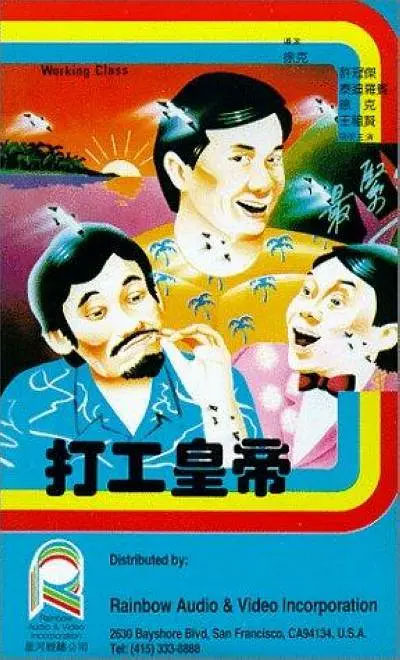

Film Name: 打工皇帝 / King Worker / Working Class

Remember Hong Kong in the 80s?

My entire impression of 80s Hong Kong comes from movies. The golden age of Hong Kong cinema preserved what the city looked like back then. Just as Chun Fung Street in “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Father!” captured 60s Hong Kong, and “Front Page” captured the 70s, this film “King Worker” also preserves the look of 80s Hong Kong.

One scene that struck me deeply involves the protagonist’s friends visiting their boss’s villa, trying to create an illusion of wealth for him—”to be rich for a day.” Beyond the mockery lies a bitter truth: the wealthy live in mansions with ten servants, while factory workers barely scrape together enough for meals, their labor rendered worthless when factories shut down without warning.

When Sam Hui was broke, he turned to underground boxing. The symbolism was stark: either abandon dignity for money, or preserve dignity and walk away.

So don’t mistake old Hong Kong cinema for simplicity. Don’t dismiss it as crude just because the acting seemed exaggerated, the props rudimentary, or society less developed than today. The truths and tactics conveyed were often more profound than in contemporary films. Those directors saw clearly and wielded their craft with mastery. Beneath the playful facade, they distilled the full spectrum of human experience.

Among the film’s many small characters, another who left a deep impression was Tsui Hark’s girlfriend—sharp-tongued but soft-hearted. Every role felt fully realized, showcasing the skill from script to performance. This wasn’t achieved by throwing money at it—it required a professionalized training system. Shaw Brothers was dubbed the “Shaolin Temple” of the television industry back then. Though the work was demanding and the pay meager, a few years there could make you a master of every craft. It was the teamwork and the established processes that elevated the film industry.

At that time in Hong Kong, with the gradual strengthening of the rule of law, the return of local talent from Britain, and the backing of capital from the first wave of entrepreneurs, the city entered a new era of development. Everyone worked—the lower class in factories, the middle class in companies. Hong Kong’s real estate was still affordable for working people back then; as long as you worked, you could have a place to live. I recall reading in the biography of the music maestro Hu Weili, who went to Hong Kong to pursue his dreams, that in the late 1980s, he purchased a flat. By the time he planned to emigrate before 1997, the property had appreciated several times over, becoming his most successful investment and largest source of income in Hong Kong.

Sadly, as housing prices skyrocketed, Hong Kong cinema entered a period of dormancy following the final peak brought by Stephen Chow.

The middle-income trap not only crushed the city’s drive but also sapped the vitality of Hong Kong cinema.

What draws me to 1980s Hong Kong films is their authenticity—free from heavy political undertones. Back when the city thrived toward a brighter future, everyone could make money and speak their minds freely. The joys and sorrows of ordinary people truly belonged to them, untethered to any specific social structure or system.

Today, I believe Taiwanese cinema reflects our times most clearly—films like The Great Buddha+ and Godspeed. No matter how society advances, there will always be underprivileged groups, persistent poverty, and barriers to upward mobility. Money remains an eternal problem. Yet as society advances, the internet flourishes, systems improve, and infrastructure develops, the underclass may not feel marginalized until critical moments strike—this is society’s flaw. Much like Ready Player One’s vision of the future, the wealth gap widens further, yet the poor show little desire to alter their fate. They can immerse themselves in virtual worlds, order takeout, live in affordable housing, and feel connected to the world through their phones; This illusion shatters only when life demands essentials: no money for medical care, no money for housing. Worst of all, no money means no dignity. Because everyone seems rich and everyone fucking wants to make money—everyone’s fucking crazy. So no one bothers to make good movies or pursue innovation anymore.

Finding good films in the past decade has been rare, unless society undergoes major upheaval. Cinema thrives on social context, but even more on filmmakers’ perseverance. Mainland and Hong Kong’s environments are restless, and filmmakers face too many constraints. When directors like Tsui Hark and Yuen Woo-ping resort to cashing in on old works, what groundbreaking achievements can we expect from the older generation? For great films, we’ll have to wait for the next dynasty (Zhao).

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » King Worker 1985 Film Review: Hong Kong in the 1980s