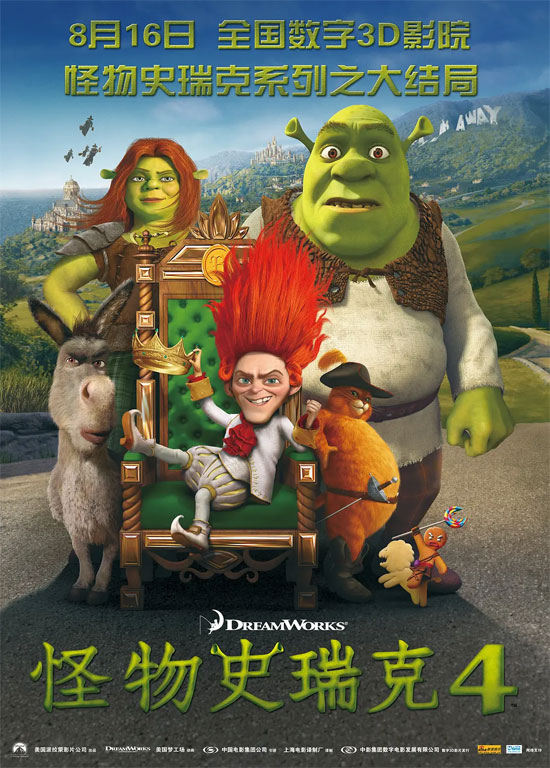

Film Name: 怪物史瑞克4 / Shrek Forever After / Shrek 4

Perhaps because I arrived two minutes late to the screening, I never felt fully immersed in the plot throughout the entire film. Instead, I remained detached, hovering on the periphery. Or maybe this inability to engage wasn’t my fault at all, but rather an inevitable consequence of the “Shrek” story reaching its fourth installment—a franchise that never should have had a second or third movie, let alone a fourth.

Shrek’s origin was steeped in subversion. One could say that overturning tradition and defying classics was the defining characteristic, the biggest selling point, and the greatest success of both the Shrek character and the first film in the series. He subverted the conventionally handsome appearance of animated protagonists. He subverted every civilized behavior in human life—like bathing, quietly passing gas, eating with graceful manners, and so on. He also subverted countless classics like Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and Pinocchio. This series of subversions endows Shrek with a unique value and grants the first film extraordinary appeal. After watching the movie, audiences delight in discussing this incredibly vivid, large-bodied character—ugly on the outside yet kind-hearted, uncouth in manner yet romantically inclined.

Perhaps buoyed by the first Shrek’s immense success, audiences eagerly anticipated what happened next to the Shrek couple, leading to the sequel. In this installment, the film naturally explores hypothetical narratives—using Shrek’s transformation into human form to illustrate that physical appearance matters little, while a loving heart is paramount. Ultimately, both protagonists revert to their monstrous forms. A key point here is that the director begins justifying Shrek’s monstrous appearance—deliberately portraying him as a monster to highlight his fiercer-than-human heart, creating a stark contrast. In the first film, he was born a monster, requiring no explanation or justification. We know groundbreaking works defy explanation—never spell out why they’re revolutionary, lest the magic vanishes. Shrek 2 uses explanatory language and bluntly obvious methods to restate lessons audiences already grasped and felt in Shrek 1. Isn’t this redundant?

For “Shrek 3,” audiences went to see it more out of habit than desire. People weren’t really curious about what new adventures the big guy had gotten himself into. Instead, they thought, “Oh, the big guy’s back? Might as well go see it.” Why the lack of curiosity? Because by the time of “Shrek 2,” this big guy had already become mundane. He’d been co-opted by ordinary, worldly life, no longer an otherworldly figure but reduced to a worldly one. In the first film, he transformed princesses into monsters—that marvelous sense of elevating an inherently worldly character to a transcendent realm. This magic not only vanished in the subsequent two installments but gradually transformed into: two transcendent beings living mundane lives, interacting with ordinary people, constantly influenced by them, and ultimately becoming fully immersed in the mundane world themselves. By Shrek 3, Shrek’s ethereal mystique had not only been stripped away but overlaid with classic hero tropes—a move tantamount to suicide for a character built on subverting tradition.

By “Shrek 4,” audiences sighed with relief that it was finally over—a feeling tinged with both conflict and lingering nostalgia. On one hand, they cherished the memory of that original, larger-than-life outsider; on the other, they couldn’t bear to watch him become increasingly ordinary. Indeed, Shrek’s gradual transformation into a Hollywood mainstream hero truly brought the series to its end, for it was no longer subverting others but subverting itself. The only somewhat notable subversion in this film was the Fat Cat character; the rest of the plot felt like a forced contrivance. For instance, Shrek is fundamentally a loner, yet “Shrek 4” insisted on introducing a whole host of monsters, forcing the green ogre into a racial identity. This is a colossal misstep, as it pointlessly subverts the core premise of the first film—the standout individuality of an “ugly monster with a kind heart.” The Shrek we need must be unconventional and unique, not generic and collective. The contrast between ugliness and kindness is starkly defined in Shrek’s individuality. How can you convey collective kindness amidst a horde of ugly creatures? It’s like Beauty and the Beast—there can only ever be one Beast, not multiple beasts.

Shrek’s path toward self-subversion was inevitable. Even the most distinctive character becomes ordinary when subjected to endless sequels; even the most groundbreaking plot can only subvert tradition once, not repeatedly. If Shrek 1 was a brilliant concept, then 2, 3, and 4 were merely successful commercial ventures. True subversion, once achieved, is sufficient.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Shrek Forever After 2010 Animation Film Review: Shrek, who has always been subverting others, has now subverted himself.