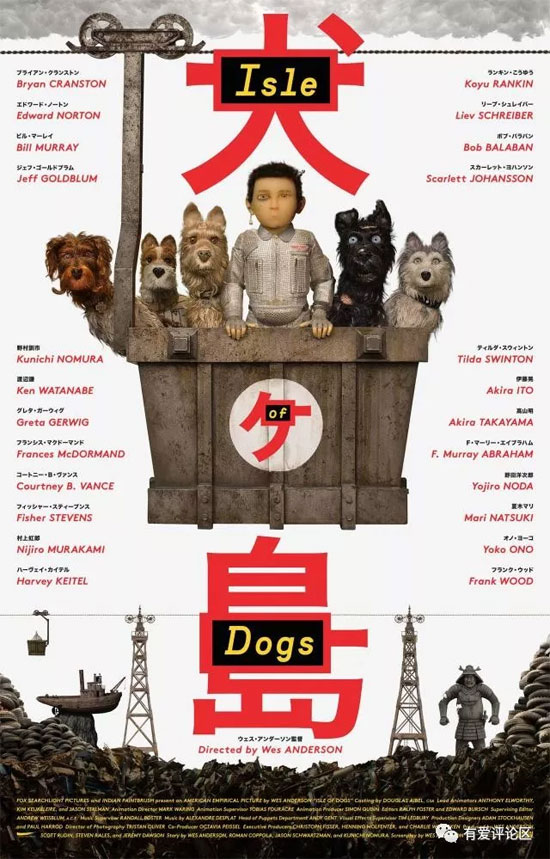

Film Name:犬之島 / Isle of Dogs

Why should we watch Isle of Dogs? The answer comes with several compelling reasons: it’s directed by the critically acclaimed Wes Anderson (marking his first film release in China), features an all-star voice cast (Tilda Swinton, Michael Norton, Stephen Moffat, Bill Nighy, Jeff Bridges, Tilda Swinton, Yoko Ono, Takayuki Yamada… This is what drew me in), its standout performance at the Berlin Film Festival, and the widespread acclaim from critics and audiences alike (setting aside certain white leftists’ tendency to over-interpret).

But these are all surface-level factors. After actually watching this film—with its uncomplicated narrative and ending that initially seems somewhat “universal”—what comes to mind when you reflect on it?

Each person arrives at a slightly different answer.

[Friendly reminder: Spoilers ahead.]

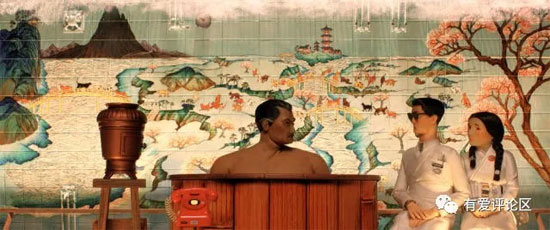

It must be said that the setting of Isle of Dogs is truly remarkable. The director, known for his obsession with detail and his compulsive attention to visuals, has set this story in a Japan that bridges past and present, brought to life through stop-motion animation. Connoisseurs will undoubtedly applaud the film’s technical achievements.

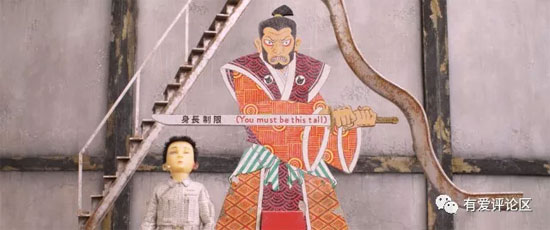

However, the film inevitably invites criticism for “overloading on exotic cultural elements” and “overly formulaic storytelling”—from the rousing taiko drums at the beginning and end, to the haiku that freeze history in time, the solemn shrines, the sumo matches featuring superstar wrestlers, the cherry blossoms symbolizing life and death, the rigidly formal politics, and even the freshly made sushi that made my mouth water… The film’s Japanese elements are too numerous, too dense, and too direct. Combined with lengthy stretches of deliberately untranslated Japanese dialogue, this approach may indeed leave some viewers feeling it “overdoes it.”

Yet, as the saying goes: Once you accept this premise, it’s surprisingly charming.

The dense “Oriental imagery” doesn’t overshadow the core narrative; instead, it effectively supports a story that remains fundamentally “Western” at its heart.

