Film Name: 勇敢传说 / Brave / Bear and the Bow

If I were to rank the highlights of this film, I would say they are as follows: First, Merida’s highly distinctive, intensely textured red curls; second, the soundtrack; third, the film’s interpretation of so-called “bravery”—the courage born of deep mother-daughter affection to shoulder responsibilities and mend rifts; fourth, the three mischievous yet charming little boys.

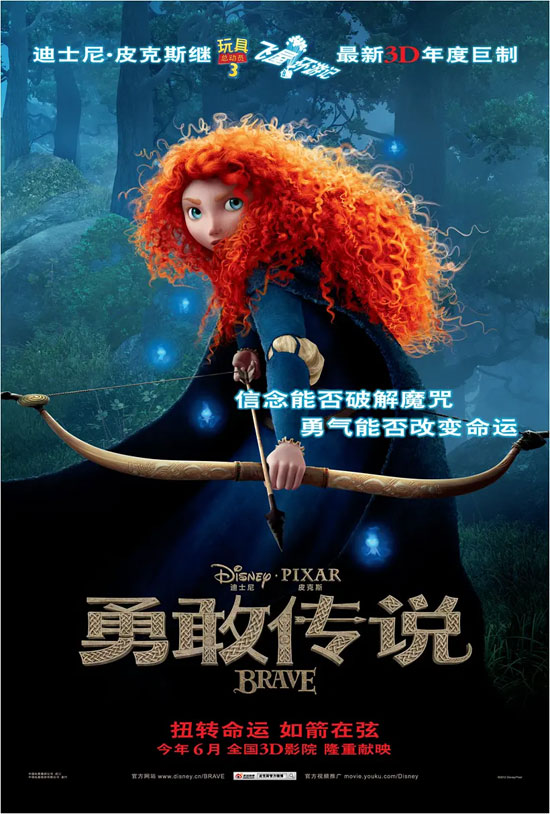

From the moment I first saw the posters and stills for Brave, I sensed that the value of its character design, in a certain sense, surpassed the thematic value of the film itself. To be more specific, the significance of the protagonist’s curly, textured, and perpetually eye-catching red hair to this film outweighs everything else. This bold yet composed red mane serves as both a visual identifier for the heroine and a symbol of her character. This mane of red hair endows the character with extraordinary recognizability, making her stand out like a crane among chickens. It becomes the reason why her dolls fly off store shelves, transforming her into a new fashion icon in the minds of girls worldwide. It grants her a level of originality increasingly rare in contemporary animation. Paired with the heroine’s heroic pose drawing her bow and arrow, she instantly becomes a vivid, living character.

No amount of artistic expression devoted to this red hair would be excessive. As some film reviews have noted, when facing allies or formal occasions, Merida’s mother deems her red hair incompatible with the image of a proper young lady and insists on covering it with a cap. Yet Merida stubbornly lets a tuft of red peek out, vividly conveying the rebellious spirit embodied by her hair to the audience. Yet, my slight disappointment lies precisely with Merida’s red hair. Is it merely for visual effect? Is its sole purpose to differentiate Merida from conventional protagonists? We saw a similarly hair-focused heroine in Tangled, where her golden locks served not only as a visual marker and personality trait but also as a functional tool. Merida’s red curls, however, remain purely ornamental. Why they’re curly? Why that specific length? Why even red? None of it feels essential. We know that in the finest films, every prop, every design choice, every detail is purposeful.

The film’s score is truly remarkable—it delivers a sense of sudden clarity when the scene calls for brightness, and an air of mysterious depth when gravity demands it. Particularly striking is the Scottish bagpipe music playing as the allies enter the king’s hall, instantly transporting you to a foreign land and placing you right in the heart of the film’s setting.

Regarding the film’s central theme of “Brave,” I feel its portrayal falls slightly short. If the protagonist’s level of effort—both physical and mental—is what defines bravery, then nearly every American animated film could be renamed Brave. Whether exploring the unknown path guided by mysterious spirits or courageously confronting her father and a vicious bear to protect her mother, these actions seem far too commonplace. Any protagonist should possess this awareness and take such actions without hesitation. After finally breaking free from the confines of her family, she gallops alone through the forest with a beautiful foal—only to discover it’s all for a remedy to change her mother’s attitude. Before long, she’s back where she started.

