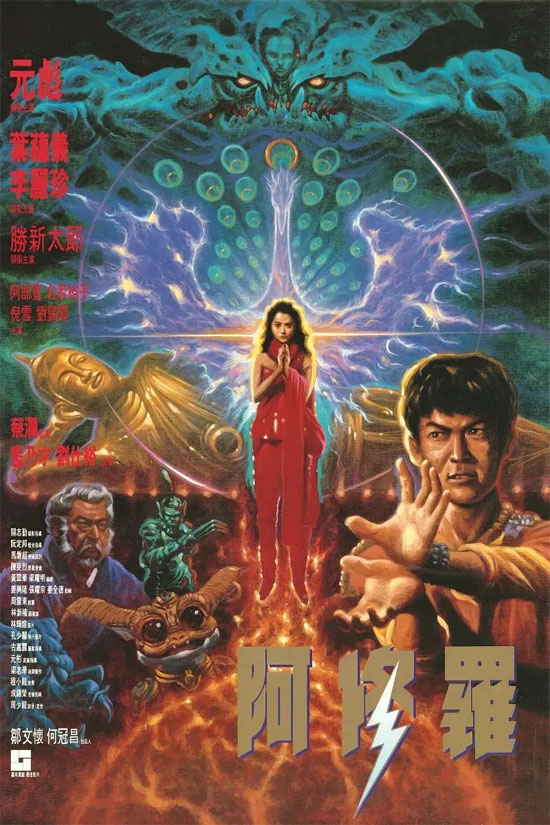

Film Name: 阿修罗传奇 / Saga of the Phoenix / 阿修羅

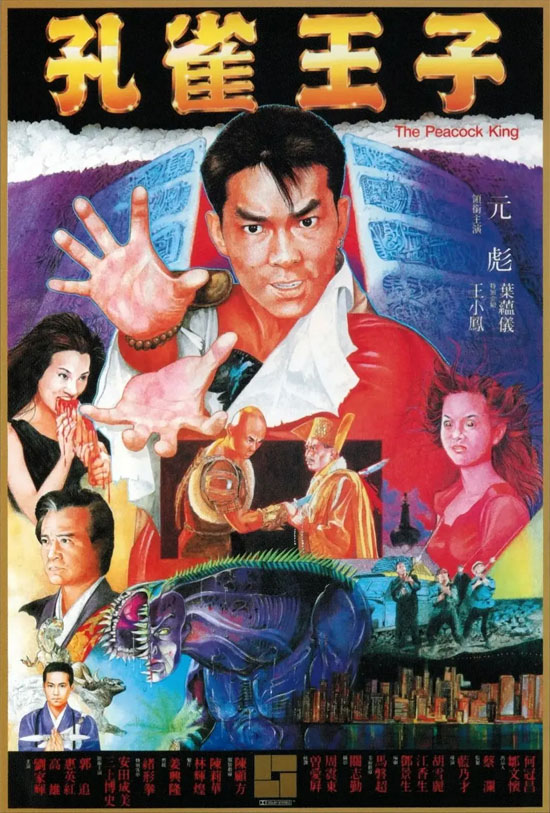

In 1988, the legendary director Lan Naicai, whom I personally admire, directed the Japan-Hong Kong co-productions “Peacock King” and “Saga of the Phoenix.” While these were intended as a series, the two films were actually shot separately with different lead actors—likely to reduce costs. The first film received favorable reviews, so they capitalized on its momentum to produce a sequel, reusing costumes, props, and sets. Unfortunately, lead actor Yuen Biao was too busy to commit fully, appearing only briefly at the beginning and end via frozen footage. The Japanese male lead was also replaced—from star Hiroshi Mikami to model-turned-actor Hiroshi Abe. The supporting actor role switched from Hong Kong’s Gao Xiong to Liu Xixian, while Japan replaced Ogata Ken with Shō Shintarō. Fortunately, the delightful young actress Yip Wan-yee persisted in portraying Ashura, donning her red bodysuit twice—an appearance audiences graciously embraced. The two films premiered in Hong Kong in 1989 and 1990 respectively, running for 9 and 19 days. The first film broke the million-dollar mark, ranking 31st on the annual box office chart—just a hundred thousand dollars shy of the wildly popular “Proud and Confident” starring Andy Lau. The sequel fared much worse with audiences, landing at 45th place on the annual chart with earnings of just over 7 million dollars.

