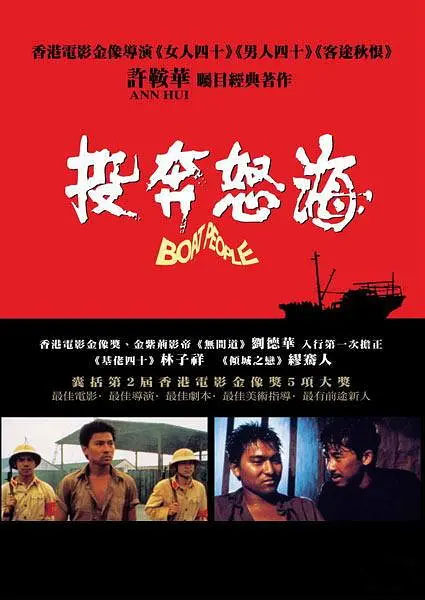

Film Name: 投奔怒海 / Boat People

Ann Hui’s 1982 film “Boat People” is a movie that sparked numerous discussions. Rumored to have been named by Jin Yong, it featured his dream lover Xia Meng as producer. Chow Yun-fat turned down the role for the Taiwanese market, leading to Andy Lau’s casting—his film debut. During production, Lau received guidance and encouragement from lead actor Sam Hui, which propelled him into the music industry. Other points of interest include filming in Hainan and the participation of mainland Chinese actors.

Yet once you watch this film, such gossip fades away. The movie possesses such compelling power that it effortlessly overshadows trivial rumors.

“Boat People” follows Japanese journalist Akutagawa (Lam Ka-shing), invited back to newly unified Vietnam by the government to document its reconstruction efforts after his previous assignment covering the revolution three years prior. In the “New Economic Zone,” Akutagawa witnesses staged “happy scenes” with children arranged for filming. This starkly contrasts with the reality he discovers when, filming alone without an escort, he encounters the life of 14-year-old Qin Niang and her family. Only then does he truly grasp the tragic plight of ordinary Vietnamese civilians under a harsh political environment.

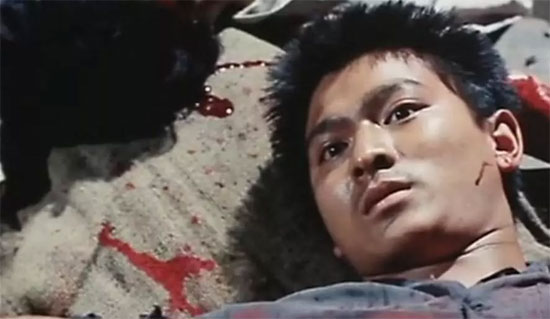

The film also weaves in a subplot: Zu Ming (Andy Lau), a former interpreter for the U.S. military, raises funds to flee the country. After enduring numerous hardships, he and his companions are caught in a government military barrage on their escape boat, with no survivors.

Though “Boat People” depicts Vietnam, its vivid red hue brims with metaphor. Through Akutagawa’s lens emerge characters like the Chinese “Madam” running a bar, Koto-chan’s mother forced into prostitution by poverty, and the bureaucratic female cadre from the Cultural Bureau. Among them, a Vietnamese Communist Party cadre educated in France who participated in the revolution utters the line, “The Vietnamese revolution succeeded, but my own revolution failed,” revealing the predicament of idealistic revolutionaries at the time.

This film grossed over HK$15 million at the Hong Kong box office, making it Ann Hui’s most commercially successful work. Considering the backdrop of the Sino-British negotiations in the 1980s, such box office success was predictable, tapping into the deep-seated “anti-communist” anxieties of many Hong Kongers.

Consequently, many critiques of the film were politically charged, despite the director’s denial that it was a political work, insisting instead it was a film about humanity.

Regardless of the director’s intent in making this statement, the most profound impact of “Boat People” lies not in its realistic portrayal of oppression under totalitarianism, but in the glimmer of humanity shining through the darkness.

Akutagawa and Koto-musume

Human nature is a complex concept, broadly encompassing both animalistic and divine elements. The closer one gets to survival instincts, the more animalistic the traits become; the nearer to morality, the more divine the aspects.

