragon City’s Villain. Many claim this installment lost its flavor, but I adore it. Tsui Hark returned to directing, and Master Wong’s journey south remained rooted in late Qing history. The backdrop—merchants hoarding grain, corrupt officials, rampant banditry—directly continued from the previous film’s conclusion in southern China. Yet newspapers claimed the south thrived, prompting Master Wong to quip that literacy had become utterly useless. Who says this series must stick to the flavor of the first three films? What’s the point without change? Should it just keep recycling old tropes like the previous installment? Master Wong picking up a gun to take on pirates strikes me as a bold and daring creative choice. His romantic luck remains intact, with two aunts vying for his attention in adorably fierce competition. Ah Su is no longer just a translator; his sharpshooter role finally gives him action scenes. The ending, where two imperial factions take over local government offices, continues to reflect late Qing history. Also, how did the Father of the Nation end up as a constable?

The sixth installment, Wong Fei-hung: The Lion of the West, leaves China and adopts a Western-style aesthetic, yet remains closely tied to modern Chinese history—this time chronicling the struggles of overseas Chinese. Directed by Sammo Hung with Jet Li returning as lead, the production gap of several years between films resulted in looser narrative continuity. Even when fighting alongside cowboys in America, Ah Su and Ah Qi didn’t continue their gunplay—a bit of a letdown. Auntie Thirteen, however, even mastered the Shadowless Kick. (laugh)

Overall, aside from the fourth and final installments—directed by others—which are slightly weaker, I’d give the entire series five stars. This remarkable franchise masterfully blends kung fu, wuxia, and Western genres, offering both profound reflections on ethnicity, history, nation, and individuality, while remaining thoroughly entertaining.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Once Upon a Time in China and America 1997 Film Review: The final installment of Tsui Hark’s Wong Fei-hung martial arts series