Out of affection for “Peacock King,” I managed to watch both films. Di Ye’s truly twisted sense of humor would have been strictly R-rated if adapted for the big screen. With Hong Kong screenwriters localizing the content, the films essentially became two entirely separate works from the original source material. “Peacock King” featured separate dubbing for the two regions. In the Japanese version, Hiroshi Mikami voiced the exorcist Peacock, while Yuen Biao played the gender-swapped version of Tomoko, renamed Kichikō. In the Hong Kong version, their names were swapped, with the original character labeled as the lecherous Peacock, whose design diverged drastically from the original. Director Lan Naicai’s true genius lies in crafting sci-fi blockbusters using low-tech special effects and models (“Black Cat” is breathtaking). This film opens with Asura’s birth, then has the Six Paths’ Rōga make an early cameo appearance—likely because filming the Great Sage (human form with an elephant trunk) from “Asura” proved too challenging. The opening segment at the department store blessing ceremony is remarkably faithful to the source material (originally set at a TV station). The scene where a demon is pulled from a woman’s neck is superbly executed, perfectly recreating the manga. From there, the director takes creative liberties. First, the Twelve Guardian Generals of Yakushi at Ura-Koyasan become cult followers. While the specific sect remains unnamed, the leader’s attire suggests it’s still Ura-Koyasan. Perhaps they initially planned to follow the source material but, after crunching the numbers, it proved too costly, so they simply invented a new cult. Peacock’s parents were killed by this cult, and Master Liu Jiahui, as the leader of the Twelve Generals, Gong Kunluo, looked absolutely stunning—far more imposing than in the manga. The opening scene of the twelve charging down the road was truly awe-inspiring. Unfortunately, due to budget and runtime constraints, Master Liu had limited screen time. Aside from the sword-slashing scene against Gao Xiong requiring some acting, his final demise—crushed by the Demon King—was entirely achieved with models. Since production was Hong Kong-led, Asura at least wore clothing upon his entrance. The so-called “Gate of Hell” was also set in Tibet. After causing chaos in Tokyo and Hong Kong, the protagonists journeyed to confront the Great Demon King of Hell. Director Lan’s meticulous recreation of the demon palace from the manga is truly remarkable here. Though the transformation of Rōma and the distant palace shots clearly use stop-motion models, the effort is evident. In the manga, Rōma possesses immense combat power, transforming into the half-human, half-snake Aizen Myōō—a beautiful woman clad in armor wielding a celestial bow—effortlessly annihilating the “Earth” division of Rikōyō’s combat unit, the Gorinbō. In the film, she merely kills two reporters before escaping with a severed arm. Her second appearance sees her eliminate several Yakusho Divine Generals before being swiftly vanquished. The manga hinted at a major battle, but Tibetan Tantric lamas discovered only a massive skeleton in the Demon Palace’s coffin. Whether the Demon King vanished or reincarnated remains a mystery to be unraveled later. Director Lan directly pits the heroes against the Great Demon King, ultimately vanquishing him. Honestly, the special effects in this segment far surpass the demon god’s visuals in “The Mad Monk,” showcasing Director Lan’s profound mastery.

The setting of “Saga of the Phoenix” takes place after this film and is entirely detached from the original source material. It roughly depicts Master Cikong preparing to seal Asura, with Peacock and Kichijō opposing him. During this period, the trio battles the demon realm. It can be viewed as yet another tired tale unfolding in a fantasy world. To pad the runtime, the film added interactions between minor demonic creatures and the female lead (likely influenced by Disney’s trope of the heroine needing a pet companion), but this feels out of place and comes across as rather silly. Yuen Biao, likely too busy with other projects, spends most of his screen time frozen. Abe Hiroshi, though famous now, was far less prominent back then. While the addition of three beauties at the women’s hall in Koyasan draws attention, the story remains disjointed, failing to capture the eroticism and violence inherent in the original. The original scene where the peacock spies on the waterfall training at the Kōya women’s hall was hilarious, but having the nuns swim in swimsuits in the film lost the essence. The ending is even more open-ended: Asura wanders the world, and it’s hard to imagine a witch capable of unleashing world-destroying firepower, dressed in bright red, blending into crowds everywhere.

PS: Though “Peacock King” and “Saga of the Phoenix” failed to capture even a fraction of the original’s essence, they remain the only two live-action adaptations of “Peacock King” to this day. I hope Netflix will invest in an animated or live-action version.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Film Review: Nostalgia for Hong Kong Cinema 1990 “Peacock King” and “Saga of the Phoenix”