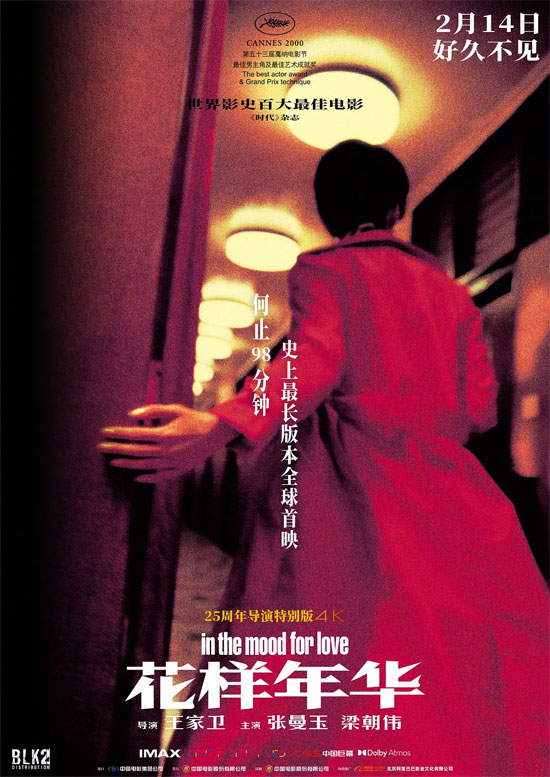

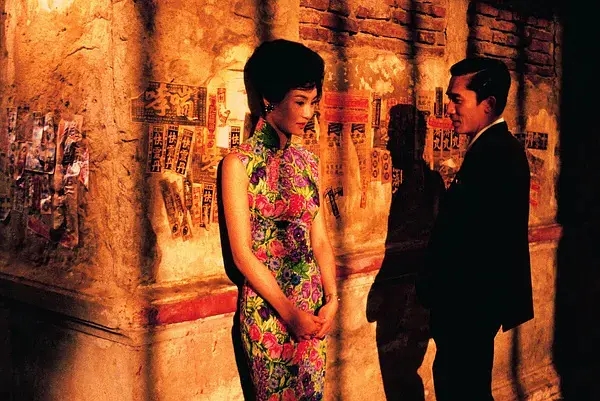

Film Name: 花样年华 / In the Mood for Love / 花樣年華

Two years ago, while reading Alain Badiou’s “Rhapsody for the Theatre,” I was startled by a passage:

“The male actor can forever stand on the edge of ambiguity, leaning against the boundary of his own universality.

The actress always stands at the boundary without boundaries, performing on the edge of nothingness.”

