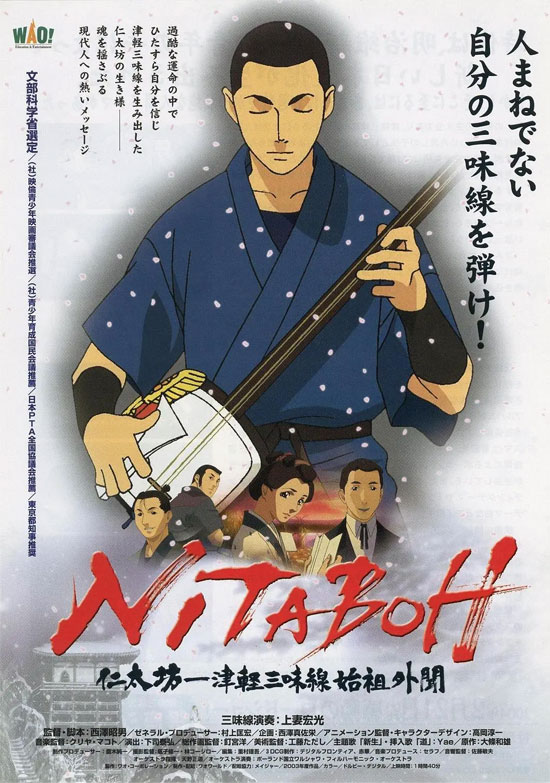

Film Name: 仁太坊:津轻三味线始祖外传 / Nitaboh: Tsugaru shamisen shiso gaibun / Nitaboh

(I)

I’d like to recommend a Japanese animated film to everyone: “Nitaboh: Tsugaru Shamisen Shiso Gaibun.”

If I recall correctly, this should be the second animated film officially recommended by this site to our readers. The first was “Jiro and Miu,” recommended to students studying animation—a stop-motion graduation project created by European animation students. Though its techniques and craftsmanship aren’t quite masterful, it possesses a distinctly rich animation flavor. Particularly in its narrative structure, I believe it offers significant inspiration for Chinese students.

This recommended film, “Nitaboh: Tsugaru Shamisen Shiso Gaibun,” isn’t a masterpiece by a renowned master either, but rather a relatively realistic animated feature. Personally, I’m not a fan of animation tackling realistic themes. Films like “Jin Roh: The Wolf Brigade” work well as movies, but as animations, they always feel like they’re missing something. “Nitaboh: Tsugaru Shamisen Shiso Gaibun” suffers from the same issue. So why recommend it? Because I believe this film uniquely reflects the Japanese perspective on life, values, and existence. As someone who recently returned from Japan, I deeply feel that this film penetrates to the core of the Japanese psyche and spirit. Watching this one film yields far greater insight than watching a hundred Hollywood animated blockbusters.

The shamisen is a traditional Japanese stringed instrument, said to have evolved from the Chinese sanxian. Professional performers emerged in the 15th and 16th centuries, making it a relatively young instrument in terms of history. Tsugaru is a region in Japan, located in Aomori Prefecture at the northernmost tip of Honshu. Due to its distance from Tokyo and Kyoto, even during turbulent times like the Meiji Restoration, the people there enjoyed relative peace and stability. However, its isolation from political and cultural centers also meant the people lived in relative poverty. In this region lacking entertainment, folk music like the shamisen flourished as one of the few cultural activities, and people cherished its performances.

Nita-bou, originally named Jintaro Akimoto, lost his mother at a young age. At eight, he went blind from smallpox, and later his father drowned in a river. From childhood, he displayed exceptional musical sensitivity, enjoying playing the flute and shakuhachi. By chance, he heard a shamisen performance by a courtesan from the Yun’yu district and resolutely sought her as his teacher. When he began performing door-to-door in villages, his music was initially met with rejection, but gradually attracted listeners. His catchphrase was, “I am not begging for food; I am an artist.” As the progenitor of the Tsugaru shamisen style, he revolutionized the instrument’s playing techniques, achieving nationwide fame by age 24. This animated film recounts the story of Nitaibō.

I believe the most quintessentially Japanese aspect of the film lies in its revelation of a national spirit—the pursuit of truth. In fact, I believe Japan’s remarkable achievements—despite being a small island nation—its swift transformation during Western invasions, and its rapid post-war recovery from utter devastation—all stem from this “pursuit of the Way.” It means striving for perfection in everything they do. What defines this “best”? It means grasping the underlying principles and true essence of any endeavor. Calligraphy, flower arrangement, tea ceremony, bushido—every Japanese pursuit has its own “way.” Take the samurai, for instance: to hone their martial arts and physical prowess, they would literally meditate naked atop snow-capped mountains during the harshest winter days. This state of selfless devotion to the pursuit of truth has shaped the character of modern Japan and its people.

It must be noted here that the reason Japanese animation achieves such excellence lies in this spirit of pursuing perfection. From directors and producers to sound engineers and voice actors, every professional in Japan’s animation industry approaches their work with this very spirit. During the explosive growth of Japanese animation in the 1960s and 1970s, the Japanese government actually implemented no policies to encourage animation development. Manga artists held a low social status, widely regarded as unproductive. Yet even in this environment, a group of individuals strove tirelessly for their ideals. This is the essence that built Japanese animation’s current stature, and it represents the greatest gap between Chinese and Japanese animation.

This film embodies this spirit of pursuit from its surface to its core. In content, Jintaro seeks the way of the shamisen; in production, every background is a faithful recreation of scenes sketched on location by the team. This unity of form and substance elevates the film!

