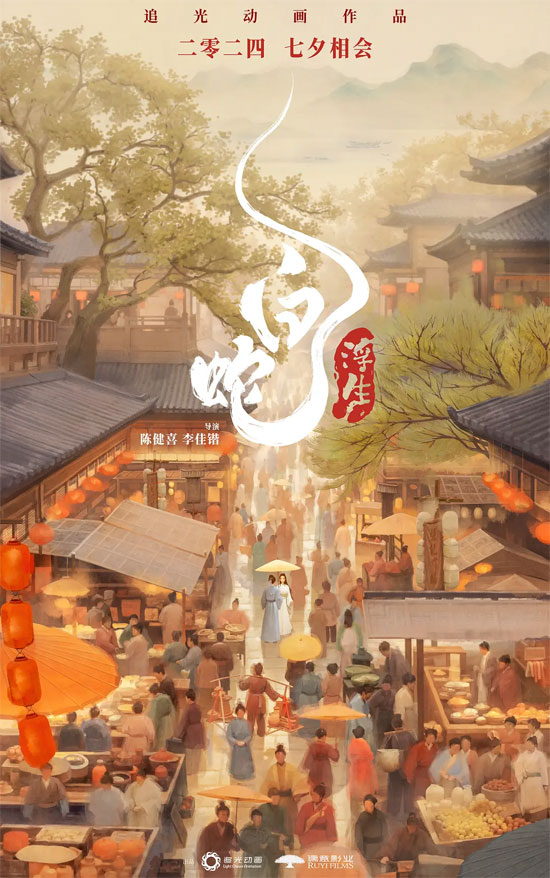

Film Name: 白蛇:浮生 / White Snake: Afloat

The “White Snake” trilogy by Zui Guang Animation has finally concluded. Compared to the stunningly crafted prequel “White Snake,” which explored the past lives of Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian, and the wildly imaginative “Green Snake,” which transported the Green Snake into a cyberpunk world, this final installment, “White Snake: Afloat,” presents audiences with a narrative that feels constrained by a certain “formulaic” mindset, all while cloaked in its beautiful visual style.

The White Snake saga has concluded, and with it, the creative vision and inspiration behind it. The “New Mythology” ultimately returns to the “Old Story.”

In truth, once the White Snake tale introduced the “origin” of their past lives, the encounter between Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian in their present existence was no longer predestined—it was rewritten. When Lady Bai’s gratitude is directed not toward Xu Xian himself, but toward his past life incarnation Xu Xuan, the relationship between Lady Bai and Xu Xian transforms from pure to contrived. When we construct what we deem a plausible prequel for a folk tale, perhaps the only thing that remains plausible is the newly fabricated prequel itself. The emotions, logic, and motivations of the characters in the original narrative have already, silently, become less plausible.

Are Xu Xuan and Xu Xian truly the same person? Can a reincarnated soul and its past incarnation be considered one and the same? Would a woman (Bai Niangzi) who loved a man who sacrificed himself for her (Xu Xuan) unhesitatingly love that man’s reincarnation (Xu Xian)? Regardless of any soul connection, bloodline ties, physical resemblance, or shared temperament between Xu Xuan and Xu Xian, aren’t they still two distinct, flesh-and-blood individuals living in different eras? Bai She’s repeated insistence of “I remember” transforms her love interest from a unique “original copy” into a “duplicate” capable of endless rebirth.

The film’s title, “Floating Life,” appears profoundly philosophical but ultimately fails to capture the essence of human existence. Two hours is simply insufficient to explore the theme of “floating life.” Though the film diligently portrays the tender moments of mutual support between Bai and Xu Xian, these glimpses fall short of building a profound understanding of their cross-species love. Consequently, their final sacrifice for one another fails to move the audience.

Moreover, the film specifically depicts traditional festivals from the Cold Food Festival, Dragon Boat Festival, Mid-Autumn Festival, Double Ninth Festival to the Lantern Festival, as if Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian had only spent a year together before the story concluded. Earlier, the White Snake vowed to stay with Xu Xian for a hundred years. Yet her arrival only granted him a single year of life—truly a fleeting existence, like “a passing shadow.” Was she here to repay a debt of gratitude, or to exact revenge? To label such a year as the theme of “fleeting life” is like tossing a single bean into a massive wok for frying—utterly unrealistic.

