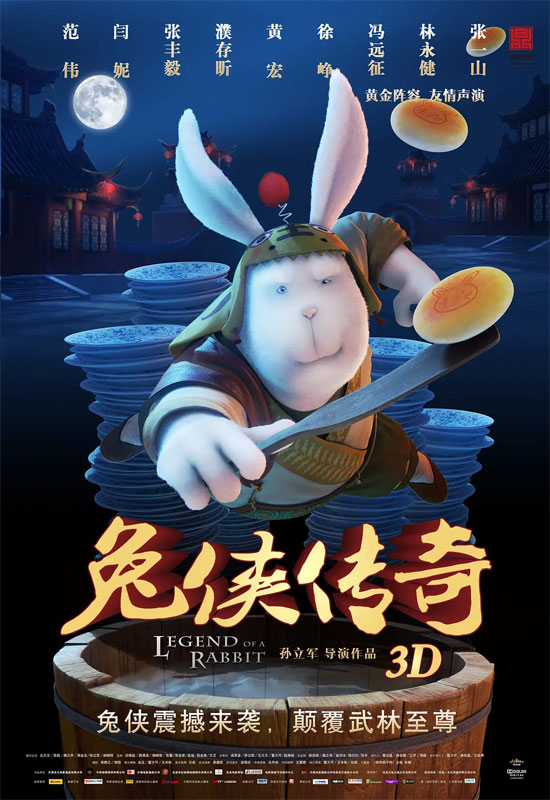

Film Name: 兔侠传奇 / Legend of A Rabbit / Legend of Kung Fu

When promoting domestic animations going forward, say whatever you want—just don’t mention how huge the investment supposedly is. Earlier, “Little Big Panda” claimed a 360 million yuan budget, and now “Legend of A Rabbit” boasts a 120 million yuan investment. Setting aside whether these figures are accurate, even if they are true, if the final box office only reaches a few million yuan, is this high investment something worth trumpeting? Or does it just make them look incredibly foolish?

I don’t know whether Zou Jingzhi merely lent his name to this film or actually wrote the story. I’d rather believe this story wasn’t penned by this renowned domestic screenwriter—otherwise, it would truly be a jaw-dropping embarrassment. Next, I’d like to address several particularly ridiculous issues concerning this film’s screenplay.

1. Why is the protagonist a rabbit?

Choosing a rabbit as the lead character must serve a purpose, much like DreamWorks selecting a panda for Kung Fu Panda to leverage Chinese cultural elements. If this year happens to be the Year of the Rabbit, making the rabbit the protagonist for marketing convenience might seem plausible. But what comes next? The film must be conceived and narrated around this rabbit.

Pandas are large and clumsy, and Kung Fu Panda masterfully portrays this, creating a striking contrast with the panda’s martial arts prowess. “Tusky” is a classic rabbit character, leveraging the rabbit’s white fur and long ears. Bugs Bunny is another iconic rabbit, embodying agility and swiftness. In the 1980s, we had an animated film called “The Rabbit with the Long Tail,” also featuring a rabbit protagonist, which played on the trait of rabbits having short tails.

What about “Legend of A Rabbit”? We find that beyond the incredibly superficial gimmick of the Year of the Rabbit, the film fails to explain why the protagonist must be a rabbit. We don’t know what specific characteristics of rabbits “Legend of A Rabbit” actually draws upon. In other words, come the Year of the Pig, could the same story simply swap in a pig protagonist and become “Legend of the Pig Hero”? And in the Year of the Dog, replace the hero with a dog and call it “Legend of the Dog Hero”?

If an animal-centric animated film fails to articulate the core reason for choosing this specific animal over others as its protagonist, and doesn’t fully leverage the animal’s physical traits, personality, and other defining characteristics, then it’s a failed concept.

2. What exactly is a “knight-errant”?

Though titled “Legend of a Rabbit,” the film offers no clear definition of this “knight-errant” concept. Admittedly, “knight-errant” has many interpretations—some even consider Lei Feng a knight-errant for embodying selfless altruism to the extreme. Such interpretations are valid, but only if grounded in an extraordinary rationale.

Japanese animation, while not explicitly defining “chivalry,” consistently explores why its gifted heroes fight. What purpose do their special abilities serve? Their answer boils down to two words: protection. Protecting loved ones, protecting those who deserve protection, protecting their world. This is interwoven with samurai virtues like loyalty, perseverance, and an unyielding drive to ascend, making Japanese “chivalry” profoundly multidimensional.

The concept of the “chivalrous hero” in American animation also has deep roots: Superman, Spider-Man, Batman, Green Lantern, The Flash, Iron Man—the list is endless. These heroes aren’t driven primarily by protection, but by a sense of duty—the idea that “with great power comes great responsibility.” The nature of this responsibility varies—from protecting individuals to safeguarding global peace. This symbiosis of power and duty constitutes the essence of the American hero.

By contrast, the ethos, ethics, and values embodied by the so-called “Rabbit Hero” named Rabbit Two remain profoundly ambiguous. It merely acquired martial arts skills that could make it a “hero” by chance. However, the film offers no depiction of how its spiritual world transcended the ordinary or how it reached a new realm. It feels like it was muddled into the situation, inexplicably defeated the boss, and then it ended. Without any cultivation of thought or progression, without any shift in perspective before and after, this doesn’t even come close to the character of a “hero.”