This reminds me of the film “War Horse” I saw earlier this year. If we’re talking about bravery, that’s what true courage should look like. The protagonist should at least face genuine life-or-death situations, and should be separated from home—that sanctuary of the heart—for a significant period of time. Otherwise, how could he break free from familial protection to achieve true independence and growth? And without that independence and growth, how could we speak of bravery? You might argue Merida is sufficiently independent and mature. But note how she handles family conflict: she seeks to alter her mother’s attitude through a witch’s magic. In other words, she aims to change others rather than herself. This isn’t a sign of complete independence or growth, nor does such logic qualify as bravery. In fact, compared to Merida, I find her queen mother far braver. Not only did she dare to battle the enchanted bear, but she ultimately dared to change her own perspective.

Regrettably, Merida’s journey never truly took her beyond the harbor of her family. Her shift came solely in her attitude toward family—from resenting her mother’s meddling, lack of understanding, and arbitrary decisions, to gradually recognizing her mother’s love. This falls far short of what we might call true inner courage. Still, the film’s portrayal of the mother-daughter bond remains exceptional. Through a clever narrative device, the film allows both mother and daughter to understand each other’s deepest thoughts. The mother comes to recognize her daughter’s yearning for freedom as a legitimate desire, and that freedom truly brings her joy. The daughter, in turn, realizes that her mother’s constant reprimands stem from love, and that life without her mother is unimaginable. Thus, the film’s central tension never lies in whether the mother can break the spell binding her, but rather in when the daughter will grasp these truths and how she will express them to her mother. Bathed in the glow of the morning sun, this confession proves profoundly moving.

Here, if we carefully consider the director’s interpretation of “bravery” and the motivation behind naming the film with this word, we discover that Merida’s skilled archery and her free-spirited, daring personality are merely superficial expressions of courage. True bravery lies in how she confronts her mother and the fractured bonds of family. The courage the film truly portrays lies in the willingness to shoulder responsibility and mend fractures born from deep maternal love.

The film offers few laugh-out-loud moments, with most of its humor stemming from the triplet boys. I once identified seven types of animated characters beloved overseas, with mature child prodigies being one category—the triplets were crafted precisely for this archetype. The penguins in “Madagascar” share a similar charm.

Here I’d also like to discuss two highlights in the film that feel somewhat flawed.

One is the sequence involving Merida and the witch. This scene has a very strong animated feel—not only is the pacing brisk, but it’s also incredibly imaginative. Many draw parallels between the witch herself and Yubaba from Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, noting their visual similarities. To me, what truly echoes Miyazaki’s animation in this sequence is the witch’s home decor—a collection of wooden bear carvings and an abundance of imaginative visual symbols suddenly filling your field of vision, much like stepping into Haku’s bedroom. This sudden surge of imaginative imagery is characteristic of Miyazaki’s approach to world-building. Even though the witch and Yubaba look vastly different, with no obvious traces of inspiration between them, the way imagination is expressed in the witch’s home is distinctly Miyazaki-esque—and that connection is the more fundamental one.

Yet Merida’s interaction with the witch ends with that encounter and a brief follow-up; the witch never reappears in the film. The story concludes with the witch attending a music festival as her ultimate fate, which is extremely abrupt. This renders the meticulously crafted witch’s home, her affection for bears, and characters like the crow utterly worthless, suddenly transforming them from brilliant elements into rootless trees. Audiences need a reason for the witch’s existence, as she embodies an entirely new worldview—fantasy. What defines fantasy? Is it merely sprinkling magic? As Pixar’s first purported fantasy film, failing to deeply explore the witch’s character, to weave her meaningfully into the protagonist’s journey and the plot, and to ground every detail surrounding her in purpose or resonance—how can this be called fantasy? This is a significant regret.

Another standout yet underdeveloped element is the fate of the ancient prince transformed into a bear. When he finally becomes a fae spirit and flashes Merida a liberated smile, I was utterly stunned. This concept is one of the film’s most brilliant ideas. It not only indirectly reveals the origin of the Fae and why they can guide travelers but also completes the humanity of the film’s antagonist. However, the regret lies in the fact that it happens without any foreshadowing. Because the Bear was so utterly evil, and the ancient prince was portrayed as a world-dominating tyrant, his final knowing smile lacks sufficient moral justification.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Brave 2012 Animation Film Review: Is this level of courage really brave?