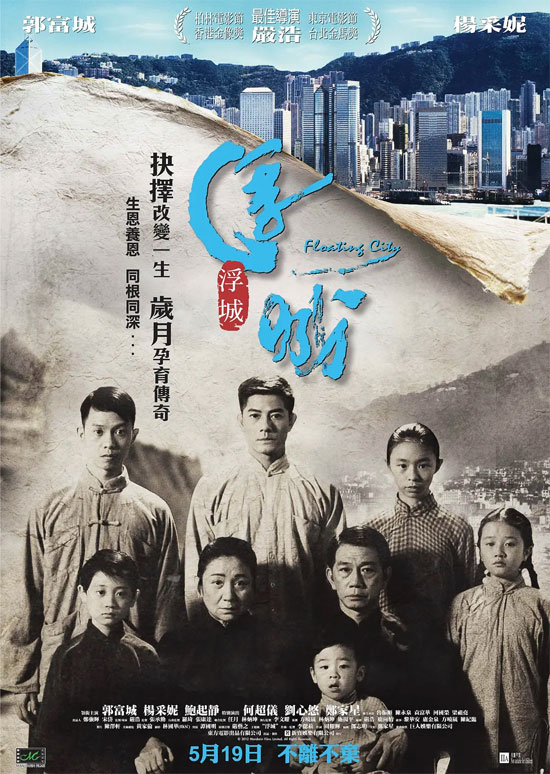

Film Name: 浮城大亨 / Floating City / Hundred Years of A

“Floating City” premiered in 2012, directed by Hong Kong filmmaker Yim Ho and starring Aaron Kwok, Pauline Wong, and Yang Cai Ni. Based on a true story, the film follows Bu Huaquan, an abandoned Sino-British child adopted as an infant by a fishing family living on the water. These waterborne people lived in hardship, held lowly status, and were derogatorily called “egg-shell people.” Through arduous work-study efforts and relentless struggle, Bu Huaquan eventually became the first Chinese chief clerk of the British East India Company. The film not only portrays a legendary figure and the tumultuous history of colonial Hong Kong but also tells a heartrending story of mother-son affection, rich in meaning and deeply moving.

The opening narration states: “We are Dan people, living inside eggshells.” The Dan people made boats their homes; the “eggshells” referred to their living vessels, shaped like eggshells, symbolizing the fragility of their existence. If starting from scratch represents the baseline for ordinary people’s struggles, then as a Dan person, Bu Huaquan’s starting point was below the waterline—lower and more humble than anyone else’s. Through understanding the Danjia people, audiences will rediscover numerous details in the film, gaining deeper appreciation for its artistic resonance and emotional depth.

The Danjia people, also known as the Tanjia or Danjia, are described in Zhou Qufei’s Song Dynasty text Ling Wai Dai Da · Man: “Taking boats as homes, viewing water as land, those who float their lives upon rivers and seas are the Dan.” This glimpse reveals their ancient origins. Their lineage likely traces back to the early inhabitants of Nanyue who settled along the coast, relying on fishing for sustenance. Over generations, land-dwelling residents fleeing persecution, war, or forced labor took to the seas, mingling among the boat people. They drifted with the fishing seasons, scattering across Fujian and Guangdong.

Historically, the Dan people were often grouped with the mountain-Shaanxi entertainment households, Zhejiang’s fallen commoners, Jiangsu’s beggar households, Jiande’s Nine-Surname fishing clans, Huizhou-Ningguo’s hereditary serfs, and general servants and constables as outcasts. Their trade passed from father to son; the imperial court barred them from imperial examinations, and commoners shunned marriage with them. Qing dynasty scholar Yu Jiao’s “Chao Jia Feng Yue Ji” records: The Dan households… take boats as their homes, marry among themselves, and are despised by all.” The Yongzheng Shilu (Volume 81) records: “The people of Yue regard the Dan households as an inferior class.” Thus, the term “Dan people” carries a derogatory connotation when used by outsiders, often replaced with euphemisms like “boat dwellers” or “water people.”

