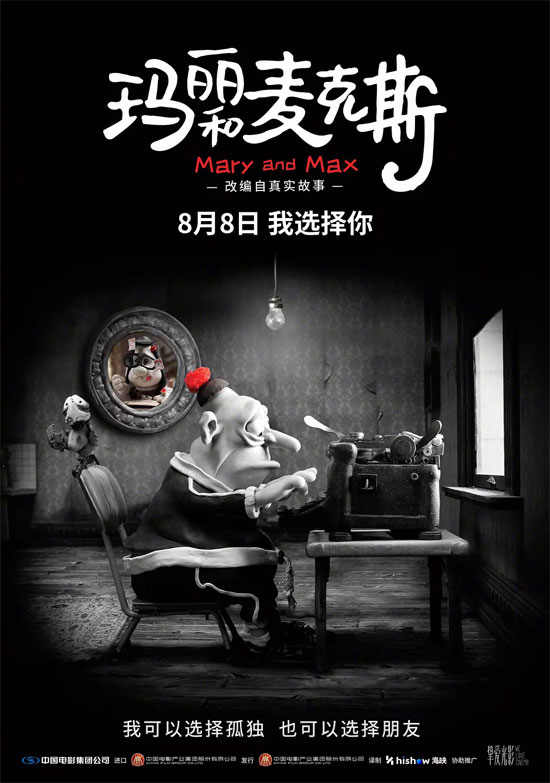

Film Name: 玛丽和麦克斯 / Mary and Max

Although “Harvie Krumpet” was Australian stop-motion director Adam Elliot’s fourth film, it was the first to bring him widespread recognition. Many audiences discovered this Oscar-winning Best Animated Short Film, which showcased the director’s distinctive narrative style and unwavering dedication to clay animation. In 2009, Adam Elliot released his first clay animation feature film, “Mary and Max,” which garnered major awards at numerous world-class animation festivals, including Annecy and Ottawa.

Five years passed between Harvie and Max. In what ways did Adam Elliot’s films remain consistent, and in what ways did they evolve? What principles does he rigorously uphold, and where does he boldly innovate? This is what this article seeks to explore.

I. The Evolution and Continuity of Film Form

From Harvey to Max, Adam Elliot’s greatest commitment—and perhaps his lifelong dedication—lies in the medium itself: clay animation. Much like Hayao Miyazaki’s devotion to 2D animation, Adam possesses an unwavering passion for stop-motion clay animation. This dedication is particularly remarkable in today’s world dominated by American 3D animation. Adam possesses no technical expertise in computer animation, yet his path to clay animation wasn’t born out of necessity; rather, it stemmed from his deep affection for the medium, leading him to consciously reject the pursuit of trendy CG technology.

So what exactly draws Adam to clay animation? It’s the sense of authenticity. In an interview, he once stated: “I believe my job is to strive for believability—even with clay figures, making them as credible as possible. These characters are real, just occasionally rendered as clay figures. Much animation, especially computer-generated, feels overly regulated, rigid, and predictable. While digital tools can create many effects, stop-motion animation still possesses its own magic. When audiences see the fingerprints on a clay figure, they know what they’re seeing is real, not computer-generated.” In Adam’s films, there is absolutely no CG. Every scene, character, and prop exists tangibly, and every shot is captured frame by frame with a camera.

From Harvey to Max, Adam not only steadfastly employs clay animation but also persistently tackles its most challenging elements: fire, water, electricity, and virtual programs. In Harvie Krumpet, the young Harvie roasts ham over a fire in Polish snow; in Mary and Max, Mary burns Max’s letters in anger, confusion, and anxiety. Both scenes required “fire,” which Adam achieved using red cellophane or installing light bulbs beneath the fire. In other clay animations, fictional programs are often created using Flash compositing. However, in these two films, whether it’s the Busby Berkeley film Harvey watches on TV or the lottery draw Max views on television, the creators achieved the effect by placing paper cutouts depicting the programs behind the TV screens and filming them frame by frame as the content changed. It’s worth noting that while “Harvie Krumpet” omits smoke effects for Harvey’s cigarette, Adam explicitly depicts smoke in “Mary and Max.”

