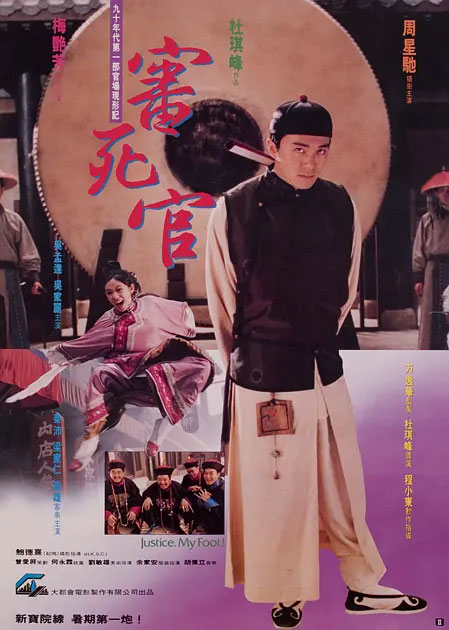

Film Name: 审死官 / Justice, My Foot! / 審死官

The style of “Justice, My Foot!” actually differs significantly from most of Stephen Chow’s absurd comedies. Compared to films like “Hail the Judge,” which share similarities in plot progression and character archetypes (such as the dog-walking young master Bin being the son of the naval commander, mirroring the villain Chang Wei in “Hail the Judge” who is also the naval commander’s son; or the final appearance of the Imperial Inspector, mirroring Stephen Chow’s final identity in “Hail the Judge”). Unlike “Hail the Judge,” which maintains its absurdity right up to the very last second, “Justice, My Foot!” concludes with less catharsis and features overtly satirical scenes throughout.

First, the characters in this film are unique. Stephen Chow’s character undergoes a transformation from suppression to triumph, a trope common to all films that need not be elaborated upon here. The supporting cast deserves attention. The first Guangdong magistrate is an elderly man—inept and easily swayed by rumors. Song Shijie effortlessly manipulates him, embodying the archetype of a bureaucrat who, after years of experience, becomes a timid peacemaker incapable of decisive judgment. His character is portrayed as a decrepit old man.

Next is the timid and cowardly Yang Xiuzhen (played by Wu Jiali). Her defining trait is crying at every turn—a classic example of “big breasts, no brains.” After her husband’s death, her first instinct is to flee to unreliable relatives, ultimately reaping what she sows. At the slightest setback, she cries out, “I won’t press charges!” In contrast, the bystander Anita Mui proves more resolute than her. This character embodies the typical commoner whose fate rests entirely in the hands of Song Shijie and his faction of officials—whichever side prevails determines her destiny.

Next is Yang Qing (played by Gao Xiong), whose role mirrors Yang Xiuzhen’s. Beyond his martial prowess, he comes across as a dim-witted giant with minimal screen time. His sole purpose is rescuing people at the execution ground and intercepting the official carriage to lodge a complaint. He is the most “pure-hearted” character in the entire play. He never questions anything others say. The former, Yang Xiuzhen’s second brother, was cheated out of 50 taels of silver. The latter, Song Shijie, is the protagonist, so he becomes the hero.

Next are the three key officials in this film: Ho Yu-ta (played by Wu Mengda), who “talks nonsense”; the Shanxi Provincial Governor (played by Leung Ka-yan), who “listens to his mother”; and the Eighth Provincial Inspector (played by Qin Pei), who is “ruthlessly upright.” Though they are clearly villains in this story, upon reflection, were they truly villains from the moment they appeared? As the newly appointed Magistrate of Guangzhou, He Ruda naturally knew Song Shijie was a tough nut to crack. That’s why he kept throwing obstacles in Song’s path—like beating up Anita Mui, to name just one example. First, within the film’s narrative, before He Ruda, Song Shijie had consistently relied on his silver tongue to win unjust cases—otherwise, he wouldn’t have lost over a dozen sons. The previous magistrate was timid, merely a puppet in Song’s hands. Here’s proof: When Anita Mui brought Yang Xiuzhen to court, Song went to see her but was blocked by officers. Song immediately declared, “I used to come and go freely here,” revealing his former arrogance. Thus, it’s natural for a new official to crack down on local power brokers. Unfortunately, he targeted the protagonist, making him the antagonist. He Ruda also has a memorable moment: when the Shanxi Provincial Administration Office tried to bribe him, he vehemently opposed it—only for his wife to accept it later. This anecdote was quite popular a few years ago. It essentially proves that Magistrate He’s words were nothing but hot air. He Ruda had maintained a decent reputation until learning of the Shanxi Provincial Administration’s involvement in the case. From then on, he became a corrupt official, cowed by his superiors. Though not his direct superior, the Shanxi official held a higher rank—and that was enough. He Ruda is precisely the type who thrives in the bureaucratic arena: fiery toward subordinates yet obsequious toward superiors. Ultimately, his words carry no more weight than hot air. The Shanxi Provincial Administration’s entrance was more positive. When he first learned of the case, he vowed to dismember his sister and brother-in-law to repay the debt of death, proving he had some sense of justice. Yet his change was remarkably simple—his mother’s crying, fussing, and threatening suicide swept him away. Thus, beyond symbolizing officials exploiting their positions for personal gain, the Shanxi Provincial Governor also mirrors certain common traits among ordinary people. For instance, in marriage arrangements, there are often those peculiar men who only listen to their own mothers, completely disregarding the bride’s wishes. Finally, there’s the highly controversial Imperial Inspector. His appearance involves references to a certain national leader, making this film quite contentious. But let’s focus on the drama. Qin Pei rarely played positive roles in his early films (like the Gambling God’s Hong Ye), so his appearance naturally made audiences assume he was the villain. In the play, Song Shijie’s assessment of him was spot-on: “a despicable man with integrity.” His rescue of Yang Qing and the eventual victory in the case were all thanks to him. Yet he carries a certain “despicable” quality—he took the case because of Song Shijie’s accusation of “officials protecting each other.” But throughout the trial, he masterfully embodies the conflicted state of wanting to uphold integrity while shielding his colleagues. Thus, his ‘despicable’ nature is one of “mouth says no, body says yes.” He strives to preserve all facets of his character: he desires a just resolution to the case while simultaneously shielding his colleagues from harm. This approach mirrors certain tactics still prevalent in today’s bureaucratic circles.

Another notable character is Song Shijie’s mentor, a quintessential pedantic old scholar. He holds himself in lofty esteem, valuing ancestral traditions above all else. Consequently, he remains indifferent to Song Shijie’s actions, prioritizing the old ways above everything else.

As my title suggests, this isn’t a pure comedy—it’s a deeply realistic film. While it features villains facing justice, the three corrupt officials remain untouched. Song Shijie has simultaneously offended the county magistrate, the provincial governor, and the CPPCC chairman. If they choose not to pursue him, that’s one thing. But if they do, he’ll have nowhere to hide. This is precisely the film’s realism and its positive message. As I mentioned earlier, these three officials weren’t corrupt from the start—in fact, their true natures weren’t inherently corrupt. Otherwise, Song Shijie wouldn’t have faced such difficulty winning this case. Thus, the conclusion unfolds: those deserving execution are beheaded, both sides find peace, and no further complications arise. Life is like this. While it’s satisfying to see corrupt officials like those in “Hail the Judge” meet their end, not all officials are purely corrupt like the ones in that film. The outcome won’t always be as neatly resolved as we might hope, with all problems eradicated and joy spreading far and wide. So “Hail the Judge” is pure comedy, while “Justice, My Foot!” is life.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Justice, My Foot! 1992 Film Review: This is not a pure comedy, but life itself.