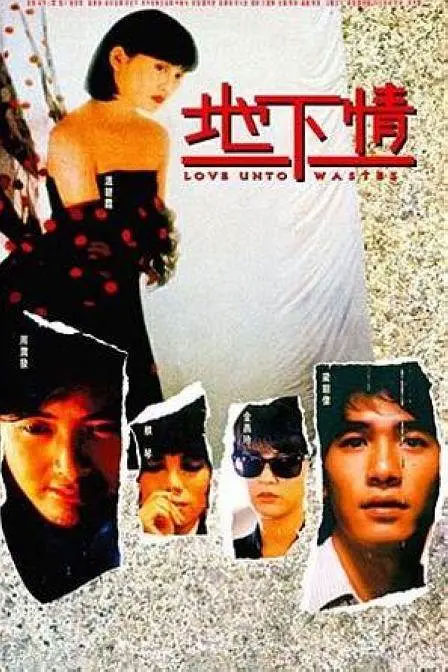

Film Name: 地下情 / Love Unto Waste

Qiu Gangjian and Guan Jinpeng collaborated on five films in total, with “Love Unto Waste” being their second. Though less celebrated than their later works like “Rouge,” “Center Stage,” or even “Full Moon in New York,” it remains the piece Qiu Gangjian himself holds in highest regard throughout his forty-five-year screenwriting career. “Love Unto Waste” features a love triangle, bloody murders, and police investigations, yet these elements dilute each other when piled together in the film. It is not a genre narrative. Rather than telling a complete story, it aims to present an urban portrait of alienation and a thriller about love and desire. Ruan Bei’er (played by Wen Bixia) and Zhang Shuhai (played by Tony Leung) meet by chance in a bar. Zhang Shuhai then abandons his girlfriend and falls in love with Ruan Bei’er. He then meets her two former roommates: the frustrated actress Liao Yuping (played by Kim Ying-ling) and the bar singer Zhao Shuling (played by Tsai Chin). The film unfolds at a leisurely pace in its first half, but Zhao Shuling’s unexpected death plunges the previously aimless love story into profound melancholy. Detective Lan Zhenqiang (played by Chow Yun-fat) then intervenes, probing the private lives of these three women and one man. It is also because of Shuling’s death that Zhang Shuhai unwittingly cheats on her with Liao Yuping. Amidst the awkward atmosphere, as the three lovers escort Shu-ling’s ashes back to Taiwan, the film “gradually transforms into a tale of two cities.” It concludes with the detective’s death on his sickbed, where he confesses to Shu-hai his obsession with the case: “I wanted to watch you waste your lives and emotions.” These words, spoken in that moment, are profoundly chilling.

Throughout the film, Shuling’s death serves as its most prominent dividing line. Before it, the narrative is saturated with a fragile romanticism, occasionally punctuated by sharp undercurrents. The best example is the scene at Yuping’s birthday gathering. Though the guests are strangers to each other, they still exchange playful banter, revealing a hint of intimacy. Shuling prepares a chicken and pig stomach soup for dinner, and Qiu Gangjian deliberately asks her to describe the steps in detail: washing the pig stomach four times, scraping it with a knife, stuffing the whole chicken into the stomach, piercing it with a needle, and then sewing it back up. Kwok Kam-pong also employed an exceptionally patient camera to observe the ingredients in her hands: the deformed pig stomach and the dead chicken with its drooping neck, causing Yuping to exclaim “Horrifying!” after a glance. Yet what truly made the horror palpable was Ruan Beier’s half-smile as she looked at Shuling and asked, “Have you ever had an abortion?” The smile instantly vanishes from Shuling’s face. Only then do viewers realize why Qiu Gangjian had so meticulously detailed the pig stomach chicken preparation earlier—the scraping motion of the pig stomach mirrors the surgical procedure of scraping the uterine wall during an abortion. Yet for whom did Shuling have the abortion? And why? The script leaves these questions hanging. Shuling’s abortion becomes a MacGuffin, abandoned without further pursuit.