In classical Chinese fiction, both the White Snake and Green Snake were portrayed as malevolent entities sent to harm Xu Xian, while Fahai alone represented the righteous force vanquishing demons. Thus, his repeated assertion that “demons are born to harm humans” holds absolute validity. It’s only through later adaptations that this tale has been reimagined to carry themes of human-demon romance, gradually humanizing the demons and demonizing Fahai, transforming it into a story of love transcending social barriers and breaking traditional shackles.

In contemporary works like “White Snake: Afloat,” we still encounter traces of this tension from the transition between ancient novels and modern adaptations. For instance, when Xiaoqing steals government silver to fund Xu Xian’s pharmacy, this act would be utterly immoral and lawless without the context that the silver was unjustly acquired. Yet in the film, Xiaoqing faces no consequences for this theft.

A pivotal scene in this work is Xu Xian’s first revelation that his wife is a snake demon. Prior to this, no matter how blissful or deeply connected their life together seemed, it was like a moon reflected in water—existing solely for the moment it would shatter. Only when that illusion breaks do their true human charms emerge. The end of their false relationship marks the beginning of their genuine understanding and spiritual recognition of each other.

On a stormy night, Xu Xian learns the truth through Fahai’s words. Yet without hesitation, he immediately pleads with Fahai to spare the White Snake. I feel this scene completely fails to convey the emotional tension it should. Imagine discovering your beloved, the one you share your bed with, is a snake demon—could you truly accept it? Or accept it so swiftly? Surely there would be some internal struggle? First comes shock and disbelief, then a sense of betrayal and victimhood. Only gradually does one recall the beloved’s kindness, thoughtfulness, and support, fostering an emotion transcending species—concluding that even a demon is acceptable.

This crucial process is entirely omitted from the film, representing a massive simplification. And what it simplifies is precisely the most authentic human interpretation of “fleeting existence.”

Another disappointment in the film lies in its inconsistent portrayal of the jeweled hairpin. From the very beginning, the film focuses on this crucial token and prop with close-ups. Bai Suzhen carefully buries it underground, only to later retrieve it, symbolizing her sealing and restoration of her demonic identity and powers—though her demonic abilities were never truly sealed as promised. The monk from Baoqing Temple specifically highlights the hairpin, seemingly foreshadowing its pivotal role. Yet despite all this setup, the hairpin is never ultimately used, leaving its inherent power and emotional weight entirely unreleased.

Of course, the film’s strengths are undeniable. Its exquisitely rendered Chinese-style visuals and rich traditional cultural elements deliver immense visual pleasure. Particularly intriguing is the incorporation of numerous traditional Chinese medicine motifs—bronze mannequins, acupuncture, medicine cabinets, herbal pots—subtly conveying the essence of Chinese medical culture. The film’s thoughtful, evocative details are also uncommon in domestic animation. For instance, the fusion of two red candles, or the use of a willow tree by the gate to symbolize love, evokes the poetic line: “The moon rises above the willow tips, a rendezvous after dusk.” Moreover, the supporting characters shine brilliantly. Whether it’s Xu Xian’s brother-in-law, the two crane-like celestial children, or the lion-dog hybrid golden-haired Hou, each leaves a lasting impression.

Another widely praised highlight is the depiction of Baoqingfang. As one of the most original elements in the entire “White Snake” series, Baoqingfang adds an air of mysticism and showcases the animation’s charm. Whenever scenes unfold at Baoqingfang—whether within its enigmatic interior spaces or during its lively, whimsical opera performances—they captivate audiences most profoundly. Much like the Minions breaking free from Despicable Me to star in their own films, the White Snake saga’s narrative evolution may no longer center solely on Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian, but rather shift toward the world of Baoqingfang itself.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » White Snake: Afloat 2024 Animation Film Review: “New Mythology” Returns to “Old Stories”