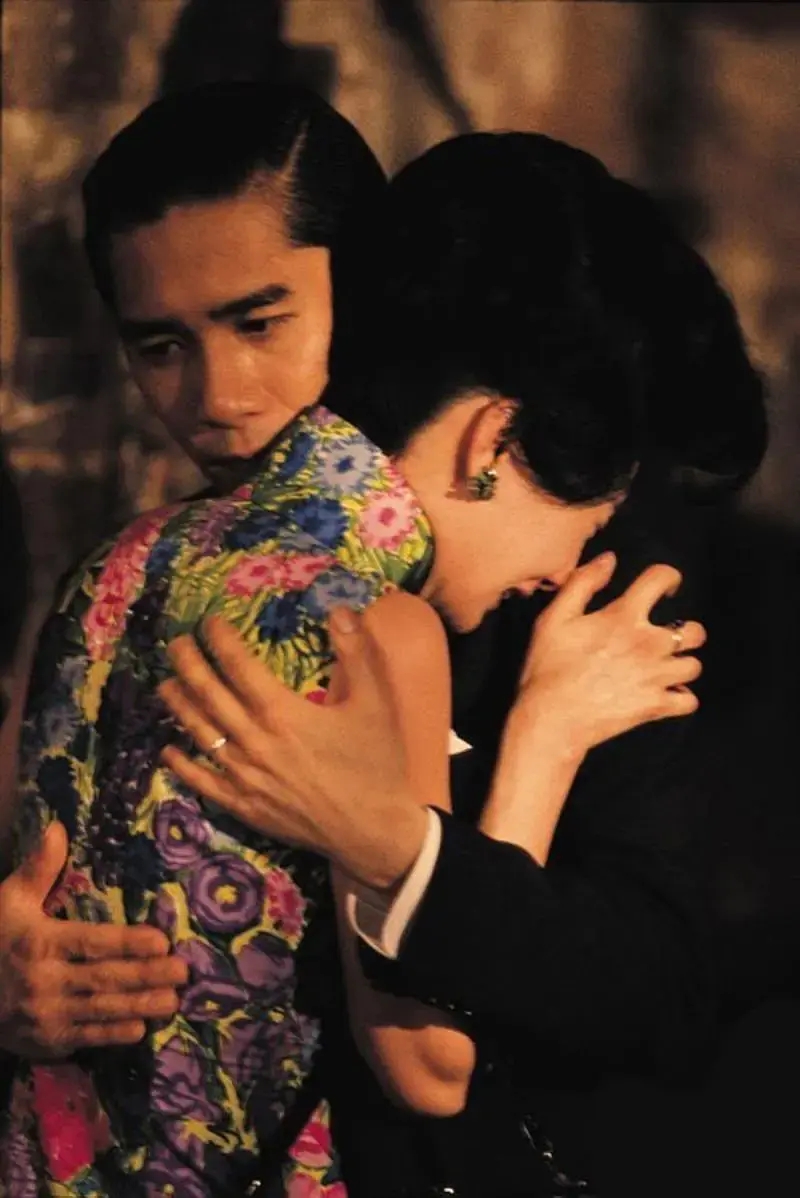

Alain Badiou didn’t name specific actors; he spoke of a universal truth. Yet in that moment of reading, only two actors came to mind: Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, and their shared performance in “In the Mood for Love.”

There’s no need to list the accolades this film has garnered. Simply revisit it during a mature phase of your life, and you’ll grasp its beauty and profound meaning.

It has nothing to do with whether you’re bourgeois, a Wong Kar-wai fan, or enamored with Tony Leung or Maggie Cheung as individuals. Nor does it matter how much off-screen scandal or box office success surrounds it… Its gaze remains fixed on two people trapped in a confined space. Their idle days, hesitations, pain, and fleeting joys all vanish like smoke and clouds—yet when you look back at this dense emotional tapestry, you may see yourself, and something universal. A sensitive director crafted the story; great actors portrayed the subtle, universal depths of humanity.

It was only upon revisiting “In the Mood for Love” years later that I was struck by its maturity and completeness. Like a powerful short story or a fully realized symphony, “In the Mood for Love” displays a fluid mastery and impeccable timing surpassing any of Wong Kar-wai’s other works.

Heaven, earth, and humanity aligned. In that era, the fully matured Wong Kar-wai met the equally matured Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, alongside the craftspeople who made this film possible: Christopher Doyle, Lee Ping-bin, and Du Du-zhi… They all had the patience to come together at the perfect moment to bring this story to life. Thus, a match made in heaven emerged—one that had never existed before and will likely never be replicated.

Compared to every film currently in theaters on February 14, 2025, “In the Mood for Love” stands atop another peak. This story carries no grand sentiment—be it about family or nation—making it utterly at odds with today’s popular narrative frameworks.