3. How Did Rabbit Two Defeat Bear Tianba?

Setting aside the final battle, Rabbit Two seemed to defeat the ultimate boss Bear Tianba without breaking a sweat, lacking any dramatic tension of a last-minute escape. But even focusing solely on how he managed to defeat Bear Tianba remains a puzzling mystery.

At the film’s outset, Xiong Tianba emerges as a master surpassing his own teacher, challenging him and forcing him to flee wounded. The master then transfers 80% of his martial prowess to Rabbit Two, a simple bun seller. At best, Rabbit Two might have grasped martial arts through cooking and menial tasks—yet he effortlessly defeats Xiong Tianba in the final showdown. Mathematically speaking, even if Rabbit Two inherited 80% of his master’s power and cultivated himself into a martial arts master equal to his master, he still shouldn’t have been able to defeat Xiong Tianba, who had forced his master into retreat. The film undoubtedly simplifies martial arts progression, strength comparisons, and combat in an unreasonable manner.

Setting aside the comparison of physical strength, what about the comparison of spirit? Rabbit Two also didn’t show any spiritual superiority over Xiong Tianba. If Tu Er’s goal was to deliver the token to Mudan and fulfill his master’s dying wish, the willpower driving him toward this objective was not necessarily stronger than Xiong Tianba’s drive to dominate the martial arts world. His goal held no inherent moral or spiritual superiority over Xiong Tianba’s ambitions. In other words, whether measured by righteousness or spirit, Tu Er failed to establish a decisive advantage over Xiong Tianba. How, then, could he ultimately prevail?

Or, taking a step back, even if Tu Er surpassed Xiong Tianba in strength, such a victory would remain unconvincing unless he occupied a spiritually superior realm.

4. Why did the master pass his power to Tu Er?

This is a particularly perplexing question: a martial arts master bequeathing his most vital techniques to someone he barely knew, having met only once. If we recall the plot in “The Heavenly Dragon’s Eightfold Path” where Xu Zhu obtained peerless martial prowess, we know the recipient of such transmission must have passed a decisive test—like the True Dragon Chessboard—and been verified as qualified. Even Po in “Kung Fu Panda” underwent a selection process, confirmed as the successor only after Master Shenlong’s personal observation.

No peerless master would ever impart their martial arts to someone they knew nothing about. Doing so would be irresponsible both to themselves and to the masses—what if this person turned out to be a thoroughly evil villain? The film’s handling here is a highly irresponsible simplification, advancing the plot for the sake of plot without considering the master’s possible true intentions. He was indeed aware his days were numbered and needed to find either an heir or a messenger. Yet precisely at this critical juncture, he should have exercised utmost caution and deliberation, never acting rashly.

This narrative lacks any comprehensive assessment of Rabbit Two’s aptitude and character by the master. Without such scrutiny, this entire plot point collapses.

5. Why is the monkey’s daughter a rabbit?

The fact that the monkey master’s daughter is a rabbit is just as bizarre a setup as Po the panda’s father being a goose. I don’t think “Legend of a Rabbit” should avoid learning from “Kung Fu Panda” entirely, but you can’t copy even its most iconic gimmicks. The racially confusing premise of “a panda’s father being a goose” has become uniquely symbolic precisely because of “Kung Fu Panda.” For “Legend of a Rabbit” to simply replicate this setup feels embarrassingly unoriginal.

Even if we concede it was intentionally planted as a sequel hook like “Kung Fu Panda,” when exactly would that sequel arrive? The next Year of the Rabbit? Because if this film doesn’t unfold during the Year of the Rabbit, the protagonist’s entire existence becomes nearly meaningless. Thus, from any perspective, the “monkey’s daughter is a rabbit” premise is a failed, unoriginal, and utterly stale concept.

6. Why did Xiong Tianba disguise himself as a panda?

Xiong Tianba could have disguised himself as a panda, but it needed justification. I simply couldn’t discern any necessity for him to adopt a panda appearance in “Legend of a Rabbit.” Was it truly to prevent audiences from missing the connection to “Kung Fu Panda”?

Moreover, as a major antagonist, adopting a panda’s appearance is utterly inappropriate. Pandas are China’s national treasure, historically associated with cuteness and endearing innocence—never with evil. Where did the Legend of a Rabbit crew get the idea to smear such a dark stain on this cherished image in the hearts of the Chinese people?

Beyond these six major issues, the film’s shortcomings in minor details are too numerous to list. Here are just a few examples:

For instance, while the fur rendering for Er Tu, Peony, and Xiong Tianba showed some creativity, not all animal characters could be depicted as either spiky or completely smooth. The little rabbit beside Er Tu and Peony looked utterly unnatural, like it was made of wax. And those cows? They were practically golden bulls.

Take the scene where Rabbit Two first meets Peony: the two robbers get far too much screen time. Their scenes have no connection to the main plot development. They should have merely introduced Peony and allowed her to showcase her martial arts skills—there was no need to spend so much time fleshing out these two characters. While these characters possess some humor, a film should minimize scenes that stray from the main plot and lack relevance to the core narrative. After all, it’s not meant to be a hodgepodge.

Additionally, if Rabbit Two’s skill and identity as a fried cake seller could be integrated into his martial arts abilities later on, it would create a stronger sense of unity. The sequence at the beginning where Rabbit Two drops the fried cakes all over the ground and then discovers his injured master while picking them up feels awkward in every aspect—from the character’s movements and expressions to the objective environment.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Legend of A Rabbit 2011 Animation Film Review: The Weird Stuff About Rabbit Number Two