I particularly want to highlight several supporting characters, starting with Jintaro’s close friend Kikunosuke. He embodies the most vibrant aspect of Japan during the Meiji Restoration: an eager, insatiable thirst for learning Western advancements. His character reflects why Japan could forge its path of reform—because it had young people like him: daring to act and speak, driven by ideals and a relentless pursuit of truth. Another group, or more accurately, a collective of supporting characters, are the women in the film. This work captures all the admirable qualities of Japanese women—tenderness, compassion, restraint, and more.

This animated film truly deserves its recommendation by Japan’s Ministry of Education. I believe Japanese students who watch it will gain a deeper appreciation for Japanese culture and the resilient spirit embodied by its renowned figures. In contrast, what kind of films does our State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television recommend? How can films that fail to achieve unity between form and content truly move the heart?

(II)

CCTV6 aired the Japanese animation “Nitaboh: Tsugaru Shamisen Shiso Gaibun.” This reignited my interest in the film. I revisited the final eight minutes—the shamisen showdown that left the deepest impression during my first viewing—and unexpectedly shed tears once more. This is a classic sequence that can move you profoundly even when viewed in isolation.

Allow me to briefly analyze this segment.

It primarily consists of two parts: Tawarabo’s performance from 86:45 to 89:11, followed by the climactic finale of Nita-bou’s performance from 89:30 to 93:35. Audience reactions are interwoven throughout, with scenes depicting the crowd before and after the performances. Naturally, the film concludes immediately after Nintaifang’s performance, amidst the crowd’s ecstatic cheers.

Tawarabo possesses consummate skill. His performance is dazzlingly elegant, his technique perfectly complementing the regal peonies adorning the screen behind him. The audience gazes in admiration. Yet, beside him, not a single petal falls from the enormous cherry tree in full bloom. Throughout the nearly three-minute performance, the camera repeatedly zooms in on his hands. This serves as both a testament to the confidence of Japanese animation—where character movements are highly realistic—and a highlight of Tawarabo’s fluid mastery of traditional shamisen techniques.

Following such a brilliant performance, the audience immediately responded with thunderous applause, with some even chanting “Japan’s number one!” This unspoken pressure weighed heavily on Nitaibo, who was about to take the stage next. Of course, perhaps only those concerned for Nitaibo sensed this pressure; Nitaibo himself remained remarkably calm. For at that moment, he had entered a new realm.

The moment Nintaifang began plucking the strings, the entire hall fell silent. His opening passage seemed unadorned, lacking profound technique, and played at a pace considerably slower than Tawarabo’s. Concerned expressions flashed across the faces of those watching him. Seated nearby, Tawarabo wore a stern expression, as if scrutinizing every detail, yet felt no pressure. He believed Nintaifang could not possibly surpass him with such a performance. Yet no one realized this was merely the prelude and foundation for Nintaifang to elevate his own artistry to its pinnacle.

The 90-minute, 10-second mark proved pivotal. A single cherry blossom petal drifted slowly before Nintaifang. Though blind, he furrowed his brow as if sensing it. His hand trembled, and the melody shifted—a wholly new shamisen composition never before played. As Nintaifang plucked the strings, more and more cherry blossom petals drifted down. He was now fully immersed, becoming one with the cherry tree beside him. We know the cherry blossom is a symbol of Japan, representing both the spirit of Bushido and the land, its people, and everything that defines Japan. At this moment, sensitive listeners could feel this essence within his music. This resonance transcended mere shamisen technique, rising to a shared identification born of a common love for Japan. Nintaifang touched the true, hidden emotions within each person’s heart.

The camera zoomed in on Nita-bou’s left and right hands, while cherry blossom petals continued to drift down. Beside him, Tawarabo grew restless. He sensed the pressure from Nita-bou’s new musical form, and more profoundly, the purity with which Nita-bou composed Japanese shamisen music from a crystalline heart. His hands unconsciously clenched his clothes. Yet Nintaifang kept playing. His music carried people to jungles, to village cottages, to the snow-covered northern lands of Japan, to the golden rapeseed fields of Aomori, to the breathtaking sunset, to the diligent men, women, and children working with heart, to the surging sea, to the majestic, towering snow-capped mountains… One by one, the seated audience rose involuntarily to listen—to hear the sounds of their homeland, to heed the call from their very souls. Cherry blossom petals drifted down like rain.

Tawarabo no longer felt conflicted. He was utterly moved by Nintaifang’s voice. As a competitor, he too offered a knowing smile at his rival’s performance. In this moment, he was utterly immersed in Nintaifang’s melody. The old grandmother closed her eyes in prayer, those who cared for Nintaifang shed tears of warmth, and faces of all ages radiated a happiness that sprang from the heart. If Tawarabo’s music was meant for appreciation, then Nintaifang’s stirred profound emotion from within. After the final string note of Nitaibang faded, the hall remained in profound silence. Only after a long pause did thunderous applause erupt—everyone was still utterly captivated by the music.

This is what I felt from this eight-minute film. It brims with the power of detail; it uses the subtle shifts on the audience’s faces to illustrate the moving essence of Nitaibang’s music; It uses scenes from everyday life, seemingly unrelated to the performance, to show how Nitaifang’s music resonates with people’s lives; it uses a cherry blossom tree to convey Nitaifang’s and the entire audience’s love for Japan—the very foundation of his ability to create such profoundly moving music.

We have reason to believe this piece by Nintai was entirely improvised. From the moment he took the stage, he contemplated how to express his music and what emotions to infuse within it—unlike Tawarabo, who focused solely on defeating his rival and becoming Japan’s best. At the beginning of his performance, he hadn’t fully grasped what he wanted to express. It wasn’t until he felt that cherry blossom petal fall that he realized this was it—his love for Japan, for this land and the people who toil upon it. He would dedicate his music to these people and this nation.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Nitaboh: Tsugaru shamisen shiso gaibun 2004 Film Review: Experience Japan’s Spirit of Seeking Truth