Choosing clay animation means embracing countless challenges and effects that are notoriously difficult to achieve. Yet for Adam, it’s precisely these obstacles and the experimentation required to overcome them that make clay animation feel authentically real.

II. The Evolution and Continuity in Puppet Design

Adam’s puppets are larger than those typically used in clay animation, averaging 30 centimeters in height—a dimension consistent from Harvey to Marx. This larger scale stems from Adam’s congenital condition, which causes more pronounced body tremors during movement. Larger puppets facilitate easier manipulation.

In terms of character aesthetics, both films share numerous similarities. First, the puppets feature a predominantly light gray skin tone—a trait consistent since Adam’s debut work, “Uncle.” Second, nearly all puppets possess two large eyeballs, a signature element of Adam’s animated style. The reason for saying “almost all” is that in “Mary and Max,” Adam experimented with black bean eyes for the characters of Mary and her mother. Black bean eyes are more common in other puppet animations, such as China’s ‘Afanti’ and South Korea’s “Doggy Poo.” They can express actions like blinking and various expressions through changes in the shape of the eyes. Adam’s “large eyeballs” represent a distinct approach to puppet animation eye design. Expressions are conveyed not through direct eye deformation but by shifting pupil positions, with blinking requiring coordinated eyelid movement. The British “Wallace & Gromit” series also employs this “large eyeball” eye design. Additionally, Adam’s puppets feature relatively large noses. Male characters have notably prominent ears that often stand out horizontally from the sides of the head, while female characters possess smaller ears typically concealed by hair or headscarves. Finally, adult puppets created by Adam maintain a head-to-body ratio of approximately 1:2, whereas children and elderly puppets adhere to ratios of 1:1.5 or 1:1.

The above outlines consistent elements of Adam’s puppets from Harvey to Marx, while the most significant change lies in materials—directly impacting the execution of expressions and movements. In “Harvie Krumpet,” puppets used an extremely rigid resin material, rendering their legs immobile. In fact, no character in Harvey walks with visible leg movement. When depicting motion—such as Harvey’s mother chasing him through the house from 3:30 to 3:35—their legs are cropped out of the frame, showing only the moving upper bodies. In “Mary and Max,” the puppets are made from a relatively soft clay material. Consequently, you frequently see Max dragging his heavy body through the dark streets of New York, or young Mary walking hopefully to the mailbox to post her letter. The change in material significantly impacts not only the characters’ movements but also their facial expressions. In “Harvie Krumpet,” the characters’ mouth shapes were pre-made and applied to designated areas on their faces, resulting in only two or three variations. In “Mary and Max,” however, you can observe a rich array of facial expressions, particularly a greater variety of mouth shapes. Furthermore, in the Harvey segment, many shots are static frames where characters only blink; in the Max segment, such static frames have become extremely rare. The expanded possibilities afforded by material variation represent an area where Max surpasses Harvey.

III. The Changing and Unchanging Themes of the Films

In terms of subject matter, “Harvie Krumpet” and “Mary and Max” share a common thread: both portray individuals with congenital physical or psychological conditions. This may be linked to the director’s own physical ailments mentioned earlier. Through his personal experiences, he possesses a unique understanding of the social psychology of marginalized groups.

Humanity stands as the shared thematic core of both films. Indeed, even the titles reveal Adam’s profound focus on human nature. “Harvie Krumpet” and “Mary and Max” are both named directly after their protagonists—a practice increasingly rare in contemporary Hollywood animated blockbusters. Many contemporary animations focus excessively on depicting bizarre environments, story settings, and characters, while rarely delving deeply into human nature. Adam’s films, however, spare no effort in exploring this theme.

