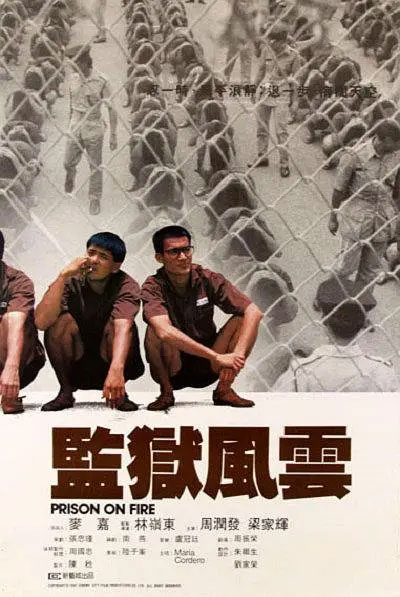

Film Name: 监狱风云 / Prison on Fire / 監獄風雲

This prison film, shot in 1987, is the pioneering work of Chinese-language prison cinema and an internationally acclaimed masterpiece of the genre.

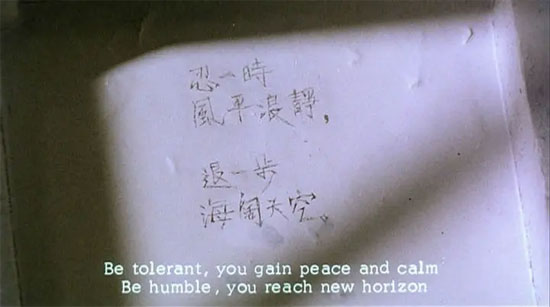

I remember watching Prison on Fire for the first time when I was very young. After watching it, I only remembered one lesson: one must endure. By enduring for a moment, the storm subsides; by stepping back, the sky opens wide—just as Zheng Ge wrote on the prison bench.

Of course, if viewed purely as a film teaching patience, this movie clearly falls short. After all, Zheng Ge ultimately couldn’t hold back, violently biting off the prison warden’s ear. Moreover, the film seems to deliberately emphasize this scene—the moment Zheng Ge spits out the blood-soaked ear, he achieves liberation.

With the upcoming Hong Kong Film Festival approaching, I revisited this film as its promotional ambassador. After watching it again, my understanding gained new dimensions.

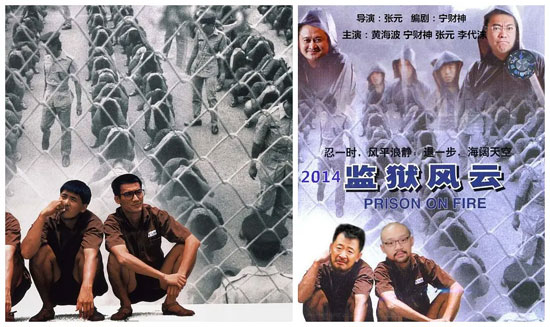

First, this is arguably the first Chinese-language prison film, released in 1987 and considered the pioneer of the genre. How iconic is this film? Recently, netizens mocked a prison blockbuster featuring a cast of drug-addicted celebrities, whose parody poster directly mimicked Prison on Fire. Notably, Anthony Cheung, who played the murderous hero in Prison on Fire, was later reported by vigilant citizens for drug use. Ah, digressing—back to the main point.

Directed by the renowned Ringo Lam, the film showcases his pioneering spirit and commendable courage. Criticizing the prison system and exposing society’s dark underbelly was never a popular move, even during Hong Kong cinema’s golden age. The film exposed many sharp social issues. Take Tony Leung Ka-fai’s character, Ah Yiu, for instance. He was sentenced to three years for manslaughter after confronting street thugs who refused to pay for goods and then assaulted him. The film also depicted corrupt prison staff who acted brutally, bullying the weak and trampling on prisoners’ dignity. The prison warden acts like a god within the walls, framing whoever he wants, exploiting whoever suits his purposes, and colluding with gang bosses. He understands that if prisoners unite, it weakens his control over rival factions. Thus, he goes to great lengths to stir up trouble, inciting gang leaders and manufacturing conflicts. This demonstrates that when those who should embody justice begin committing evil, no one can stop them. Perhaps it was precisely this insight into this inescapable pattern that drove the long-suffering Zheng to vent his fury through extreme means in the end—scenes that remain profoundly chilling even today.

Second, this film is truly “wicked to the core.” For starters, three of Hong Kong cinema’s Four Villains appear in it: Ho Ka-kui, Cheng Kwai-on, and Wong Kwong-leung. As far as I know, this very film cemented their status as iconic villains in Hong Kong cinema.

He Jiagu as Big Mimi

Cheng Kui’an as Big Fool

Huang Guangliang as Foolish Biao

Additionally, Zhang Yaoyang, who plays the prison warden, has spent nearly his entire acting career portraying villains.

Prison Warden

Plus gangster specialist Brother B, played by Ng Chi-hung

Brother B, Ng Chi-hung

With so many powerhouse “villains” crammed into the marginalized setting of a prison, how could it not be compelling?

Also worth noting is the chivalrous spirit of this film. In truth, Hong Kong gangster films of the last century all carried a touch of this chivalry—whether in John Woo or Andrew Lau’s works, whether it was Little Horse or South Chen. This reminds me of Kong Erdou’s exposition on the classical rogue in Northeast China’s underworld. They were all 80s-era hoodlums and thugs, loyal to their gangs, adhering to principles and boundaries, and taking responsibility for their brothers. They cared little for fame or fortune, but valued loyalty above all. The gang conflicts in the film stem from bosses fighting for their brothers’ interests. Even when the scheming Big Mimi—played by Ho Ka-kui, dubbed the “Chief of the Four Villains” in Hong Kong’s entertainment industry— the prison warden threatened him to identify the leader of a hunger strike protesting cafeteria price hikes, Da Mi insisted on first explaining the situation to his brothers. He refused to go back on his word and betray their trust. It is precisely this chivalrous spirit that gives Chinese-language gangster films an irresistible charm.

The music is another highlight of this film. Composed by renowned musician Alan Tam, the theme song “The Light of Friendship” plays twice throughout the film. Anyone who has heard it will find this piece perfectly captures the film’s essence. The lyrics were penned by the film’s screenwriter, Nan Yan, and delivered with Maria’s signature husky yet powerful vocals, making it deeply moving. The insert song “Chong Man Xi Wang” is also performed by Maria Kei, and these two tracks cemented her status in Hong Kong’s music scene.

Finally, I’d like to say that despite the film’s seemingly heavy negativity on the surface, it still carries profound educational value. After witnessing the despair within the prison walls, one is struck by a profound sense of helplessness—the prison system drives the kind and upright Ah Yiu to attempt suicide by cutting open his stomach with glass, and forces the smooth-talking Zheng Ge to resort to the most extreme measures to solve problems. This experience leaves you silently warning yourself: Never break the law. Never end up in prison.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Prison on Fire 1987 Film Review: This is the real prison drama.