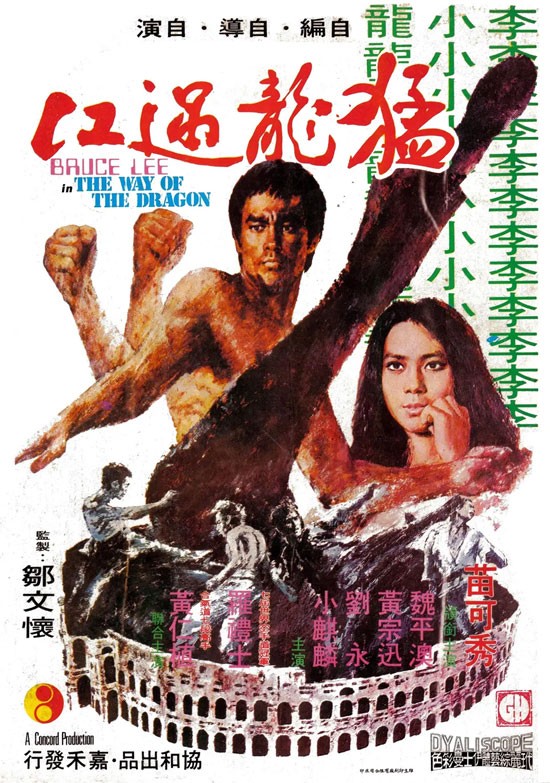

Film Name: 猛龙过江 / The Way of the Dragon / Fury of the Dragon / Mang lung goh kong / Return of the Dragon / Revenge of the Dragon / 猛龍過江

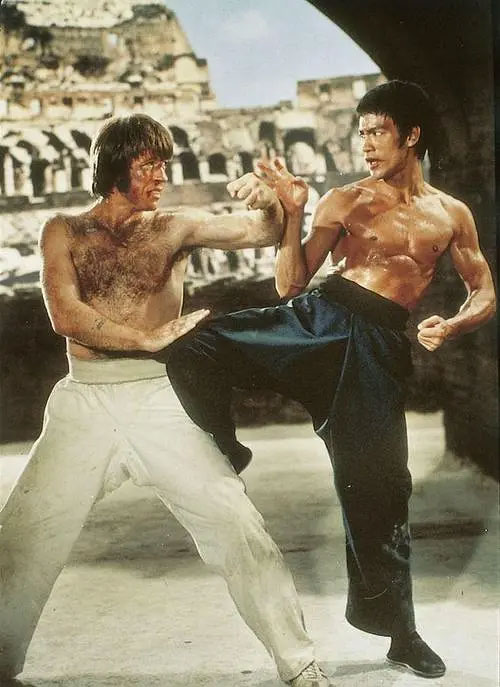

The Way of the Dragon is an action film written, directed, and starring Bruce Lee. The classic scene of the film is undoubtedly the final duel. The final showdown takes place at the Colosseum, a historical arena where gladiators battled animals. This venue served as entertainment for spectators and nobility, who treated gladiators like beasts—locking them in cages to fight tigers and lions. In the film’s final showdown, however, a cat watches the human combat. This scene creates a striking contrast within the narrative. Bruce Lee’s creation of this moment and his deliberate choice of the Colosseum as the location for the duel were clearly intentional.

