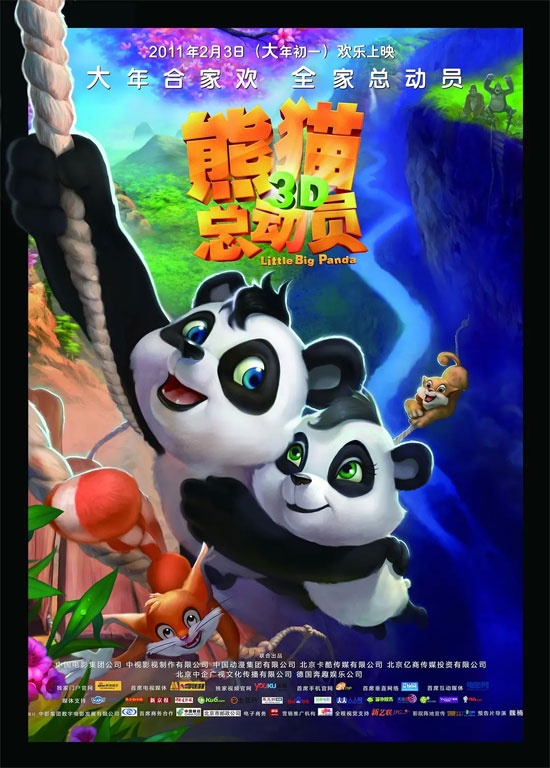

Film Name: 熊猫总动员 / Little Big Panda

Before its release, “Little Big Panda” touted promotional points like “China’s panda film challenging Kung Fu Panda,” 3D technology, a Sino-European co-production, a Hollywood director at the helm, and an all-star voice cast. Looking back now, only the all-star voice cast proved somewhat noteworthy—needless to say, renowned voice actors like Li Yang, Liu Chunyan, He Jiong, and other animation veterans, not to mention actors like Shi Banyu who gained fame voicing Stephen Chow films. Even celebrities like Zhao Zhongxiang, Han Qiaosheng, Huang Jianxiang, and Li Jing—who’d never voiced animation before—were recruited. Clearly, the producers put some thought into it.

However, this effort seems to have scratched only the surface. What truly determines a work’s core quality isn’t the voice acting, but the storyline. Thus, while the voice cast can serve as a catalyst to enhance box office appeal and remains a somewhat plausible marketing angle, expecting it to become the sole motivation for audiences to watch the film seems hardly feasible.

“Little Big Panda” suffers from a fundamental flaw in its plot. While superficially depicting an epic ‘Exodus’-style narrative, it fails to delve into the depth expected of the classic “hero-led exodus” template. This flaw manifests most glaringly in the protagonist Pandi’s growth arc, which involves virtually no personal sacrifice or struggle—instead unfolding as a divinely ordained, smooth-sailing journey. At critical junctures, the old immortal watching over Pandi from above would clap his hands, and a brilliant idea would instantly form in Pandi’s mind, effortlessly resolving his difficulties. Is such pampered protection truly the essence of heroism?

Mencius said: “When Heaven is about to confer a great responsibility on a man, it first afflicts his heart with sorrow, exhausts his body with labor, and exposes him to hunger and hardship. It disrupts his actions and frustrates his endeavors, all to temper his resolve and strengthen his capacity.” This passage not only reveals the essential path ancient sages took to greatness but should also serve as a guiding principle for all films depicting heroic growth.

Since we’ve mentioned the Exodus, let’s examine DreamWorks’ classic animated film The Prince of Egypt. As the representative of the Hebrews, Moses bore the mission to fight against the Egyptians, lead his people to escape, and establish a nation. Yet ironically, he was raised by the Egyptian royal family, which meant his growth inevitably required a choice to break away from wealth and familial bonds. If severing ties with power and wealth was relatively easier, then breaking away from his brother represented the greatest cost of Moses’s growth.

Many hero films feature the “father’s abdication” plotline, where the hero’s growth is accompanied by the father figure stepping down. The hero’s emergence as a hero is marked by the father’s withdrawal. Consider another DreamWorks animation, Kung Fu Panda, also featuring a panda protagonist. Po’s ascension comes at the cost of the passing of the legendary Master Turtle. Without the previous hero stepping aside, the new hero could never truly become independent. He would remain perpetually dependent, forever living under the shadow of his predecessor’s glory, unable to shine with his own brilliance.

Returning to Little Big Panda, we see Pandi born into his mother’s warm embrace—she lives until the very end. He has friends, even a girlfriend. He is clever and brave, always surrounded by bamboo to eat. He effortlessly uncovers the jungle’s secrets, and every hardship he faces is resolved by the presence of deities. There is no rupture from familial bonds, nor any abdication of paternal authority. His spirit remains untroubled, his body unburdened by toil, his flesh untouched by hunger, his being never depleted. His actions face no disruption, and without straining his heart or tempering his spirit, he achieves what others cannot. This is not the growth of a hero; it is unfairness.

The plot of “Little Big Panda” does not truly celebrate heroism, for it suggests heroes achieve greatness without effort. Instead, it feels like a tribute to the “privileged offspring”—a child ‘born’ to deities who then “guarantee” his status as the next hero. Panda’s sole qualification for heroism is his divine lineage, a predestined inheritance. Such thinking is deeply flawed. Consider Moses: he was born to ordinary Hebrew parents. His selection by God came later and resulted from his own efforts.

If you seek a film depicting all the hardships a hero must endure, as described by Mencius, I recommend the Japanese anime “Berserk.” Of course, whether it’s “Berserk,” “The Prince of Egypt,” or “Kung Fu Panda,” these are adult animations. It’s both appropriate and necessary for them to carry deeper meanings. But does this mean “Little Big Panda,” intended for young children, needn’t possess such depth? Certainly, animations for children should be simple, but the prerequisite is that the portrayal of heroes must be accurate—that a person’s growth is not smooth sailing, but involves setbacks. We do not encourage a path of uninterrupted success simply because of a privileged background or connections.

A few additional points:

First, the film features some ingenious character design choices. For instance, adding a tuft of hair on Panda’s head was a cute touch. Unfortunately, the director applied this tuft to all pandas, turning it from a unique trait of Panda into a generic racial feature. This dilutes what was originally a brilliant character design element.

Second, the character of Leopard Mom is exhausting to watch because the director fails to clearly define her role: Is she a source of inspiration, the ultimate antagonist, or a comedic foil? She should have been portrayed as a loving mother, but the film gives her overly harsh dialogue, making it impossible for audiences to warm to her. She also serves as the ultimate obstacle for Panda, yet her tenderness toward her cub prevents viewers from truly hating her. She frequently plays the role of a bumbling villain whose attacks invariably fail. Yet when you realize this clownish antagonist is both a woman and a mother, the humor evaporates. One might argue that complex humanity is a virtue. While true, complexity is a double-edged sword—we need contradictory yet harmonious characterization. When all other characters remain flat while hers alone is multidimensional, it feels jarringly out of place.

Third, regarding 3D. Many claim that 2D hand-drawn animation can’t achieve 3D effects—this is incorrect. 3D doesn’t refer to three dimensions, but to a sense of depth. Three dimensions are computer-generated, while 3D effects—the perception of depth—are achieved through visual principles, independent of production methods. I’ll delve into this topic in detail in the next installment of “Anime & Manga Encyclopedia.”

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Little Big Panda 2011 Animation Film Review: Heaven will bestow a great mission upon the panda.