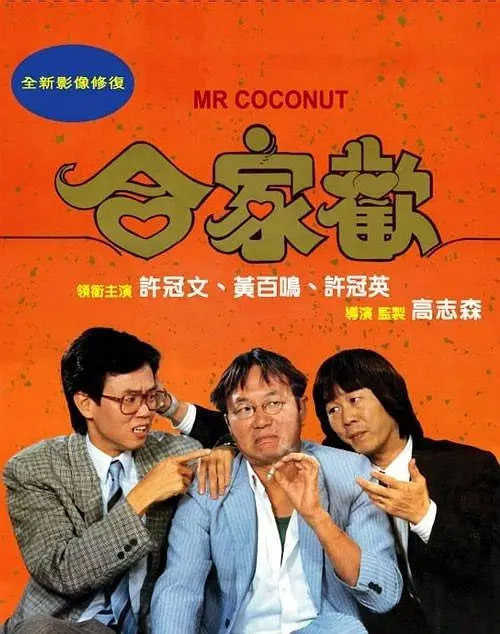

Film Name: 合家欢 / Mr. Coconut / 合家歡

While reading film reviews, I noticed most focused on the complex relationship between Hong Kong and mainland Chinese at the time—whether it was intolerable discrimination or Hong Kongers’ fears surrounding the 1997 handover. In truth, this is merely the era’s imprint reflected through the film’s specific comedic framework, tailored to its time. It wasn’t the film’s core focus. Besides, Hong Kong cinema back then was primarily driven by box office success, and it’s doubtful there was any deliberate intent to reflect cultural ideology.

That said, the way Hong Kongers viewed mainlanders back then might resemble how mainland cities now look at rural areas. Though I haven’t experienced Hong Kong of that era, the urban-rural divide in mainland China after reform and opening up remains deeply striking. In the film, the clash between Sam Hui—the sole mainland representative—and the civilized Hong Kongers epitomized by Raymond Wong is most evident in their debate over spitting culture.

Ranting About Spittoons at International Conferences

In the subsequent perception of mainland Chinese, the spitting culture was also uniquely distinctive. However, in the film, while this conflict is evident, it primarily plays on cultural habits and differences to create humor. Audiences needn’t be overly sensitive, as the portrayal of Sam Hui is largely positive. Conversely, the film subtly satirizes Hong Kongers’ mercenary and profit-driven tendencies. This extends beyond the petty man archetype embodied by Raymond Wong to encompass Hong Kong variety shows and insurance companies, none of which are portrayed in a favorable light.

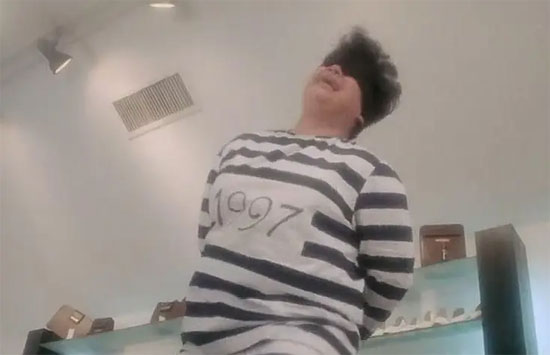

The depiction of the 1997 handover is most starkly illustrated by the scene where Maria, wearing a prison uniform emblazoned with “1997,” is executed by firing squad.

Maria’s prison uniform bears the year 1997

This starkly reflects Hong Kongers’ fear of the handover. Another scene shows Yang Fan’s character, a father, dining with his son at a buffet when they encounter Alan Hsu washing apples in a urinal. His immediate decision to emigrate further underscores Hong Kongers’ anxiety about mainland assimilation post-1997. This recalls the scene in “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World” where Uncle Biao, during a dinner with friends and family, is asked about emigrating and spouts patriotic rhetoric about loving China—only to reveal that poverty is truly blocking his path (though in the sequel, Uncle Biao’s family does emigrate). This illustrates that such sentiments genuinely existed among Hong Kong people at the time.

Returning to the film itself, it stands as a rare gem among Hui’s comedies. Compared to his earlier directorial efforts, this work feels more polished—or perhaps more formulaic. The film opens with rapid-fire vignettes introducing the two main characters—Hsu Kuan-wen and Wong Bak-ming’s family—before intertwining their stories through a family visitation letter. The ensuing cultural clashes between the two groups, from family dynamics to the self-service restaurant, deliver nonstop laughs.

Hsu Kuan-wen’s acting is undeniably nuanced. In the rural scenes, he genuinely carries a whole pack of cigarettes wedged under his shoulder strap.

The narrative swiftly shifts to the main plot: Hsu goes for a job interview, fails miserably, faces family disapproval, enters a TV contest to win a trip, and ultimately triggers the climax. The story flows seamlessly, each element interlocking perfectly—a clear testament to Ko Chi-sum’s directorial prowess. This narrative strength is notably more pronounced here than in Hsu’s earlier works. The most memorable climactic scene is undoubtedly the classic sequence where Hsu, returning from Africa, encounters the entire cast in the dead of night.

Given the setup from the previous week, this segment is both logical and hilarious.

The black guy here is indeed cross-server chatting.

Such scenes are indeed commonplace in Stephen Chow’s own films, which is why he’s regarded as the godfather of Hong Kong comedy. The film’s ending is slightly disappointing. While the decision to uphold justice by forfeiting the insurance money is morally sound, it feels abrupt given the earlier setup where the daughter deceived her father for money. The climax involving catching a pervert on the subway does have foreshadowing, but it lacks sufficient impact.

Overall, this film is truly outstanding, standing apart from other high-scoring comedies. Hsiao Kuan-wen’s acting is nothing short of masterful. Unlike his previous portrayals of stingy bosses in films like The Private Eyes, Security Unlimited, and Chicken and Duck Talk, he perfectly captures the uncultured, coarse, and rustic nature of the mainland fisherman this time, without any sense of incongruity. Wong Bak-ming also shines with his talent, making his portrayal of the insecure little man deeply memorable and laying the groundwork for his later roles. At the time, I was surprised to see Joey Wong in a minor role, but looking back now, I realize that minor role was actually quite significant.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Mr. Coconut 1989 Film Review: The Classic Clash of Hsü Kuan-wen and Wong Pak-ming