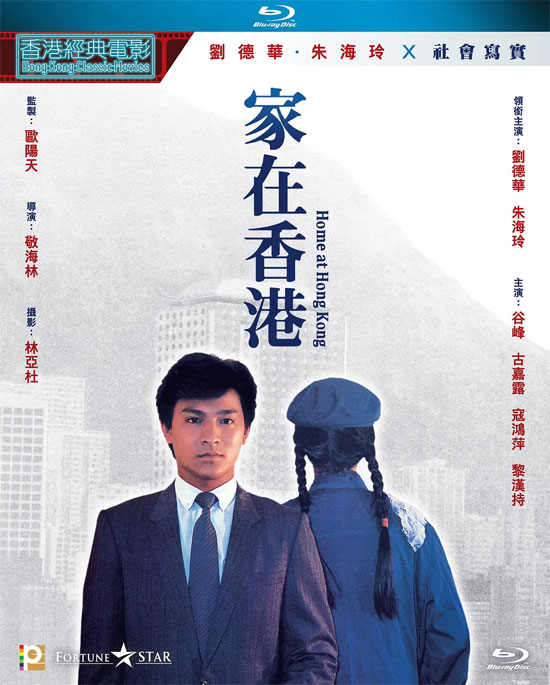

Film Name: 家在香港 / Home at Hong Kong

The film was shot in 1983, just one year after Andy Lau made his breakthrough in the film industry with Ann Hui’s “Home at Hong Kong.” It’s likely that the creative team behind this film chose him based on his performance in “Home at Hong Kong,” as this film shares significant similarities with that earlier work—both are socially conscious, politically engaged pieces. The film tackles numerous political themes: the 1997 handover, the Cultural Revolution, illegal immigration, boycotting Japanese goods, Vietnamese refugees, and more. Particularly striking is its focus on the 1997 handover—at a time when Sino-British negotiations were still ongoing and the Joint Declaration wouldn’t be signed until the following year. The film already grappled with Hong Kong’s future post-handover, revealing astonishing levels of public distrust toward the mainland government among Hong Kong audiences at the time. Ah Fai’s girlfriend Ah Hung’s family represents an ordinary working-class household. Yet after watching television reports on the Sino-British negotiations, they resolve to emigrate—even if it means forcing their daughter to sell her body and abandon her true love. The scene where Ah Fai shouts “What exactly are you afraid of?” after their departure is profoundly poignant.

The film remains most focused on Hong Kong and its people, exposing many of the city’s real-life issues at the time. Hong Kong, just beginning its economic takeoff, bore striking similarities to mainland cities today. Consequently, these historical Hong Kong problems eerily mirror many of our current realities, creating a sense of history reflecting back into the present. For instance, Andy Lau’s character works at a real estate company where someone uses connections to buy seven discounted apartments—despite the one-per-person limit. This mirrors today’s affordable housing scandals. Or take the construction site where Leon Lai’s character works: the contractor rushes to meet deadlines by pouring concrete before reinforcing bars are fully secured—a classic example of shoddy construction. Later, when the boss absconds, workers are left unpaid—a direct parallel to wage arrears for migrant laborers.

Though the film touches on many political issues, it avoids heavy-handed preaching. These contextual elements instead lend the story greater authenticity and emotional resonance, with each main character’s journey leaving a lasting impression. Andy Lau’s character, Alan, represents the struggling young working class. Initially swayed by a motivational speech, he becomes a cosmetics salesman but struggles to make any sales. Later, after a night of passion with Erica—the mistress of a powerful tycoon he met in a bar—he lands a job at a real estate firm through her call. Though his career gains momentum, he realizes he’s merely Erica’s plaything. Only after meeting the kind-hearted Ah Ting, who smuggled herself in from mainland China, does he find true love and resolve to be himself again, leaving Erica behind.

Li Hanchi’s character Ah Fai, a construction worker passionate about boxing, faces an even more heartbreaking fate. The singer Ah Hong he deeply loves marries her boss to fulfill her parents’ insistence on emigrating. Heartbroken, Ah Fai is beaten into a state of dementia while fighting in underground matches. By the time Ah Hong returns to Hong Kong after fulfilling her parents’ wishes, it’s too late to salvage anything.

Gu Feng’s character, Uncle Hu, is another tragic figure representing the kind-hearted working class. He shows deep affection for Ah Lun and fiercely protects Ah Ting when she arrives in Hong Kong as an illegal immigrant. Ultimately, he dies of a heart attack during a confrontation with the police. Two of his discussions with Ah Lun are particularly insightful. One concerns mainlanders smuggling themselves into Hong Kong. As a Hong Kong native, Ah Lun openly admits his dislike for mainlanders, believing Hong Kong was built through the hard work of its people, while mainlanders come to reap the benefits. Uncle Hu counters, “Do you think they get fed without working?” The second concerns the boycott of Japanese goods. Uncle Hu, a humble working-class man, posts boycott posters after learning Japan has revised its history textbooks. Yet Alan, representing the more privileged class, remains completely unaware. Even after finding out, he dismisses it. Uncle Hu retorts, “You Hong Kong people only care about making money. You ignore everything that matters to the nation.”

The final tragic figure is Ah Ting, played by Zhu Hailing—a mainland girl who smuggled herself into Hong Kong, hiding in Alan’s car trunk to evade capture. Initially wary of everyone, she only opens up after realizing Uncle Hu and Alan are good people. After escaping her uncle’s house, she and Alan finally come together. But for the sake of a Hong Kong identity, they risk everything by posing as Vietnamese refugees. With preparations complete, Ah Ting ultimately chooses to return to the mainland to spare Ah Lun from danger. As a symbol of mainland China, the film portrays her with sympathy. Through her final words, it expresses a hopeful vision: “One day, we will have a prosperous, peaceful, free, and open nation.”

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Home at Hong Kong 1983 Film Review: An Overlooked Masterpiece of Realism