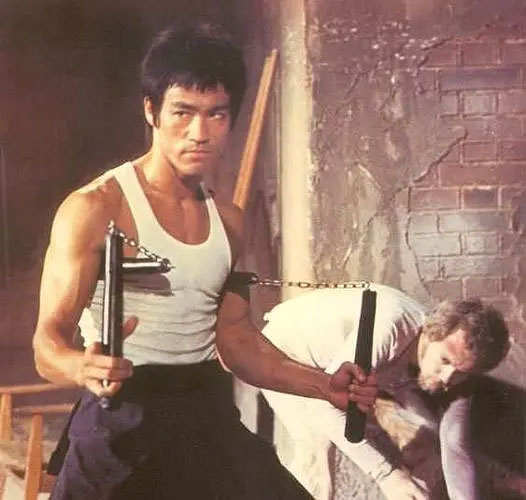

In the final duel, Bruce Lee’s character, Tang Lung (incidentally, Lee’s script notes explain the name: “Tang” reflects how Chinese people historically referred to themselves as “Tang people,” while ‘Lung’ symbolizes the dragon, China’s unique mythical beast), confronts Bruce Lee’s character. Their clash embodies the “mutual admiration between masters”—a clash not of competing interests, but a clash of dignity, infused with the spirit of “never missing the chance to face a true opponent.” Moreover, this duel reflects the essence of martial arts: the pursuit of perfection and the respect for one’s opponent. mutual respect.” Their clash isn’t about conflicting interests but a contest of dignity, carrying the implication that “when you meet a true master, you can’t pass up the chance.” Moreover, this fight partially embodies Bruce Lee’s own philosophy of combat. Bruce Lee believed true combat transcends martial arts styles and victory itself; its essence lies in the process. While winning matters, it remains merely an outcome. What truly counts is giving one’s all in the fight—a genuine expression of self while honoring the opponent. Thus, he saw combat as a form of communication, albeit a brutal one. Combat brings people closer, yet ironically, it is also merciless. In the finale, Lo Li-shih’s character gradually loses ground in the duel until his arms and knees are broken. Tang Lung signals that the fight need not continue, as his opponent is now crippled. Yet Lo Li-shih still tries to rise, wanting to keep fighting Tang Lung. In truth, he wasn’t seeking combat but death. Having been crippled, survival felt like a disgrace. With a final roar, he charged at Tang Long, begging to be killed. Tang Long, with no other choice, granted his wish. The shot after the kill is a close-up of Tang Long’s face. It shows a look of resignation, perhaps even regret at losing a worthy opponent.

Finally, Tang Long draped his own clothes over the fallen man. This gesture signified that humans should not die like animals, while also showing a measure of respect for his opponent. In this film, Bruce Lee directly articulated his understanding of martial arts combat. Simultaneously, the film expressed his own resignation in the face of reality. The repeated appearance of firearms in the film reflects Bruce Lee’s conflicted view of reality: martial arts would inevitably decline in an era dominated by modern weaponry. For its time, this film’s fight sequences and thematic depth were utterly ahead of its era. Bruce Lee’s thinking itself transcended the limitations of his time. In that era, the world had never seen an action star like Bruce Lee. His films not only influenced future generations but will forever be etched into cinematic history. The action films we watch today essentially stem from Bruce Lee. His personal charm lay in embodying the ancient, scholarly qualities of a martial artist. Yet it is deeply regrettable that he died so young, leaving Jeet Kune Do unfinished. Bruce Lee once stated that naming it “Jeet Kune Do” was a decision he regretted. Jeet Kune Do is not a martial arts style, merely a designation. It is a combat system synthesizing the strengths of various schools, designed for real combat and self-defense.

“There is no strongest martial art, only the strongest martial artist.” Martial arts cultivation lies in the individual, not in the type or style of martial art.

“To take the impossible as possible, the infinite as finite”—this phrase itself carries profound philosophical meaning. It implies that any interpretation of this statement is valid. The crucial point lies in whether you can draw deeper insights from what you learn and make it your own. This was precisely what Bruce Lee consistently advocated: do not limit your thinking; empty your mind. The Jeet Kune Do he created has no rigid rules. When facing an opponent, one adapts to the opponent’s changes—this is the fundamental theory of Jeet Kune Do. To be precise, Jeet Kune Do is not a martial art per se, but rather a philosophical system that inspires you to learn from the strengths of various schools and master them. Therefore, Jeet Kune Do has no fixed forms to practice and is not bound by rules, just like water.

Though Bruce Lee is known worldwide as a martial artist, he was fundamentally a philosopher throughout his life. Had he not passed away, he would likely have become a filmmaker with the stature of a philosopher.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » The Way of the Dragon 1972 Film Review: Colosseum Duel: Bruce Lee’s Interpretation of Combat