Under extreme conditions, universal human values vanish. The bar owner, “Madam,” sleeps with officials to make ends meet, yet uses the money to fund her lover (Zuming)’s escape. The two huddled together in the darkness, vowing to open a bar in America. To support her three children, Koto’s mother became a prostitute. Koto and her younger brother A-Le would cheerfully run to the execution grounds whenever they heard the firing squad’s shots, hoping to find a gold tooth in the dead man’s mouth or strip off a piece of old clothing to sell.

Death, the heaviest word in human existence, became a source of delight in the children’s eyes. Before Akutagawa, who followed them, they casually struck poses beside corpses. Lively children leaped and cheered beside bodies where bloodstains hadn’t yet dried. This stark contrast profoundly shocked Akutagawa. Scenes of “officials rounding up people at night” played out constantly. Those dragged off to dig mines risked being blown to pieces at any moment. One second, A-Le was laughing; the next, he was killed by a grenade he’d picked up. As the New Economic Zone captain told Zu Ming: Here, human life is worthless.

A-Le, who found the grenade

Yet human nature is also magnificent and resilient.

The “Madam” behind the bar, who had witnessed countless upheavals and the coldness of the world, had resigned herself to her fate. But she implored Akutagawa to tell Zu Ming not to accept his lot, to escape at all costs; When treating Zuoming’s inflamed, infected leg, Akutagawa discovered he’d hidden his saved gold coins within the wound. The coins were enough for Zuoming to escape alone, yet he kept saving, hoping to take the “Madam” with him. Akutagawa sold his most treasured camera and risked his own life to help Qin Niang and her brother escape.

Before the relentless wheels of history, every individual is as insignificant as dust—easily crushed and rendered invisible. Yet they are not insignificant. Great humanity burns itself on the path of redemption, illuminating others.

Just as Akutagawa did, using the fiery flames consuming him to illuminate the path ahead for the sister and brother.

When filming this movie, Ann Hui was not yet 35 years old, yet she already displayed the aura of a master, employing mature and restrained cinematography.

The film opens after North Vietnam unified South Vietnam, with columns of tanks rolling through the streets. Akutagawa is among the crowd, taking photographs. The camera pans to reveal soldiers atop the tanks, onlookers lining the streets, and people waving from upper floors. Returning to a medium shot, the military vehicles recede into the distance. Akutagawa, absorbed in his photography, notices a disabled child with a crutch. He follows the child into an alleyway to capture his silhouette, only to be startled by cheers: another convoy of tanks and military vehicles approaches.

The Welcoming Procession at the Film’s Opening

Amid the rumble of military vehicles and the roar of cheers lining the streets, the film’s title and production credits appear against a black backdrop—a design both ingenious and powerful.

Ann Hui spares no color: the red flags fluttering from buildings along the streets, the bloodstains on corpses, the fresh blood gushing from wounds, the crimson cloth draped over bodies—all flash with startling, jarring hues.

The glaring scars of the Vietnamese Communist Party member educated in France, the unclosed eyes of Zu Ming after being shot dead, and the raging flames engulfing Akutagawa create a stark contrast to the earlier scenes of children beaming bright smiles during Akutagawa’s staged performance and the serene pastoral landscapes. The softer, more comfortable green of the pre-designed “New Economic Zone” and the pleasant lives of its people and children stood in stark contrast to the jarring, oppressive scenes Akutagawa witnessed when alone. The orphanage children yearning for an adult’s embrace, the grimy alleyways, the Qin family’s shabby home with barely any furniture, the chaotic vegetable market, the frantic chaos of forced conscription, the corpses at the execution ground—all these scenes draw us, the viewers, alongside Akutagawa. Like in a dream, we gain our own perspective and bear witness to these realities.

The Unclosed Eyes of Zu Ming

Yet Ann Hui’s lens remains restrained and compassionate. When young Ah Lok is killed by a grenade he found, we never see the child’s mangled remains. A deafening explosion cuts to his sister Qin Niang’s anguished cries, followed by a shot of her shaking his body—yet the camera stays on her, never revealing the corpse. A long shot shows a man running with a red flag (though this shot feels slightly contrived). Close-up: The body is covered with the red flag, revealing only a pair of small, bloodstained feet.