Local chronicles throughout the ages recorded: “Clothes barely covered their skin,” “rarely had a full meal”; “poverty and cold afflicted them more than peasants elsewhere”; “rivers and seas were their fields, boats their homes”; “endlessly selling off possessions, mortgaging wives and children in disgrace,” and so on. Such historical depictions persisted even under British colonial rule in Hong Kong, etched into the fate of Bu Huaquan and his forebears. On stormy seas, a mother nearing childbirth, her belly heavy, still helped row the oars, causing a miscarriage. Thus, her eldest son, Bu Huaquan, was adopted. On a neighboring boat, Aunt Shi’s family had no grain left. When a typhoon arose at sea, they still insisted on setting out. After eating the last rice meal borrowed from the Bu family, Aunt Shi took her childhood sweetheart, her young cousin, and steered the boat into the sky, never to return. A-di, a young lover, became a “scrap collector,” gathering leftover food scraps from ships passing through Hong Kong for resale. She used these scraps to supplement her family’s meager meals. After her father perished at sea, her mother, unable to support them, sought help in vain. She had no choice but to place her three older children in a Christian charity school and give away her two youngest.

The Tanka people lived on boats, rarely settling ashore. Compounded by social discrimination and oppression by the powerful, “the Tanka households dared not confront the common folk, cowering in fear and enduring humiliation, confined to their boats, never experiencing the joy of settled life” (Yong Zheng Shi Lu, Volume 81). Thus, most Tanka people dared not venture ashore to seek a livelihood. For these waterborne communities, “going ashore” signified attempting a different way of life—escaping and altering their current status. Ah Di’s cousin went ashore to work in a plastic factory; Pastor Ah Dong suggested Bu Huaquan go ashore to study and learn to read. Her mother sighed, “Who wouldn’t want to go ashore?” but her father cut her off before she could finish. Should one follow in their father’s footsteps, content with tradition, or take risks to forge a new path? This very question of embracing or rejecting “going ashore” is the root of the generational conflict between the two generations of the Tanka people.

The fear and rejection of “going ashore” have, to some extent, contributed to the Tanka people’s isolation and their generations-long decline. This is reflected in education: records from the Xianfeng era in the “Shun De Xian Zhi” (Volume 6) mention “those who cannot read or write,” and even state “they do not even count their age.” Through Pastor Adong’s efforts, the now-grown Bu Huaquan finally sat in a primary school classroom, where he faced curious teasing from the children. Eventually, due to complaints from other parents to the principal, Bu Huaquan could no longer attend as an auditor. Parents surrounded the silent Bu Huaquan, demanding, “Do you Dan people even have surnames? Surely you don’t lack even that?” This reveals both the isolation of the Dan people and the prejudice of the general populace.

The Shun De Xian Zhi (Volume 2), compiled during the Jiaqing era, records: “Only the women of servants, Yao, Tan, and guest settlers go barefoot year-round, more so than the sturdy-footed men.” The film faithfully recreates this detail of barefoot boat dwellers: in the opening scene, when the mother adopts Bu Huaquan at the Tianhou Temple, there are no close-ups of feet; Later scenes, shifting perspectives, consistently show women and children moving barefoot. When Ah Dong later enrolls Bu Huaquan in a literacy class run by the neighborhood welfare association and gifts him his first pair of shoes, it feels like completing a rite of passage. For Bu Huaquan, a descendant of generations of Danjians who eked out a living on the sea, wearing shoes for the first time while learning to read marks his ascent onto solid ground.

Like the Shaoxing Lotus Songs originating from beggars and blind street performers, the floating Tanka people also have their own fishing song culture—the Saltwater Songs. “Buying wood, unaware it’s rotten inside; choosing people is easy, but finding a brother is hard—where’s my brother?” ” Scatter embroidery needles along the road, finding needles is easy, finding a sister is hard—where is my sister?” After years of struggle, Bu Huaquan, who ultimately gained British citizenship and ascended to high society, also grapples with crises of identity and values. “Who am I?” “My sister’s heart dwells in hell, and I created that hell for her. I am everything good, but I am not a maker of hell.” As Bu Huaquan sings the saltwater songs anew, he finally finds inner peace.

Upon first viewing “Floating City,” I wrote this review: “What moves me most is genuine emotion. Life is full of hardship—love your parents, love your wife, love your children. Love tirelessly, shedding tears and striving with all your might. Amidst the world’s coldness and warmth, a noble person must strengthen their resolve and endure all past humiliations. Not for future vindication, but to honor the hardship of creation and the suffering of loved ones.” The opening narration: “We egg people are so fortunate to have witnessed all the most beautiful sunsets.” Hearing it again, tears fell like rain.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Floating City 2012 Film Review: The Egg Family’s Lowly Servants