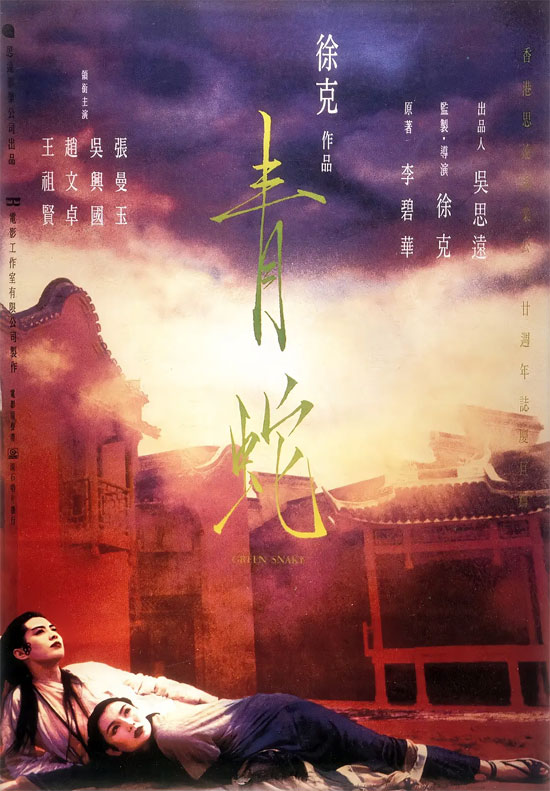

Film Name: 青蛇 / Green Snake

“Green Snake” in Li Bihua’s writing is a story of enchanting passion and intense despair, but when adapted into film, it gained something extra. Beyond the hauntingly beautiful “Liu Guang Fei Wu” and the Indian-inspired yet distinctly Chinese-made “Mahoraga,” a new focal point emerged—Fahai.

In the original novel, Fahai comes across as almost homosexual, seemingly jealous of Bai Suzhen. When he kidnaps Xu Xian, it feels less like a rescue and more like an attempt to claim him for himself. Yet in the film, Fahai transforms into a passionate young man driven to become a Buddha, though his faith continually crumbles.

Initially, this idealistic young monk, driven by the noble ideals of safeguarding national security and maintaining world peace, used his formidable powers to subdue a spider demon. This spider demon had even disguised itself as an old monk doing morning exercises to strike up a conversation with Fahai—what a well-behaved spider demon! But how could our Master Fahai pass up an opportunity to slay a demon? At this point, he judged the morality of beings based solely on their origins: humans were inherently good, while demons were inherently evil. The poor spider demon could only curse her misfortune at being born into the wrong form, denied even the chance to change her social status through her own efforts.

Master Fahai not only imprisoned the spider demon but also crippled its martial arts. The spider demon pleaded desperately, “I haven’t done anything wrong!” But Fahai didn’t even flinch. He then pinned the spider demon beneath a pavilion. His effortless motion made me believe that pavilion was made of foam.

Master Fahai hunted demons far and wide until that rainy night in the bamboo grove, where he witnessed two snakes sheltering a birthing woman from the storm. This time, he hesitated before acting. He recalled the spider demon’s final, innocent wails, and his convictions began to waver. He started to believe demons could possess kindness. So he spared the snakes. But then, he witnessed the woman giving birth! And I too found it strange—wasn’t childbirth supposed to be painful? How could that peasant woman give birth with such grace? Did bearing a child require stripping naked? This truly set the young monk’s blood boiling! Disturbed by this eerie birth, he returned to meditate but couldn’t settle his mind. Demons surged from all directions, and these demons looked uncannily like sperm. Fahai struck out, blasting a few (as if he could eliminate them all with such numbers?), yet the demons kept surging forth endlessly. Fahai’s id and superego engaged in a fierce battle. Fahai understood his purpose clearly: he sought Buddhahood. At this level, he clearly couldn’t attain it—he wasn’t even as virtuous as Liu Xiaohui. Accepting this reality, he prepared for more challenging training.

In our youth, we often cling to pure and beautiful dreams, rigidly rejecting anything that defies our imagination or the hidden rules of society. Yet one day, we inevitably confront that dark and brutal reality, only then realizing how fragile fairy tales truly are. Some cling to their fairy tales until death, while others abandon them to plunge headlong into the grand filth of the world. But Fahai remains undeterred—he vows to protect his fairy tale forever. Buddhism demands purity of the six senses, the abandonment of worldly desires—and so does fairy tales. No need for worldly desires; those in fairy tales never fret over luxury goods. Even Cinderella had a fairy godmother guiding her in secret.

Fa Hai found Xiao Qing, demanding she aid his cultivation, promising freedom if she succeeded. Master Fahai went all out this time—not only seeking the second most seductive creature after a fox, but also retreating to a vast expanse of water for cultivation. For while water may cool the mind, it is also the wellspring of humanity. Who among us did not take shape within our mother’s amniotic fluid? To suppress one’s nature by retreating into water—what lofty moral integrity!

True to form, Fahai failed. Not only did he renege on his promise, but he flew into a rage, blaming Xiaoqing for corrupting his cultivation. Perhaps having a demon witness his humiliation left him utterly disgraced. Fueled by this anger and hidden shame, Fahai became even more convinced that demons were inherently evil. He projected onto demons the blame that should have fallen upon himself. While appearing more resolute, his faith was in fact teetering on the brink. His release of the Spider Demon revealed his increasingly blurred judgment of human and demonic, good and evil.

Fa Hai stubbornly believed Bai Suzhen’s seduction of Xu Xian was an unforgivable crime, so he abducted Xu Xian. I suspect he was triggered by the scene, recalling how Xiaoqing had once tempted him into breaking his vows. Subconsciously, he identified Xu Xian with himself, seeking solace by rescuing Xu Xian. By this point, Fahai was no longer pure; he had developed a sense of “self,” which contradicted the Buddhist principle of selflessness. Fa Hai abandoned Xu Xian in the gloomy Golden Mountain Temple, drowning him in the monotonous drone of chanting that sounded like a swarm of flies. He sought to purify himself through this method, yet found it insufficiently intense. Thus, he rushed to confront Bai Suzhen in battle, believing he could slay his turbulent ego in one fell swoop.

But when he witnessed Bai Suzhen giving birth to a child, his faith shattered completely! “The White Snake gave birth to a child! Could it be that the one I’ve been battling all this time is actually human!” Indeed, he was confronting a human—human nature. The film’s opening scenes depicted humanity in a chaotic frenzy, indistinguishable from demons. Fahai failed to understand that kindness knows no bounds; demons can be benevolent, and humans can be wicked. His single-minded pursuit of eradicating evil inadvertently persecuted goodness. When he realized this, his faith began to swing like a pendulum. He himself harbored evil, while demons possessed goodness—both are called human nature. Fahai fought against heaven, against demons, but ultimately, he was only fighting himself. The film’s intense battle scenes are the materialization of Fahai’s internal struggle.

His pendulum finally came to rest with the words, “Bai Suzhen, I come to aid you.” He had acknowledged that kindness resides within demons, thus overcoming racial prejudice. Fahai ascended to a new level of cultivation, understanding the meaning of equality among all beings. Therefore, when Xiaoqing killed the ungrateful, heartless, and shameless Xu Xian, Fahai did not execute her on the spot. Perhaps he felt relieved that the evil “self” had been slain, bringing him one step closer to Buddhahood.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Green Snake 1993 Film Review: A Monk’s Inner Struggle