Returning to the opening question, viewers of Isle of Dogs will each find their own takeaway after the credits roll: Some see the dogs’ endearing innocence and boundless affection, their heartwarming bond with humans enough to bring tears to the eyes; others witness the fickleness and ruthlessness of politics, where shadowy machinations ensure no fundamental change; still others observe the deep-seated and stubborn servility, blindly feeding the powerful without a hint of self-awareness…

I’d only seen two Wes Anderson films before this—perhaps his most recognizable works: Fantastic Mr. Fox and The Grand Budapest Hotel. While my appreciation varies, two words define his style for me: absurd and amusing.

Isle of Dogs follows suit.

A defining feature of this film is its narrative perspective from the dogs’ viewpoint. This isn’t merely a superficial concept—it genuinely immerses the audience in the frustration and alienation of “incommunicability.”

The main “Five Dogs Squad” may each bear a grand title—Chief, Rex, Boss, Duke, King—but aside from Chief, who retains the heart of a stray, the other four remain domesticated creatures yearning for human affection.

The arrival of Atari, a young boy who travels to the island searching for his beloved dog Spot, intensifies and transforms the conflicts and perspectives within the canine crew. Moved by Atari’s actions, all four dogs subconsciously recognize this as the true, natural bond between humans and dogs. They then “coerce” the reluctant Chief into joining them on their mission to escort Spot back to the mainland.

On the surface, it seems like a predictable “underdog” narrative—a story of initial reluctance followed by redemption. Indeed, the film portrays precisely such a “heartwarming” tale: the leader stubbornly refuses to aid the outsider at first, only to find himself stranded alone with Atari. As they journey together, the man and dog grow closer, ultimately forging another timeless tale of friendship.

Yet I can’t shake the feeling that this is an absurd and stark story.

In my view, the leader was never truly “tamed.” His four years as a stray were merely part of the narrative. Retrieving sticks for Atari wasn’t obedience, but sympathy and boredom. More crucially, despite claiming to “hate fighting,” he had a history of unprovoked attacks— —If the first bite after being adopted, which injured a young boy, could be attributed to “fear,” then by the end, when Leader became Atari’s new guard dog with vastly elevated status, he could have easily “raised his standards”… Yet Leader still bit those who opposed the new mayor Atari. This wasn’t out of protective instinct, but rather, “I don’t even know why I did it (just like before).”

We can rationalize every action and experience of the Leader—caution, gratitude, emotion, desire—yet we cannot explain why it bites without provocation. Ultimately, we can only say it’s “untamable” or “just its nature”… This is the most absurd part of Isle of Dogs, yet precisely the most authentic.

This principle also applies to the “protagonist” Atari, whose actions simultaneously blend rationality and bewilderment—though one might dismiss his erratic behavior as “brain damage” from the metal rod piercing his head, that’s merely a red herring. Like the Leader, Atari too occasionally does inexplicable things.

The most iconic scene occurs when Atari passes by a playground. Despite the height difference and the Chief’s urging, he insists on sliding down the slide. In most instances of communication breakdown, Atari would gesture and talk to the dogs, but this time, he says nothing—he just climbs up and slides down…

Insisting on this stunt during a race against time seems easily explained—a simple “childlike spirit” could suffice. Yet delve deeper, and no one could truly articulate why. Atari just wanted to slide down that slide. There was no “why.”

The ending of Isle of Dogs isn’t exactly “heartwarming.” After all, the story’s canine ancestors fought a great war against humans. After all that, they still end up dependent on humans for survival (the setting hints at the original vision of “equality between humans and dogs”). Beyond the statue of Spot, there’s a cage with profound symbolic meaning… After the corrupt mayor’s downfall, Atari takes power and the dogs regain their good life—yet it hardly feels like a happy ending. When asked “What should be done to those who mistreat dogs?”, Atari’s immediate response is “death penalty,” only later amended to “detention and fines” after being reminded—but I believe “prioritizing dog lives over human lives” is what Atari truly desires…

This tale of ultimate “order” paradoxically radiates a wild, chaotic energy throughout.

Of course, this is quite subtle, and Wes Anderson doesn’t directly confront political metaphors or primal instincts in the film—that’s the director’s cunning.

This piece is a bit disjointed, partly because of Isle of Dogs’ “subdued” and obscure nature (forcing the blame). Sometimes, things don’t need to be spelled out… Right now, my mind is filled with the Joker’s iconic line from The Dark Knight: “I’m just a dog chasing cars. Even when I catch one, I don’t know what to do with it… I just need to do something.”

It feels particularly apt.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Isle of Dogs 犬之島 2018 Film Review: The absurd reality, the chaotic nature