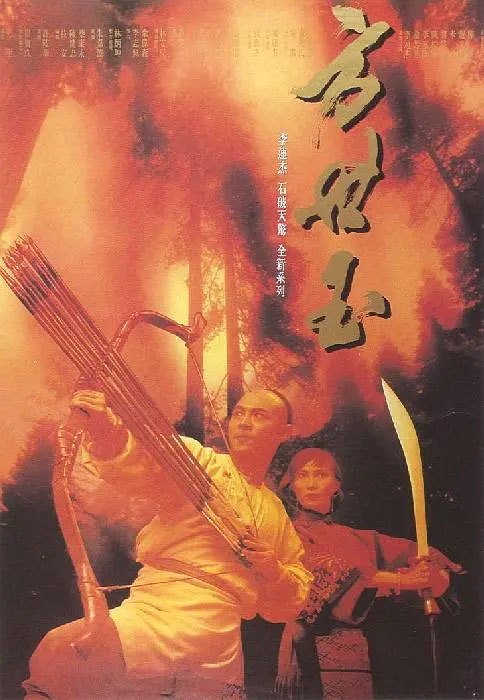

Film Name: 方世玉 / Fong Sai Yuk / The Legend / The Legend of Fong Sai-Yuk

When I saw this 90s martial arts film on TV for the umpteenth time in early October, all my earlier thoughts about the Hongmen mythological genealogy instantly vanished into thin air… Miao Cuihua’s outfits were just too adorable.

According to the earliest vernacular novel about Fang Shiyu, “Wan Nian Qing”—also grounded in Hongmen genealogy—the dramatic conflict designed for Fang Shiyu pitted him against antagonists like Lei Laohu/Li Xiaohuan/Li Bashan, who were non-Cantonese. This contrast itself is quite thought-provoking.

Although the original text set the conflict in Hangzhou, both factions bore distinct marks of Guangdong regional ethnicity. However, the adapted film transformed the razor-sharp tension of the novel, nearly erasing ethnic traces and even making efforts to blur the lines between the two camps.

Notably, this antagonistic dynamic persists in the costumes of the female characters. While Li Xiaohuan wears relatively traditional Han-style attire—a long, slanted-collar robe over trousers, with embroidered collars and hems (a consistent style throughout the film, also seen on her daughter Lei Tingting)—Miao Cuihua’s outfits are distinctly different. Excluding her male disguise, Miao Cuihua changes her attire three times: 1. Selling cloth at the fabric shop, 2. Everyday homewear (including Fang Shiyu’s cross-dressing outfit), 3. Her ceremonial attire at Fang Shiyu’s wedding. Each of these three outfits invariably retains the same defining feature—a short top paired with a long skirt. More specifically: a high-waisted, wide-sleeved blouse with a collar, paired with a pleated long skirt, a colorful apron tied at the waist, and colorful embroidered patches sewn onto the sleeves and apron. The waistband is woven.

This is most prominent in Miao Cuihua’s formal attire, where the embroidered patches on the blouse extend from the cuffs all the way to the shoulders. while Li Xiaohuan wore a front-opening blouse with embroidery directly on the brocade fabric, featuring embroidered edging along the garment’s borders.

Further examination of their hairstyles reveals that Li Xiaohuan and her female companions wore braids with a center parting, whereas Miao Cuihua secured her hair into a bun at the nape with hairpins. (My observations have not yet extended to costumes in other films featuring Miao Cuihua as the protagonist.)

Although the overall differences in their attire are striking, this alone can only suggest their respective ethnic affiliations. However, when we place these costumes within the primary settings of the drama and the narrative framework of the “original text,” certain insights begin to emerge.

It can be observed that all of Miao Cuihua’s costumes in the drama feature blue fabric as their base material, differing only in shade (the lightest shade, closest to sky blue, appears when selling cloth, while the darkest shade, approaching navy blue, is worn for formal attire). Her first scene takes place in a cloth shop. Subsequently, her husband Fang De works in silk sales. The fight scene—second only to the climax in importance yet establishing the entire narrative thread—is set in a dyeing workshop (the sequel follows suit). Thus, the Miao family’s deep connection to dyeing, weaving, and the textile trade is undeniable. Simultaneously, in the late Qing-era “Wan Nian Qing” tales, storylines involving Fang Shiyu also unfold against the backdrop of Guangzhou’s loom workers’ lives.

So, does this ethnic narrative also tie into the so-called “germs of capitalism”? Though melodramatic, it cannot be dismissed. Now, let us examine Miao Cuihua’s primary attire, which can be summarized in four words: short top, long skirt. Naturally, the top features wide sleeves, while the skirt is pleated. Ethnographic research reveals this description has long characterized the traditional dress of Lingnan women—though in relatively recent times, it was applied to groups beyond those touting “Sinicization.”

Concurrently, as mountainous regions were developed and indigo cultivation spread into these areas, certain mountain communities became specialized indigo growers within the regional market division of labor. Later groups like the Blue-Indigo Yao and certain She minorities in the mountains were the inheritors of this craft. As cultural assimilation deepened, while identity transformations occurred, certain occupational skills and associated industry monopolies stubbornly persisted alongside specific cultural traits of these groups.

Thus, Miao Cuihua’s professional characteristics, family background, work environment, and her “short top and long skirt” attire can be readily interpreted as a continuous and unified representation. However, I have no intention here to further unravel the subtle ethnic metaphors within the drama.

Since the 19th century, the rapid economic ascent of Guangzhou and Lingnan has left cultural transformation struggling to keep pace with economic expansion. The rise of handicrafts, the formation of material production and division of labor systems, and accelerated shifts in ethnic relations have all left their imprints on the era’s “cultural stratum.” The southeastern mountainous regions and river deltas where the Hongmen originated also flourished, seemingly driven by an economic fabric centered around dyeing and weaving industries. This may explain why indigo dyeing scenes frequently appear in Hong Kong martial arts films rooted in the Hongmen mythological genealogy.

While the children of Fong Sai-yuk and Lei Ting-ting may no longer wear “short jackets and long skirts,” the cultural threads will persist in more subtle forms, leaving their enduring influence.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Fong Sai Yuk 1993 Film Review: Short-sleeved blouse and long skirt Miao Cuihua