Similar restraint is seen when Qin Niang’s mother commits suicide after being exposed for prostitution. Holding her second younger brother, Jie Chuan immediately covers his eyes, and the camera cuts to the mother’s burial.

These compassionate shots resemble human eyes averting their gaze from sorrowful scenes, unable to bear witness.

Director Ann Hui’s mastery shines even more vividly in depicting everyday reality. At the market, Qin Niang haggles over a few cents with a sugarcane vendor, only for their agreement to be shattered when soldiers arrive to conscript laborers. The haggling vendors, who’d fought over pennies moments before, now abandoned their baskets and crates, scattering in panic at the sight of “officials rounding up people at night.”

By the sea, Qin Niang bargained with the fishmonger for a fish, pulling Akutagawa along as if leaving to drive down the price. She bought the fish, imagining how delighted A-Le would be. Yet A-Le was killed by a bomb, never to see that fish. Akutagawa photographed Koto holding the fish, only to turn and see A-Le clutching a grenade.

Amidst such oppressive details, joy felt like a luxury—fragile and fleeting. One moment of happiness was swiftly followed by the crushing weight of its cost.

07

In the mature phase of “Summer Snow,” Ann Hui’s mastery of life’s minutiae becomes even more evident: At the fish stall in the market, Ah Eo gazes intently for a long while. The vendor deftly selects one, weighing it at one hundred and fifty dollars. Ah Eo loudly refuses, “Fifty.” The vendor retorts, “Fifty is the price for dead fish.” Ah Eo stands waiting for the fish to die, but it doesn’t. When the vendor isn’t looking, she slaps it to death. Then, without flinching, she declares, “It’s dead.”

In the kitchen, Ah Eo cuts the fish into portions, placing one back in the refrigerator before taking it out again.

Hesitation is the norm in a life of scarcity.

This normality is most familiar to every homemaker who worries about household expenses. These details, unearthed by the female director and brought to the screen, deliver a painful blow to the audience watching.

We may not have lived through such extreme times or experienced utter darkness, but the confusion about life and the anxiety about the future are universal. Of course, no film is perfect, and “Boat People” is no exception. A script written purely from imagination inevitably carries some flaws.

For instance, when Andy Lau’s character, Zu Ming, faces machine-gun fire during the escape, he crawls forward. Yet the next shot shows him suddenly leaping into the sea to be shot dead. It’s hard to imagine why someone crawling would abruptly jump up—the transition feels abrupt, lacking both continuity and psychological revelation.

Akutagawa’s death also lacks logical coherence. From basic chemistry: diesel fuel’s flash point (the lowest temperature at which its vapor-air mixture ignites), molecular structure, and low volatility mean it wouldn’t explode and engulf him in flames from a single gunshot. Moreover, the patrolling officer had already checked Akutagawa’s pass, so further pursuit seemed unlikely. Moreover, the Koto sisters and brother boarded the ship without diesel fuel, rendering Akutagawa’s barrel unnecessary.

The director crafted Akutagawa’s death as the most heroic sacrifice—immolating himself to illuminate the ship’s survivors. While profoundly impactful, this conclusion now feels contrived and overly contrived.

Perhaps even the director of that era couldn’t envision the future for the sister and brother. Though light lay ahead, at just fourteen years old—having witnessed her brother blown to pieces, her mother die before her eyes, and her savior (and first love) burn to death in her sight—what path could her life possibly take? Who could guarantee their boat wouldn’t meet the same fate as Zu Ming’s vessel?

Everything remained unknown.

Perhaps now, that era has passed, and those political movements have become history.

Hainan, where this film was shot, has since become an international tourist island. I wonder how director Ann Hui views this film from back then today.

My personal wish for the ending is that Akutagawa also left Vietnam, opening a photography exhibition showcasing his photos of the country.

As for him and Qin Niang, I always hope that kind-hearted people will have a good outcome.

If everyone were to illuminate their own spiritual clarity and follow their conscience, extreme environments would never recur.

The light of humanity may not always triumph over darkness, but it cannot be extinguished by it.

Such humanity may not be grand, but it is certainly noble.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Boat People 1982 Film Review: Humanity may not be great, but it must be noble.