However, beyond the abortion, Shuling introduced a second MacGuffin to the film: her murder. Although the film uses large bloodstains and a long take of Yuping’s terrified screams to present the scene of Shuling’s murder, and after her death, the emotional cliff the film had built up abruptly collapses, everyone’s mood plummets as if falling off a cliff. But after this brief shock, the audience quickly forgets the female corpse lying in a pool of blood. During interrogations, the detective appears more intent on probing the characters’ inner secrets than pursuing the killer. He even goes so far as to recount his own life story to them—a clear transgression, as he oversteps the narrative function confined to his role as a detective. Gradually, the audience also ceases to question why Shuling died or who the murderer is. Shuling began to exist only within the characters’ dialogue, becoming a name, an absent presence. It was precisely this dual, paradoxical quality that transformed Shuling into a kind of ghost haunting the cinematic text—a “ghost being an interstitial existence between presence and absence, possessing characteristics that cannot be grasped or touched in the real world yet persistently leave traces.” Yet beyond being a frequently invoked name, Shuling inhabits the narrative space in two additional ways.

First, Detective Lan Zhenqiang can be seen as Shuling’s stand-in, the embodied manifestation of the ghost’s “resurrection.” Lan Zhenqiang only appears after Shuling’s death. If Shuling’s death created a gap in the original character structure, then Lan Zhenqiang’s emergence fills this void, restoring the narrative to its original balanced state of “a love triangle plus an observer.” This interpretation rests on at least three points: First, in the scene where Lan Zhenqiang joins the trio for their first outing and they end up hungover on the street, Qiu Gangjian deliberately has Yu Ping declare, “Tonight, Shuling is coming back to haunt us!”—a seemingly intentional hint. Second, this surrogate dynamic is also glimpsed in the scene where Zhang Shuhai and Yu Ping return to the murder scene: upon seeing the unwashed bloodstains in the room, Yu Ping begins to cry. To comfort her, Zhang Shuhai has sex with her in the kitchen next to the corpse. Here, lust and death achieve a bizarre juxtaposition. The walls around them bear Shuling’s congealed bloodstains, while her belongings—clothes, photographs, bedsheets—litter the room. These traces starkly proclaim Shuling’s absent presence. The camera now seems to become the eyes of Shuling’s ghost, while we merely witness this act of infidelity on her behalf. Suddenly, Zhang Shuhai halts his movements and stares fixedly ahead (toward the camera). The lingering pause invites viewers to speculate: What did he see? Ruan Beier? The outline of Shuling’s corpse? Or perhaps some other unnoticed trace left by Shuling? Yet the shot cuts to reveal Lan Zhenqiang. Lan Zhenqiang, Shuling, and the camera’s voyeuristic gaze—these three elements bizarrely converge into a trinity at this moment. Thirdly, Lan Zhenqiang functionally continues Shuling’s narrative role: as an outsider to the “love triangle,” he observes and comments on the other three, occasionally lamenting his own emotional life. Simultaneously, Shuling and Lan Zhenqiang share a common trait: an unwavering faith in love. This very “faith” is precisely what the lovers in the triangle lack, explaining why their relationships feel as hollow and adrift as duckweed, even becoming tiresome. In Lan Zhenqiang’s final words to Zhang Shuhai, the differences and mutual disapproval between them are starkly revealed: I want to see how you waste your lives and emotions.” Shuling journeyed alone to Hong Kong, recording tapes for her lover whenever longing struck—a gesture undeniably profound. Had she not met an untimely death, had she witnessed this love triangle where no one emerged victorious, she might have spoken these very words. After all, this was not the love myth she had believed in. Thus, we might well regard Lan Zhenqiang as a stand-in summoned by Shuling (his very presence in the narrative stemming from her death)—a new voyeur and commentator, an intruder borrowed by a ghost to “reincarnate.”

Additionally, beyond this character structure that borders on “resurrection,” Shuling’s ghost haunts the visual narrative in a silent form. The most striking instance occurs in the penultimate scene: after the abortion, Yuping and Zhang Shuhai converse in a restaurant when blood (a complication from the procedure) suddenly trickles down Yuping’s calf. This blood evokes the earlier murder scene—the very bloodstained room where Yuping conceived. The bloodstain once again intertwines desire and death (Shuling’s and the infant’s). On one hand, this blood can be seen as the infant’s vengeance and lament, freshly strangled by the couple; on the other hand, it should be interpreted as the re-enactment of trauma: Shuling’s death, a hidden and deep-seated wound, lay dormant within Yuping’s consciousness. Now the scar has burst open, and the blood stirs not only shame and confusion within her heart, but also a stinging pain. “Ghosts point to the projection and pathology of repressed trauma.” Shuling’s ghost reappears once more, using the blood flowing now to caress and gently question Yuping: Why have you repeated my fate?

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Love Unto Waste 1986 Film Review: McGuffin and the Horror of Desire