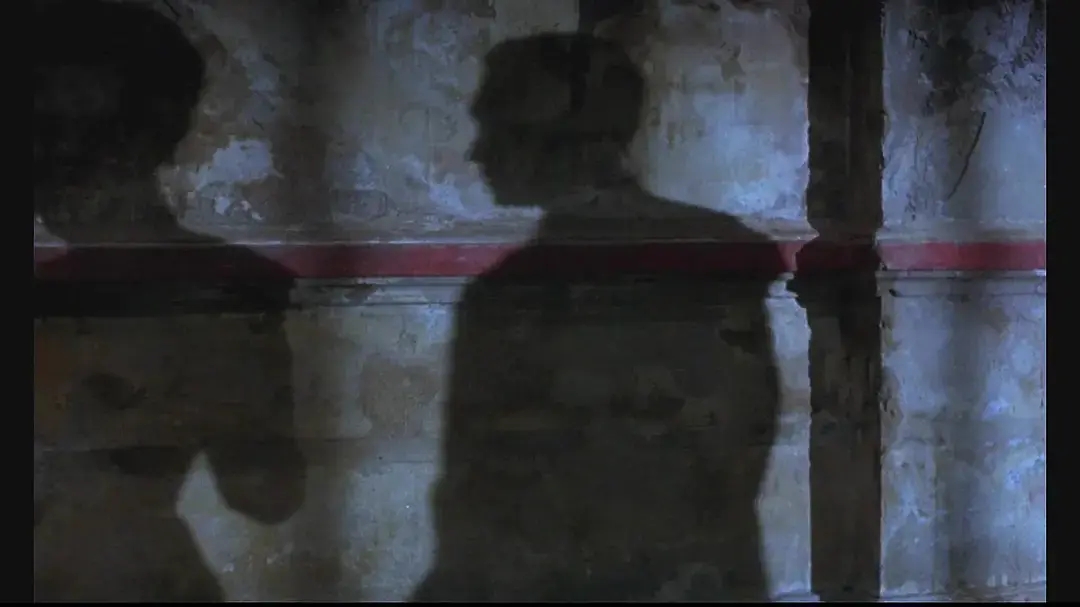

The focus remains squarely on cramped rental flats, deserted streets, suffocating workplaces, newsrooms, and dimly lit hotels. We see few others around them, yet we sense each person exists under others’ gaze—struggling fiercely to preserve their existence and a shred of dignity.

The encounter between Chow Mo-wan and Su Li-zhen occurs when they both decide to rent the same room. It is an ordinary meeting—like the exchanged glances on a train or in a café in any romantic film—except that Chow Mo-wan and Su Li-zhen represent the common Chinese people. Love takes a backseat to the necessities of life. We can remember the day we moved into a new place or started a job, but we cannot calculate the day when a passionate love affair began.

“Love knows no reason” became the central theme after their meeting. On one hand, they play the roles of each other’s partners, exploring when their illicit affair began amidst layers of taboo. Yet on the other, within this “play within a play,” they also test their boundaries: when did I fall for you? When did you develop feelings for me? Can we jointly define these limits? Zhou Mowen and Su Lizhen engage in another layer of contest.

In the duel between two people, Chow Mo-wan remained a steadfast hunter. At first, he might have been willing to play along with Su Lizhen, pretending to be her husband and feigning concern over when his lover might stray. But soon, his role became a form of pursuit—he sought to probe Su Lizhen’s emotions, guiding her step by step toward him.

Tony Leung has portrayed such roles multiple times throughout his career, and in “In the Mood for Love,” Chow Mo-wan embodies the perfect blend of seasoned sophistication and innocence. You can forgive his ambiguity, forgive his cunning, because you believe that from the very first moment he laid eyes on Su Lizhen, a profound transformation occurred within him—unrelated to “Mrs. Chow” or “Mr. Chen.” Chow Mo-wan exists along his own distinct, pure timeline.

Compared to Chow Mo-wan’s proactive, aggressive, defensive, and probing approach, Su Li-zhen seems to have passively fallen into a “trap.” But is she truly captured prey? Not entirely. Su Li-zhen may have felt an inexplicable attraction toward Chow Mo-wan upon meeting him, yet she was obscured by multiple identities: first Mrs. Chan, then Secretary Su, and only lastly herself.

Returning to the passage I mentioned earlier: the male actor stands on the edge of ambiguity, while the female actor stands at the boundary of boundlessness—in the emotional tug-of-war between the two, Chow Mo-wan displays a clear extra measure of resolve, while Su Lizhen remains perpetually disturbed by various gazes and definitions.

Take a simple example: from the outset, Su Lizhen embodies the role of the clear-sighted bystander. As Secretary Su, she knows precisely how to help her boss navigate his wife and mistress. She expertly makes calls, selects gifts, crafts meticulous schedules, and when his tie is askew, subtly remarks, “It’s noticeable if you look closely.” This reveals Su Lizhen as a seasoned veteran, adept at navigating social dynamics—a survival skill long ingrained in her. Yet why does she gradually become flustered and indecisive in her own emotions? Because her primary identity isn’t herself, but the “boundary” of others.

