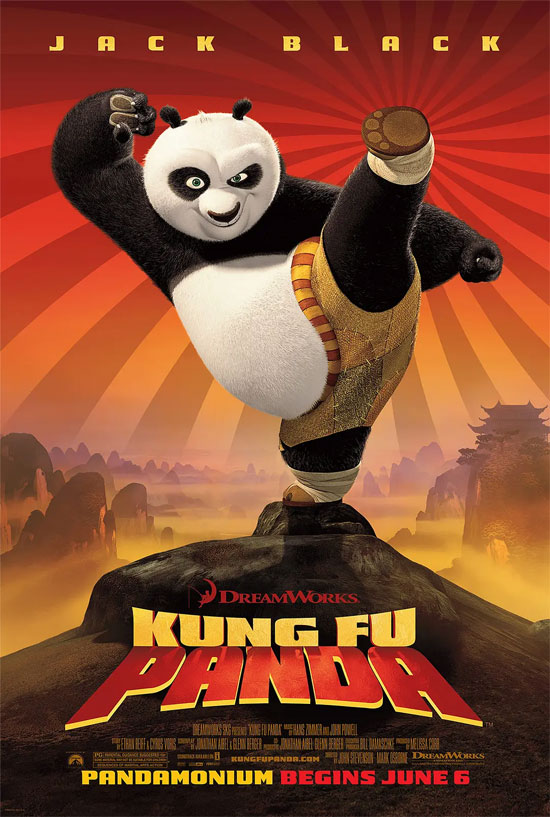

Film Name: 功夫熊猫 / Kung Fu Panda

Martial arts culture is the only popular culture China has contributed to the world. For an ancient civilization, this is a kind of sorrow, yet for a China that was suppressed by Western modern civilization for over a century, it cannot be considered anything but a form of luck. We produced many classic martial arts novels and films in the last century, which greatly benefited the popularization and flourishing of martial arts culture. However, while many believe “Storm Rider” represents Americans promoting Chinese martial arts culture, I see it precisely the opposite. Only through our own hands can we truly elevate our native culture; in others’ hands, it merely becomes a vehicle for other civilizations to flourish.

“Storm Rider” vividly illustrates how Chinese culture, repackaged with a Western core, transforms into a cultural product that achieves global popularity and box office success.

What constitutes the Chinese packaging? The film’s Chinese-style backdrop, architecture, music, five martial arts styles, dragon totems, firecrackers, noodles, and buns—and of course, the very premise of featuring a panda as the protagonist and kung fu as the selling point. What defines the Western core? The entirely Western values embodied in the hero’s birth, growth, and coronation within the narrative.

We observe that Po the panda begins as an ordinary character. Though he unexpectedly becomes a candidate for Dragon Warrior, his selection occurs through an electoral ceremony. In other words, while his destiny as a hero is predetermined, his emergence must demonstrate equality through established rules. This embodies a classic Western paradox: the belief that anyone can become a hero, yet heroes are often destined from birth. The 80th Academy Award-winning animated feature “Ratatouille” contains a similar element: while the story’s core message is “anyone can cook,” we observe that the mouse with extraordinary culinary skills is not just any member of the rat family, but the one most gifted with taste. So, is his success due to his innate talent, or to the spirit of universal culinary potential the film champions? Classical Chinese martial arts literature lacks this emphasis on equality and fairness. In China, not everyone can become a hero; lineage often predetermines one’s destiny from the outset. Had Xu Liang and Bai Yunrui not been the sons of Xu Qing and Bai Yutang—two of the Five Gallants—they would never have received martial arts training from renowned masters. This unspoken rule permeates “Three Heroes and Five Gallants” and many other ancient Chinese martial arts novels.

We also note that during Po the panda’s journey, the film’s most powerful character, Master Oogway, undergoes a death sequence—a classic Oedipal motif symbolizing “the abdication of the father figure.” After fulfilling his role as guide, Master Oogway vanishes, creating genuine space for the hero’s growth. In fact, similar narratives appear in many American animated films. For instance, in The Lion King, if Simba’s father had not died, Simba would never have transcended him to ascend the throne. Such a setup is rare in traditional Chinese stories, where the strongest figure is either the ultimate villain to be defeated or a reclusive sage whose realm transcends all others, rendering abdication unnecessary. Ultimately, this stems from the deeply ingrained hierarchical mindset within Chinese martial arts culture. The highest-ranking, most formidable characters are either targets of revolution or symbols of absolute power capable of commanding and controlling everything. In contrast, Western narratives hold that when a new powerhouse emerges, the old guard has no justification for clinging to their position indefinitely. Of course, many modern Chinese martial arts novels have gradually adopted this Oedipal dynamic, though this narrative of transcending patriarchal authority remains a classic paradigm rooted in Greek mythology.

Po’s hero coronation was achieved by defeating the crippled leopard. This binary opposition between pure righteousness and pure evil, along with the ultimately triumphant and highly responsible victory of the righteous side, embodies the essence of the American hero. However, this is absolutely not the essence of the Chinese hero. The essence of the Chinese hero lies in concepts such as benevolence, righteousness, loyalty, and filial piety. In other words, the people’s reverence and identification with Chinese heroes stems from their moral nobility, not from awe of overwhelming power as depicted in “Storm Rider.” The supremacy of raw power represents the most Western aspect of “Storm Rider.” The notion that a sense of responsibility to save the masses, commensurate with one’s abilities, constitutes a moral virtue is a Western concept. This diverges significantly from traditional Chinese moral values—for instance, Po’s defiance of his father’s will to pursue martial arts embodies a liberalism that starkly contradicts the Eastern filial piety of obeying parental commands. Yet, this liberal perspective is precisely what resonates with Chinese youth.

Indeed, the entire story brims with nuanced details revealing Western influences. Take Po’s father, for instance, whose relentless pursuit of commercial success drives him to expand his noodle business—even aiming to sell noodles at the grand Dragon Warrior selection ceremony. The scene where Master Oogway instructs Po beneath the peach tree also references a cultural allusion: Initially, Po’s mouth is stuffed full of peaches. But after Master Oogway enlightens his mind and departs, Po sits beneath the peach tree when suddenly a peach falls into his hand—symbolizing his sudden enlightenment and profound spiritual awakening, much like how Newton discovered the law of universal gravitation. Finally, Po emerges from a cloud of smoke wearing a wok on his head—a nod to the classic Warcraft game’s panda design. Moreover, the prison holding the crippled leopard shows no trace of Chinese elements—while China has stories of imprisoning people in caves, these caves typically extend horizontally into mountains rather than vertically underground. The prison in “Storm Rider” resembles the eighteen levels of hell.

In short, while “Storm Rider” undeniably showcases Chinese elements, these elements are merely a sugar coating wrapped around Western values.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Kung Fu Panda 2008 Animation Film Review: The Core of Western Culture