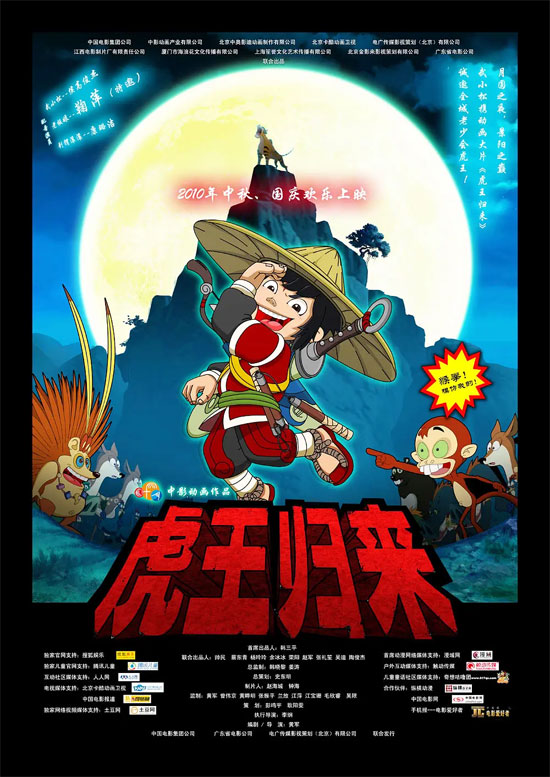

Film Name: 虎王归来 / Tiger Returns / Hu Wang Gui Lai

In recent years, as an audience member, I believe I’ve done my part to support domestic animation. My greatest effort has been making a conscious effort to watch newly released domestic animated films in theaters. Aside from Pleasant Goat, Tiger Returns attracted a relatively larger audience. Released during the Mid-Autumn Festival season, it typically drew parents bringing their children to watch. When the entire theater of children excitedly joined the little hedgehog in the film as referees, counting along, you realize it’s quite a moving sight.

We shouldn’t be overly self-deprecating about domestic animation. Before the film even premieres, irresponsible netizens on some movie rating sites give it irresponsibly low scores like 0 or 1 stars. This is wrong. Yet such reactions are sometimes understandable, as people are driven by emotion. Once we harbor biases against domestic animation, these feelings can lead us to make similar judgments.

We often treat our peers and familiar subjects with harshness and disdain, while approaching unfamiliar fields with awe and respect—a fascinating psychological phenomenon. This is precisely the case with Chinese animation. Many industry insiders, seeing Pleasant Goat achieve significant market success, feel a mix of envy and resentment. They go out of their way to criticize it, dismissing it as nothing special and pointing out every flaw. Yet when asked to create a film with comparable market impact, they all fall flat. And what about the audience? Don’t they also scrutinize domestic animation through tinted glasses, fueled by some inexplicable resentment? Every new release gets torn apart, as if criticizing it is the only way to prove their discernment and taste. Is Chinese animation truly all flaws and no merits? Has it only regressed, never progressed? Can belittling and abuse truly elevate Chinese animation? I don’t think so. What Chinese animation urgently needs now, besides its own hardware and software, is a supportive and tolerant environment—one that requires the collective effort of both animators and audiences to create.

Frankly, “Tiger Returns” exceeded my expectations. It gave me hope for domestic animation.

The greatest hope comes from its ability to weave a fresh narrative around a traditional story. If Wu Song’s tiger-slaying is a universally known classic theme, then simply recreating it in a film or TV work holds little meaning. What we want to see is a story about the refined, frail Wu Song facing a tiger, or Wu Song battling a fox spirit that transforms into a tiger—essentially, exploring new possibilities built upon traditional themes. “Tiger Returns” certainly manages to craft such a compelling narrative! Wu Xiaosong, a descendant of Wu Song, sets out to slay a tiger at Jingyang Ridge after his sister is captured by one. Like his ancestor, he’s a martial arts master. But unlike Wu Song, he encounters villains disguised as tigers to swindle travelers. The real tiger he seeks isn’t evil at all—it actually saves him. The beauty of crafting new tales from traditional themes lies in how audiences feel fresh suspense throughout the film. Uncertain of the ending from the beginning, they’re compelled to keep watching.

The difference between the old and new stories lies precisely in the core value of the new narrative. In the old tale, Wu Song killed the tiger, but in the new version, Wu Xiaosong apologizes to the tiger and reconciles with it. Why? Because he has come to understand the importance of coexisting harmoniously with animals. In the old story, Wu Song killed one tiger, but in the new story, Wu Xiaosong battles three fierce tigers. Why? Because more of these “tigers” are actually humans in disguise. The real tigers don’t want to harm people—it’s humans themselves who seek to cause harm. In the old story, Wu Song is an adult, but in the new one, Wu Xiaosong is a child. Why? Because children are the film’s primary audience—a stark departure from the novel “Water Margin.” Moreover, having a child grasp the importance of harmonious coexistence between humans and nature carries far greater significance than an adult learning this lesson.

The film’s central plotline is crystal clear: Wu Xiaosong sets out to rescue his sister, only to be saved by the very creature he believed to be the killer—the Tiger King. From the moment he arrives at the inn beneath Jingyang Ridge, Wu Xiaosong constantly flaunts his martial arts prowess, as if brute force could solve everything. It is only when he confronts the Tiger King that he realizes true strength lies in inner fortitude and cultivation, and he comes to understand the paramount importance of harmony. Wu Xiaosong is innocent; he feels fear, yet charges forward to save his sister. He makes mistakes—betraying Little Hedgehog to advance—but quickly repents. His purity starkly contrasts the ulterior motives of the adults he encounters, and it is precisely this innocence that makes him malleable.

Thus, if “Tiger Returns” embodying hope by crafting a new narrative is one message, the other hope it instills is that this new story possesses depth—one worthy of contemplation and rich in associations. This depth doesn’t refer to the film’s broad environmental theme—in fact, grand themes like environmentalism and human-nature harmony don’t inherently signify depth; in some ways, they can even feel superficial and contrived.

At this point, we must address some of the film’s flaws. One is its overly explicit exposition of moral lessons, as if the audience were too dumb to grasp them. Lines like “Humans are the real villains” are repeated three or five times. While this is undoubtedly a weighty line, such a powerful statement should be delivered just once at the most crucial moment—enough to shake the entire audience. There’s no need to hammer it home repeatedly, turning a stroke of genius into a mundane puddle. The most laughable moment comes when the tiger king utters platitudes about building a “harmonious society.” How utterly phony! Elevating themes isn’t done this way, nor is flattery delivered thus. Even mainstream films avoid such cringe-worthy expressions. Phrases like “harmonious society” are better left unsaid—let the audience infer them, let critics articulate them for you. When spoken aloud, they only alienate and repel viewers.

Why does the film insist on explicitly stating “harmonious society”? It reveals that the screenwriter and director still regard this as depth (beyond mere sycophancy, of course). In truth, environmentalism and harmonious society are merely themes for a work. Themes themselves do not equate to depth. True depth lies in what provokes profound reflection—such as human nature. Hayao Miyazaki’s films elevate environmentalism into profound territory because viewers deeply feel humanity’s cruelty toward nature and our own insignificance. He doesn’t shout it through dialogue; instead, he lets the camera language convey these truths. Our directors must stop committing this cardinal sin: spoon-feeding audiences what should be their own profound realizations through shallow, explicit means.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Tiger Returns 2010 Animation Film Review: Domestic Animation Sees the Dawn