Film Name:狄仁傑之四大天王 / Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings

This July, Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings will undoubtedly have a spot on my must-watch list—the name “Tsui Hark” alone is reason enough.

From 2010’s “The Kingdom of Heaven” to 2013’s “The Dragon King of the Divine Capital,” and now this year’s “The Four Heavenly Kings,” a “fantasy universe” of Di Renjie—existing between reality and the supernatural—has taken shape. One must admit, certain themes and elements are not something just anyone can pull off.

First, the conclusion: Despite its flaws, I’m generally inclined to give it a positive review.

Now, let’s talk about “The Four Heavenly Kings.” We’ll start with the shortcomings before highlighting the strengths.

[Friendly reminder: Spoilers ahead.]

Regrettably, despite reaching its third installment, the “Detective Dee” series still peaks in overall quality with its first film, The Mystery of the Phantom Flame. It excels in suspenseful plot devices, character conflicts, and its portrayal of extraordinary individuals, ranking among the upper-middle tier even within Xu Xiaoyong’s entire directorial body of work.

In contrast, Rise of the Sea Dragon pales in comparison overall, while The Four Heavenly Kings continues the trend from its predecessor: further “subtracting” from the film’s structural integrity and narrative richness.

Character development and relationships have always been key factors determining a work’s quality. Currently, The Four Heavenly Kings stands as the weakest entry in the series. Setting aside the difficulty of character breakthroughs, the filmmakers could have focused on exploring the complex emotions of the characters. Yet the tension between Yuchi Zhenjin and Di Renjie—the only pair whose relationship offered any real substance in this film—fizzled out completely halfway through…

The film’s main plotline barely qualifies as “suspenseful.” Throughout, there’s almost no sense of tension. The initial conflict stems from Wu Meiniang’s “tantrum” over Emperor Gaozong’s gift of the Dragon Scepter—though it’s understandable that the Empress would harbor imperial ambitions, and it’s later revealed she was manipulated by a sorcerer… it all feels a bit too formulaic.

As for Di Renjie’s investigations, they become routine white rice—methodical (following clues to the hilt) and lacking in surprises (barely any spark). Plain fare is indeed essential, but when you finally cook a meal, at least add some sauce for flavor.

Conversely, the side dish meant to spice things up feels overloaded… Yes, I’m talking about the romantic subplot between Shatuo Zhong and Shuiyue.

Honestly, these two serve multiple purposes: delivering most of the film’s laughs, enriching the dynamics between the Xiren faction, the Dali Temple, and the Fengmo clan, and adding a layer of warmth through their shared Tiele ethnicity.

Yet strong “functionality” doesn’t equate to high “compatibility.” Setting aside Shatuo Zhong’s abrupt “rapid progress” in this relationship, take Shuiyue’s character—her backstory offered immense potential, yet her actual portrayal always felt lacking. Her complexity falls short of Shangguan Jing’er in The Mystery of the Phantom Flame, while her functional impact pales compared to Yin Ruiji in Rise of the Sea Dragon—a genuine disappointment.

Equally disappointing is the pivotal artifact, the Dragon-Raising Mace. While it serves as both the catalyst for The Four Heavenly Kings’ narrative and a crucial plot thread, it merely fulfills its basic function…

…but its “accompanying mechanics” feel half-baked. According to the original design, the Dragon-Raising Mace could identify weaknesses in other weapons through combat and exploit them—in other words, it’s a weapon that requires a certain level of strategic intelligence to wield effectively.

The film’s treatment of the Dragon Scepter is far more simplistic, reducing it to an indestructible, weapon-shattering, illusion-dispelling all-purpose divine artifact—a simplified version of “Divine Weapon Mysteries”…

This approach aligns perfectly with the film’s style of boldly cutting ideological depth and complexity.

However, what truly left me feeling awkward was the film’s overall tone. The oft-repeated phrase “Until hell runs dry, I vow not to become a Buddha” feels more like a guiding concept—to put it plainly, the conflicts and core themes of The Four Heavenly Kings could be summed up with “When will this cycle of vengeance end?” A world filled with hatred and desire is hell itself. To transcend this, one must undergo a purification akin to “laying down the slaughtering knife and attaining Buddhahood instantly.”

Personally, I admire those who achieve enlightenment by letting go of hatred. Yet, extinguishing others’ rage from a moral high ground feels somewhat like “spending someone else’s money,” especially when it comes to blood feuds like those involving the Demon Sealing Clan (though, admittedly, the Demon Sealing Clan has escalated to terrorism, which I don’t condone).

What’s even more baffling is that Master Enlightened One, who single-handedly turned the tide, didn’t resolve the conflict through profound Buddhist teachings but with illusions even more potent than the Demon Sealing Clan’s (at least in my view)—akin to “Give me some damn peace!” Isn’t that just fighting fire with fire? Though admittedly, it worked…

After the credits rolled, “The Four Heavenly Kings” tacked on three post-credits scenes in the style of “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2” to patch up the story, barely stringing the three films together as a “trilogy.” Wu Meiniang’s Buddhist prayer scene hinted at “Hell never empties,” whether this elevates the narrative or devolves into absurd rambling is left to the audience’s interpretation.

Now, moving past the flaws to the merits.

Despite the film’s narrative flaws, “The Four Heavenly Kings” is visually impeccable. Costumes, styling, props, and special effects all shine with a vibrant yet tasteful aesthetic, masterfully balancing light and shadow.

Take the costumes alone: across the trilogy, Wu Meiniang’s ensembles have consistently dominated Chang’an Fashion Week as must-have trends. These pieces could easily grace national runways with any model—a uniquely dazzling (if slightly jarring) experience that’s genuinely rare. For context, compare them to Carina Lau’s looks in the recent “Asura”…

Xu’s mastery of aesthetics also shines through in his character design.