Some might label Adam a fatalist, arguing that congenital physical or psychological conditions are nothing but cruel twists of fate. In truth, from Harvey to Max, Adam seeks to express neither pure fatalism nor the belief that humans can conquer destiny, but rather a complex perspective between the two: When Mary earns her doctorate, publishes a book, and confidently heads to New York to find Max, she finds she cannot control her own happiness. Max sends her a letter severing their friendship, and her husband has fallen for another woman—here, we see life is not entirely within our grasp. Then, when Harvey was happily spending his twilight years with his wife, she suddenly died of a cerebral hemorrhage. Fate seemed to be playing cruel jokes on him. Yet in the end, Harvey emerged from suicidal thoughts and continued to enjoy his remaining days at that station where no train would ever arrive—here, life is shown not to be entirely subject to fate’s dictates either.

Life is a complex process governed by both human agency and fate—this is what Adam sought to convey. Of course, in “Mary and Max,” he also explores the psychological need of marginalized groups: what they require is not pity or charity, but equal friendship.

IV. The Constancy and Variation in Plot Structure

The primary consistency in plot structure between the two films lies in their biographical narrative approach. “Harvie Krumpet” chronicles the life of Harvie, while “Mary and Max” recounts the story of its two protagonists over a span of approximately twenty years. Both films adhere faithfully to a linear progression of time, place, and events—free of flashbacks or digressions—presenting their narratives in a straightforward and objective manner. Unlike conventional narrative techniques, biographical storytelling allows characters’ psychological and behavioral shifts to unfold over extended periods as they grapple with diverse events. While narrative structures might depict a single shift in a character’s perspective—or none at all—biographical approaches often reveal multiple profound transformations in their outlook.

Though both films employ biographical narratives, their plot progression differs. The Harvey film relies entirely on voice-over narration to advance the story, with the protagonist having no spoken lines. The Marx film refines this approach: while still using voice-over as the main thread, it incorporates numerous self-narratives from the protagonist’s letters. This technique allows the voice to shape the character’s image, making them more vivid and dynamic, and facilitates a deeper exploration of human nature.

Another consistent element in the narrative structure from Harvey to Marx is that both protagonists contemplate suicide but ultimately refrain from taking their own lives. Suicide, as a means of escaping life’s hardships, is typically chosen when individuals are driven to the brink. Both Harvey and Mary contemplated suicide—the former through medication, the latter by hanging—indicating they were both pushed to a desperate impasse. As the plot unfolds step by step to these despairing situations, it reaches its climax. Coincidentally, both films feature an interlude at these breaking points, accompanied by surreal scenes involving the protagonists—the former with a wheelchair dance, the latter with Mary conducting at the dinner table. Musically, the piece chosen for “Mary and Max” more effectively captures the characters’ despair, profoundly stirring the audience’s emotions. This scene is widely regarded as the film’s most iconic moment. Following these tense suicide-themed sequences, Adam’s narratives invariably take a turn for the better, allowing protagonists to rediscover their will to live—Harvie realizing he still wants to survive, while Mary receives another letter from Max. From this point, the stories approach their conclusions as conflicts are resolved.

It must be said that the most crucial element in Adam’s films is forcing protagonists into such desperate situations. All preceding narrative groundwork serves to maximize the impact of this climactic moment. Here, “Harvie Krumpet” and “Mary and Max” diverge in approach: the former builds tension through cumulative negative events, while the latter employs a double-blow structure.

In “Harvie Krumpet,” events almost always come in pairs—one positive, one negative; or one neutral, one negative. His robust growth was a positive, yet his discovery of a congenital disease was negative; documenting his mother’s various “facts” was neutral, but being bullied by schoolmates was negative; enjoying work with his father was positive, but his parents’ tragic freezing deaths were negative… Overall, Harvey’s life contained fewer good events and more bad ones. Moreover, the bad events are always conveyed in a very straightforward and objective manner, like in a biographical narrative—such as his removal of a testicle, being declared infertile, his wife’s sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage, and so on. These misfortunes not only accumulate in Harvey’s mind but also settle in the audience’s hearts. As this accumulation grows heavier, it eventually reaches a breaking point, giving birth to Harvey’s desperate predicament.

