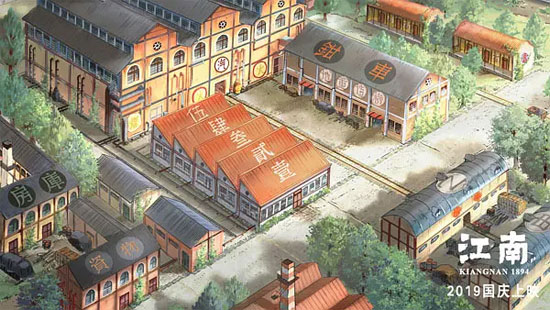

Film Name: 江南 / Kiangnan 1894

Set against the backdrop of the late Qing Dynasty, with the real-life Jiangnan Shipyard and Old Shanghai as its settings, and drawing inspiration from the nation’s military industry, “Kiangnan 1894” stands as an exceptionally rare realist animated film. To my knowledge, this subject matter represents a first for domestic animation. In this sense, the creative team deserves recognition for their boldness. For if we never dare to explore uncharted territories or challenge the unknown, we will forever remain like the Beiyang Fleet depicted in the film—borrowing foreign techniques without mastering them, unable to stand proudly among the world’s nations.

Yet we must also acknowledge that our animation teams still struggle to fully master such subjects. This struggle manifests in their difficulty portraying grand historical perspectives, depicting complex human nature, and focusing on truly powerful narratives—elements that form the core of any realistic work.

Set during one of China’s most humiliating historical periods, “Kiangnan 1894” fails to convey the profound national anguish and pressure of the era. Shanghai’s streets and markets appear serene, with life proceeding at a leisurely pace—as if foreign invasion had no impact on daily routines or mentalities. The signing of humiliating treaties fails to stir societal tension or outrage. This creates the impression that whether ships are built or machine guns acquired is of little consequence. While the naval battle in the latter half is intense, it feels too distant from daily life, lacking a palpable sense of crisis. Without the urgency of imminent danger and the imperative to save the nation, how can the patriotic devotion and self-sacrifice of a generation of Chinese craftsmen feel authentic?

Though A-Lang is the protagonist, his character lacks memorable depth. The initiation ceremony, meant to be the film’s emotional climax, fails to move the audience deeply. The root cause lies in shallow characterization and the simplistic, black-and-white treatment of complex realities. The good remain perpetually virtuous, the wicked eternally depraved. The protagonist’s growth lacks any truly agonizing dilemmas or crushing setbacks that could propel him to new heights. The limited screen time shared between A Lang and his master renders their parting far less poignant than it could have been.

Most crucially, the film fails to clarify its core narrative: is it about a master-apprentice bond preserving craftsmanship, or a prodigy saving the Jiangnan Shipyard and pioneering a new era of national defense? It seems to want to be everything, yet ultimately achieves little focus. Given the shipyard setting, the narrative should culminate in shipbuilding. Instead, the film devotes extensive screen time to machine gun construction. This disconnect renders both the opening dream sequence featuring an airship and the closing scene of a giant vessel launching into the sea feel detached from the main storyline.

Why insert such a romanticized, imaginative sequence—the dream airship—into an otherwise starkly realistic animated film? This choice may be linked to a strikingly similar Japanese film. Hayao Miyazaki’s animated film “The Wind Rises” shares striking parallels with “Kiangnan 1894.” Both chronicle the journey of a genius designer and depict the creation of pivotal war machines like the Zero fighter. “The Wind Rises” opens with a childhood dream sequence where the protagonist soars through the skies aboard an airship of his own invention.

The key difference lies in the core themes: “The Wind Rises” is fundamentally about designing fighter planes, so the aircraft in the dream resonates with the real-life aircraft that followed. In contrast, “Kiangnan 1894” features a dream about an airplane, yet the protagonist ultimately designs a ship—a rather incongruous outcome. The dream sequence in “The Wind Rises” culminates in war breaking out and the protagonist’s plane being shot down, triggering a profound sense of crisis about reality and revealing why designing the Zero fighter was so crucial for Japan. In contrast, the dream flight in “Kiangnan 1894” ends with the aircraft being knocked down by flyswatter-shaped clouds—a purely childish game with no connection to reality whatsoever. It can be said that the imagination in “The Wind Rises” serves to amplify the imagination of reality, while the imagination in “Kiangnan 1894” serves to diminish the imagination of reality. Thus, their expressive effects within films of the same realist genre naturally differ greatly.

The Wind Rises opens with the line, “The wind is rising. We must strive to survive,” and closes with, “Those who depart never return. Airplanes are cursed dreams, swallowed by the sky without a trace.” Both statements carry immense weight. The former explains why airplanes are built—though they bring brutal warfare, they are also born from the struggle to survive. The latter reflects the director’s contemplation of such war machines. “Kiangnan 1894” also depicts the design of war machines, culminating in defeat. Yet it fails to adequately explain why China sought to build ships, why it ventured to sea, what original aspirations it reflected, or what lessons China gained from its naval defeat. This creates a perceptible gap in logical connection between the naval defeat and the launch of the giant vessel after the founding of New China—a link that remains unexpressed and unexplained.

Thus, the realism in “Kiangnan 1894” presents a simplified version of reality—a transparent reality, if you will. Through this transparency, the historical perspective and human emotions that should be visible remain obscured. It is hoped that future realist works will dedicate more effort to making the attributes of reality more substantive.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Kiangnan 1894 2019 Film Review: Transparent Reality