First, she was Mr. Chen’s wife, renting this apartment; then she was Su, the boss’s secretary, handling his affairs (including domestic matters); later, she became Yongsheng’s mother. When she reappeared in the rental apartment with the child, in others’ eyes, she was that child’s mother.

Su Lizhen only briefly “was” herself when she was with Chow Mo-wan. She loved reading martial arts novels and even wrote them quite well. She needed space to be alone. Even when neighbors invited her to eat with them every night, she would grab her thermos and head out to get a late-night snack.

To others, Su Lizhen was a stubborn, solitary wife. Her graceful figure and habits clashed with her surroundings, yet this was the only way she could carve out a sliver of breathing room within the cramped confines of her life.

The only moment we witness Su Lizhen truly relax is when she crosses her legs and reads a thick newspaper. Immersed in her own world, she can let go of everything for a moment, simply drifting along with the characters in the stories. No wonder Zhou Muyun quickly found a way to draw her in—why don’t we become “players in a play”? We’ll write our own story.

The “play within a play” in “In the Mood for Love” can be seen later in Ang Lee’s “Lust, Caution” through Wang Jiazhi’s obsession with the stage. A lonely wanderer finds herself under the gaze of attention in a specific moment—even if that gaze belongs to just one person—and she gains a moving radiance. For this, she throws caution to the wind.

Though Su Lizhen lacks Wang Jiazhi’s courage, she too grows bolder within the play-within-a-play. At first, she disguises herself as the boldly dressed Mrs. Zhou, batting her eyelashes and flicking her fingers to test the possibility of another kind of connection. Then, she adopts Mrs. Zhou’s taste, dipping her steak in mustard sauce and eating it despite the heat. Gradually, she—who never cooked—began preparing sesame paste, ostensibly for everyone yet truly for one person alone. Later, realizing she couldn’t escape this “play within a play,” she wept bitterly and made an even more forbidden decision…

All this existed within the framework of the “play within a play.” “When falsehood becomes truth, truth itself turns false.” Su Lizhen gave herself a justification. Within the fabricated world she and Chow Mo-wan built together, she laid bare her emotions, surrendering her heart to glances and physical touch. When doubt arose, she could retreat into the performance, tightly encasing herself within it. As long as the play continued, she remained within the safety of her self-defined boundaries. She felt the warmth of loving and being loved—and, of course, the mutual affection of friendship.

But for Chow Mo-wan, the “play within a play” was always temporary. He always needed a clear answer. I don’t care whether you’re Mrs. Chan or Secretary Su, whether I’m playing Mr. Chan or someone else. All I care about is where our feelings stand: I’ve posed the question, and I demand an answer.

The film’s most unsettling performance occurs while Chow Mo-wan waits in Room 2046. The moment he hears Su Lizhen’s hurried footsteps, his solemn expression instantly shifts to triumph—he has received an answer.

Yet Su Lizhen is not one to press the confirmation button with Zhou Mowen’s precision. She comes, but she departs swiftly; she affirms her affection, but she refuses to make the final decision. She could never escape her social identity to freely embrace the flow of emotion. Under the weight of countless gazes, she chose silence, departure, and oblivion.