In “Mary and Max,” Mary’s despair stems from a sudden double blow: being abandoned by both her pen pal and her husband. For over seventy minutes, the film paints a portrait of how precious the friendship between Mary and Max has become, and how desperately each needs the other. It even portrays Mary as a bride, living the enviable life of happiness everyone dreams of. Yet at this very moment, Adam brutally shatters both perfectly intact mirrors: her pen pal sends a letter severing ties, feeling betrayed, while her husband meets a new girlfriend during his travels. Had it been just one blow, Mary might have found solace in the other anchor. But with both pillars of her life torn away, she has nowhere left to turn—plunging her into utter despair.

Adam’s narrative structure revolves entirely around this abyss. What the protagonist chooses after emerging from this abyss is what matters most to them—and what the film celebrates most profoundly. In “Harvie Krumpet,” after his abyss, Harvie chooses to go naked to the station, choosing to savor the remainder of his life. For him, life itself is paramount, and living courageously is the film’s greatest tribute. In “Mary and Max,” Mary chooses to give birth to and raise her child, and to travel to New York to meet her pen pal Max. For her, the friendship between her and Max—a bond transcending romance—is the most important thing, and this friendship is what the film celebrates most.

V. The Evolution and Continuity of Cinematographic Techniques

In terms of cinematographic techniques, “Mary and Max” differs significantly from “Harvie Krumpet” in several aspects. Some variations stem from the need for distinct visual effects, while others represent refinements and innovations. Here, we illustrate each approach with a specific example.

First, regarding color palette selection: “Harvie Krumpet” employs full color throughout, showcasing a vibrant spectrum of hues that mirror the protagonist’s richly diverse life. In contrast, Max’s segments employ two distinct filters. For Mary’s rural Australian setting, a sepia filter is applied, rendering everything in warm brown and yellow tones. This likely reflects Adam’s own childhood memories of Australia. For Max’s urban New York backdrop, a gray filter is used, casting everything in black or deep gray. This may symbolize the persistent gloom and melancholy of Max’s state of mind. Notably, the small flower Mary sends Marx is the sole splash of red in this gray landscape, symbolizing the precious friendship between these pen pals. This technique, previously seen in “Schindler’s List,” marks its first use in an animated film.

Secondly, while differing color palettes serve distinct narrative purposes, the variation in musical elements more profoundly reflects “Mary and Max”‘s refinement and innovation over “Harvie Krumpet.” Beyond the shared device of interludes playing when protagonists face dire straits, Harvie’s segment features sparse background music, lending it a somewhat somber tone. In contrast, Max’s segment frequently employs atmospheric background music. Whether during lighthearted or heavy moments, and especially at the film’s conclusion when Mary arrives at Max’s home, sees the objects he described in his letters, and finally discovers the wall on the roof covered with her own letters, distinct musical selections enhance the atmosphere. It must be said that, from the perspective of musical usage, “Mary and Max” demonstrates greater maturity than “Harvie Krumpet.”

This article compares “Harvie Krumpet” and “Mary and Max” across five dimensions: film form, puppet design, thematic focus, narrative structure, and cinematographic techniques. In truth, numerous other elements warrant comparison—such as their depictions of pets and their symbolic bus stops—all embodying the duality of “change and constancy.” Due to space constraints, these cannot be elaborated upon here. Through these elements of “change and constancy,” we can appreciate director Adam Elliot’s unique and increasingly mature artistic appeal.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Mary and Max 2009 Animation Film Review: From “Harvie Krumpet” to “Mary and Max”: The Director’s Evolution and Continuity