I hadn’t really noticed Ma Sichun’s beauty before, but while watching the movie, I found myself raising my eyebrows in surprise. With just a few styling tweaks, she could embody so many different looks—now I realize Tsui Hark is truly one of the filmmakers who best understands how to make women look stunning on screen.

But if it were just about “surface appeal,” my rating for The Four Heavenly Kings probably wouldn’t be very high… The key lies in the fact that Old Monster is a shrewd filmmaker—he knows exactly what he wants and what he can achieve.

While I’ve criticized several aspects of the film’s watchability, to be fair, “The Four Heavenly Kings” delivers a relatively complete narrative (neither overly complex nor lacking substance), and the actors deliver solid performances (Di Renjie is courteous and strategic, Weichi Zhenjin fumes and lashes out, while Wu Meiniang endlessly courting disaster), even if not entirely satisfying, all serve the film’s purpose.

Tsui Hark is a director who prioritizes technical execution. His acclaimed masterpieces often emerge when hardware is sufficiently assured, allowing him to add the finishing touches at the software level—hence why we sometimes criticize the Old Monster for weak stories or unengaging films, but rarely complain about his special effects being subpar or lacking spectacle.

After “The Mystery of the Phantom Flame,” Tsui faced two paths: one emphasizing suspense and deduction to create a Tang Dynasty-era “Detective Dee” series, the other focusing on supernatural elements to craft fantastical tales blending reality and illusion.

Judging by the actual results of “Rise of the Sea Dragon” and “The Four Heavenly Kings,” Tsui clearly chose the path that was both easier and more suited to him.

“Domestic fantasy films” constitute a genre with inherently weak foundations and chronic underdevelopment. Few have succeeded in this realm, making it nothing short of a miracle that Old Master Tsui has persisted to this day. In my view, his greatest brilliance lies in striking the perfect balance between reality and illusion.

From the self-immolating curse and the deer-bodied royal advisor, to the humanoid Dragon King and deep-sea monsters, all the way to the golden dragon’s resurrection and the clash of gods and demons… every seemingly fantastical phenomenon is actually rooted in “bizarre techniques” like poisonous charms, ventriloquism, exotic beasts, and esoteric arts. In other words, even the most fantastical elements can be stretched to fit a scientific explanation.

This “offensive and defensive” approach effectively alleviates the subtle psychological burden for materialist audiences—allowing them to fully immerse themselves in what is clearly ‘fake’ while still enjoying it as if it were “real.”

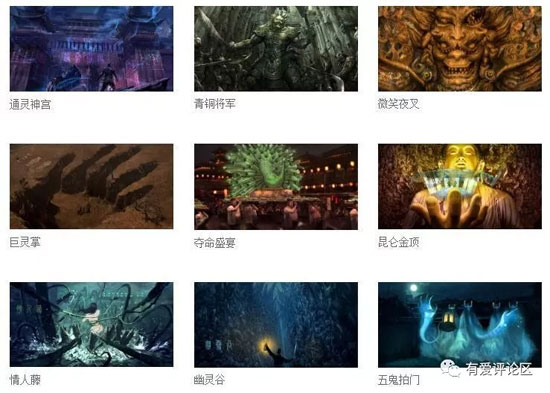

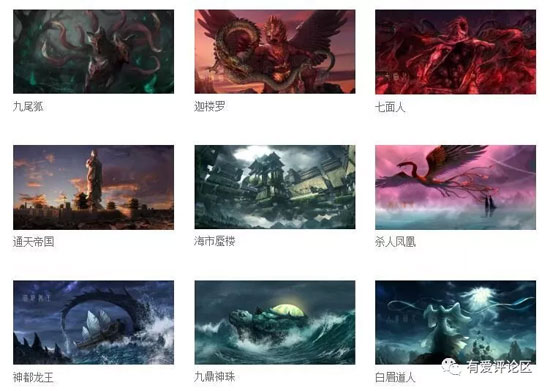

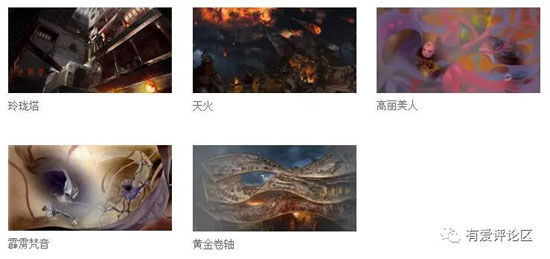

As early as the release of “Rise of the Sea Dragon,” Tsui Hark unveiled 23 thematic concept artworks for the Detective Dee series.

The currently screening “The Four Heavenly Kings” clearly bears the imprint of Garuda.

China is not lacking in source material for magical/mystical/fantasy narratives—ancient myths, Investiture of the Gods, Classic of Mountains and Seas, Journey to the West, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio… The list goes on, yet truly well-executed genre films remain scarce. In recent years, it’s been unrelated prototypes or IPs like Detective Dee and Mummy’s Tomb that have delivered outstanding performances.

Upon reflection, this success might stem from their refusal to chase “grandiosity” at all costs, instead opting for meticulous craftsmanship within relatively “compact” frameworks.

This likely explains why audiences remained supportive even after the significant decline in quality seen in “Rise of the Sea Dragon”…

“The Four Heavenly Kings” shows both regression and improvement compared to its predecessor… I sincerely hope Tsui Hark continues the Detective Dee series. The ‘essence’ is now established; I only pray for an added touch of “spirit” in future installments.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Detective Dee: The Four Heavenly Kings 狄仁傑之四大天王 2018 Film Review: Come on, let’s tell a fantasy story using “science.”