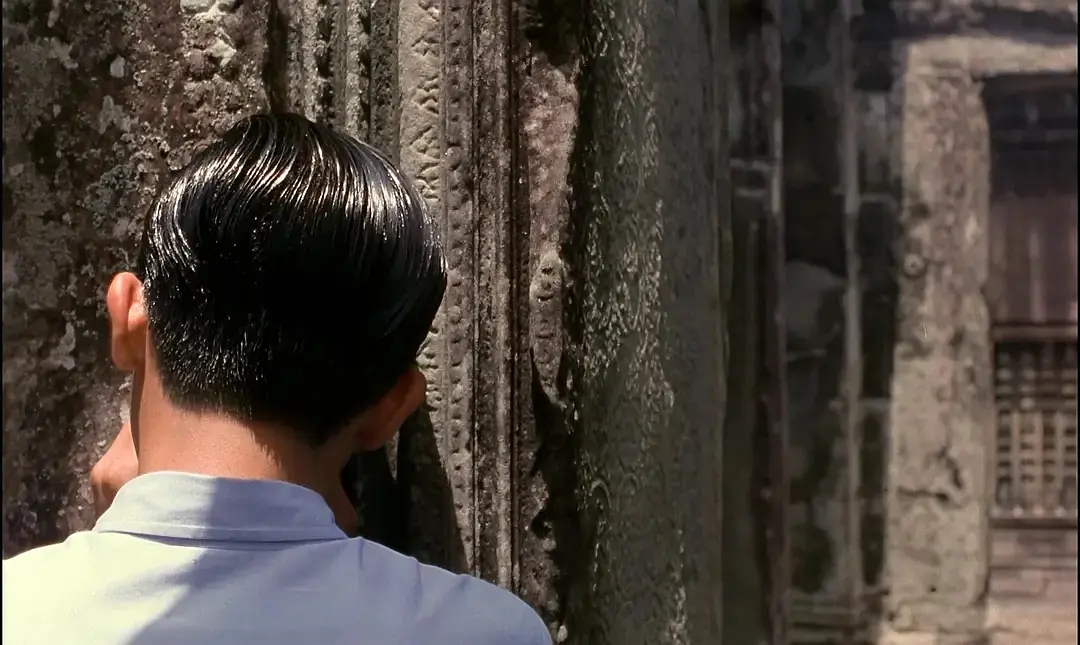

This was the part Chow Mo-wan couldn’t calculate, and it ultimately defined their love. Love doesn’t become eternal because it’s certain; it gains its enduring quality precisely because it leaves behind so much regret, uncertainty, struggle, and frustration. When you see Tony Leung’s Chow Mo-wan pouring his heart out to the cave at Angkor Wat, his silhouette resembles a lover in the throes of a passionate kiss. What he yearns for is that period—the turbulent highs and lows he experienced within it—which ultimately ended as their lives grew apart. And it could never be recreated.

It’s hard to say what significance such an exquisitely subtle emotional struggle—from its inception to its conclusion—holds compared to the certainty people seek today. Nowadays, people scarcely believe in love anymore, nor in chance encounters or promises. They trust only fleeting, definitive things, for they demand little time and leave few regrets.

When we revisit such a film in 2025, setting aside its artistic peak, we glimpse an era now vanished. There, in the year 2000 (not 1966), we see people still willing to explore how deep affection unfolds and leaves its mark on time, striving to understand it.

Sue’s beauty, courage, conservatism, and resolve represent not just her alone, but countless women trapped in cramped spaces. Chow’s doubt, anger, defiance, and flight mirror not just him, but millions of men who, in the dead of night, cannot escape their circumstances—driven toward deeper vengeance and final showdowns.

Under the ever-present gaze of others, words become veiled and circuitous, forever failing to reach their precise destination; under the ever-present gaze of others, the night streets become a stage where forbidden dramas must be performed, despite the deep-seated denial and suspicion lurking within; Under the ever-present gaze of others, food and clothing become language. Words left unsaid, deeds left undone—let them be replaced by these instead. Material things, intricate material things: seasonal vegetables, ties and leather bags, suits and cheongsams… all become people’s secret codes. They dance alongside their owners, circling in the nightlight, under the gaze of others.

Returning to “In the Mood for Love,” the intricate play of light and shadow, the drifting gazes, and the subtle inclinations of bodies on screen—I am certain I witnessed the greatest performance of our era. The unknowable affairs of the Eastern world are portrayed and narrated with such precision, condensed into two individuals, two symbols of beauty, who sail through another time and space in place of our ordinary, mundane selves.

Perhaps years ago we couldn’t grasp why the crumbling ruins of Angkor Wat should be linked to a secret—but after navigating our own turbulent passage through time and space, we understand: uncertainty, or the impermanence of life, is the only certainty. And “In the Mood for Love” gives us a precise coordinate: measure it, savor it, then choose to seal it away and forget.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » In the Mood for Love 2000 Film Review: Certainty in Uncertainty