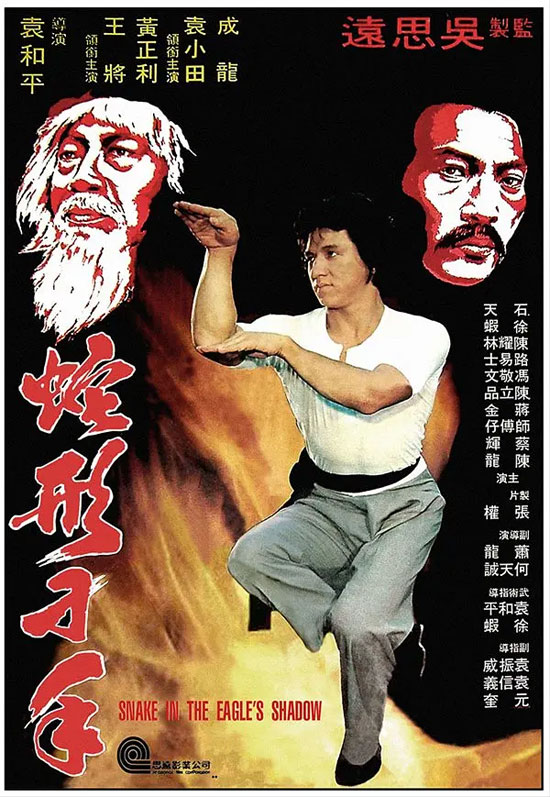

Film Name: 蛇形刁手 / Snake-shaped hand / Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow

This wasn’t Jackie Chan’s debut film, but it was the one that made him famous. There’s been a lot of criticism about it, and I’ll share my own thoughts… If Jackie Chan pioneered the comedic kung fu film genre, it was likely out of necessity. First, he couldn’t replicate Bruce Lee’s charisma or philosophy. Second, his own image limited his heroic appeal—he could only play the underdog. Back then, he wasn’t the leading man he is today… In terms of cinematic language, Yuen Woo-ping remains better suited as a martial arts choreographer. He expands the imaginative scope within confined spaces and combat sequences, blending acrobatics with the actors’ inherent physicality to prevent prolonged fights from becoming tedious. One could say Jackie Chan, Yuen Woo-ping, and the tradition of Peking Opera martial performers share deep roots—particularly in scene composition and pacing, which are meticulously structured and rhythmically precise, bearing the distinct flavor of Peking Opera martial arts. This sets them apart from previous kung fu directors… The issue lies in his visual language, which feels relatively monotonous. While he varies shots and framing, it often feels contrived. Beyond dialogue sequences that follow established conventions, his use of out-of-focus transitions during scene changes feels jarring to the audience. In character confrontations, to showcase the actors’ genuine skills, he extensively employs long takes. Yet, the transition between shots abandons montage editing in favor of direct zooms—a technique long discarded by Hollywood for its loss of realism and potential to disorient viewers. Understandably, coming from a martial arts background, Yuen is eager to showcase the kung fu, but this approach struggles to sustain audience engagement over time… In terms of narrative structure, films from this era embraced subversive themes. He sought to kill his father, distinguishing himself from all previous action films, especially those of Bruce Lee. Without familial or national vendettas, the fights became meaningless—everyone was just hot-blooded and aggressive. The masters themselves become caricatures, reduced to comedic tropes. What remains is sentimentality rather than reverence—a shift catering to the mindset of Hong Kong’s post-war youth, the first generation raised on Western education who challenged traditional morality. The narrative’s greatest flaw lies in its formulaic repetition and weak conclusions, a common pitfall in Jackie Chan’s films from this era… The musical score carries a distinctly postmodern feel, transforming everything into a game with its playful, arcade-like tunes that engage the audience. Occasional classical interludes skillfully heighten the atmosphere, though their overuse feels crude, leaving viewers weary and sensing artificiality… Ideologically, I personally believe this film holds unique significance. In 1978, the Cultural Revolution ended on the mainland, the Deng regime took power, and reforms were initiated. Meanwhile, Hong Kong, under British rule, experienced rapid economic growth, ushering in a wave of materialism. It’s no longer about Snake Style Kung Fu or Eagle Claw Kung Fu. The ultimate victor is Jackie Chan’s Snake Style Kung Fu integrated with Cat Claws. This represents the prevailing mindset of Hong Kong’s civil society: materialism and utilitarianism. The saying “A cat that catches mice is a good cat, regardless of its color”—a quote from a leader—is particularly thought-provoking. Further elaboration: the snake symbolizes the dragon. Jackie Chan’s mastery of snake fist can be interpreted as Hong Kong’s preservation of mainland cultural heritage as an “other.” His spontaneous creation of cat claws represents innovation rooted in tradition while also emulating the West. The eagle claw practitioners—whether dressed as Manchus or missionaries—embody traditional feudal China and Western culture respectively, both ultimately defeated by cat claws. Thus, the core of Hong Kong culture also carries a bias against both the West and feudalism. They believed the mainland’s snake fist, as depicted in the film, was on the verge of extinction. Having learned snake fist and then invented eagle claw, they claimed orthodoxy. They had lost hope in snake fist yet could not accept either the feudal or Western eagle claw. Thus, cat claw became their innovation and adaptation… Of course, this interpretation risks over-explanation, yet it offers a pathway to understanding… From a psychoanalytic perspective, Jackie Chan’s portrayal of the neighborhood kid embodies vulnerability. When faced with existential threats of emasculation, these characters invariably learn peerless martial arts from eccentric masters, ultimately reclaiming their agency. This narrative has become a formulaic trope. Moreover, Jackie Chan’s films are essentially male-centric. He rarely casts women, and his protagonists are often boys who seem devoid of libido. This asceticism may be an homage to Bruce Lee, or perhaps Jackie simply found it difficult to cast female co-stars—constrained by his own image, he feared compromising his heroic status. In his relationship with the master, Jackie always seeks to surpass him—a manifestation of the Oedipal complex. He learns the master’s martial arts but ultimately innovates. When confronted with the father-killing dilemma, the film resolves it by having the master depart, fading into the crowd. This provides a satisfying conclusion to the aforementioned psychoanalytic theory…

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Snake-shaped hand 1978 Film Review: The Triumph of Utilitarianism