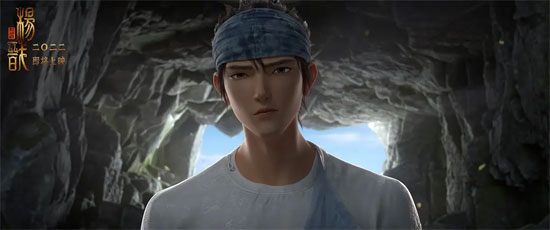

Film Name: 新神榜:楊戩 / New Gods: Yang Jian

Dropping this weekend, “New Gods: Yang Jian” (hereafter referred to as “Yang Jian”) had me itching with anticipation the moment its release date was announced. As a fairly loyal viewer of “Chasing Light Animation,” I couldn’t wait to catch it on Friday.

Technically, the film maintains its signature high standards—design, visuals, score, and art direction deliver constant surprises. Its relentless scene transitions and layered elements keep viewers’ eyes and attention constantly engaged, which is truly impressive.

Meanwhile, the plot of “Yang Jian” shows improvement compared to previous works—at least it no longer feels forced or awkward. However, it still lacks fluidity, and the narrative remains somewhat abstract, inevitably drawing criticism from many.

It’s clear that Zhui Guang Animation is striving to overcome its longstanding reputation for “strong visuals, weak storytelling.” The good news is that this effort has yielded some tangible results; the bad news is that it hasn’t yet led to a fundamental improvement… The more pressing question now is: While fans of Zhui Guang’s distinctive style can certainly continue to enjoy their work, how much longer can audiences with higher expectations keep waiting?

[Friendly reminder: Spoilers ahead.]

First off, I’ll start by gushing over the stunning art style of “Yang Jian” as usual.

If “New Gods: Nezha Reborn” was a “Fengshen-inspired, retro-futuristic cyberpunk reimagining,” then this film is a “luxury-inspired, xianxia-flavored steampunk take on the same mythos.”

The scene that left the deepest impression on me was the opening sequence showcasing the mythical island of Penglai. This island, built upon modern urban planning principles, underwent a three-dimensional futuristic transformation before being draped in a layer of ancient mythological aesthetics, achieving a uniquely distinctive integration of diverse design styles.

Some might find it a bit too “Frankenstein-like,” but I admire the creators’ ambitious pursuit. Take the scene where Yang Jian captures the fugitive: it transitions seamlessly from traditional street corner combat and alleyway battles to trendy mechanical flying chases, and finally to sci-fi-inspired traversals through floating air islands—it’s both fluid and visually striking.

Additionally, celestial abodes like Fanghu Island, Yingzhou Island, and the Golden Dawn Cave on Jade Spring Mountain each radiate distinct classical grandeur.

Building upon this foundation, the film incorporates numerous grounded modifications. For instance, Yingzhou Island features a bustling, street-market-style casino, while Fanghu Island hosts lively music troupes—all aligning with the premise that “after the Battle of the Gods, the celestial realm’s divine power is diminished, preventing immortals from freely flying.”

Beyond its grand vistas, “Yang Jian” delivers ingenious touches across numerous “smaller” details—characters, demonic beasts, props, and action sequences.

At the “Gas Station” (a mixed-energy refueling point), “Hand-Eyes” oversee labor while “Little Imps” serve as slaves. The Wind-Ear becomes a waiter in the casino. Within the remodeled jade palaces, celestial maidens once again perform aerial somersaults scattering flowers. Shen Gongbao and Chen Xiang’s coordinated combat dazzles the eyes. The Goddess of Wushan unleashes her beautiful yet deadly assault, while the mortal realm endures desolate decay and ceaseless warfare. The ink-wash 3D style of the Taiji diagram is reimagined…

Even a casual recollection floods my mind with stunning visuals, scenes, and characters—this is the film’s most commendable strength: nearly every ten minutes, it introduces fresh elements—be it novelty, eye candy, dazzling spectacle, or ethereal beauty—truly keeping audiences visually and mentally overwhelmed.

Thus I can confidently state that “Yang Jian” stands as a remarkably accomplished adventure film in terms of design and creation.

Now we must address the problematic character development and narrative structure.

Regarding the characters, the supporting cast is largely well-crafted: the persistent Chen Xiang, the resolute Wan Jun, the unrestrained Shen Gongbao, the rigidly traditional Yu Ding Zhenren, and others all feel vividly alive. Even secondary characters like the hot-headed Mo Lihai, the rigidly proper Mo Lihong, the taciturn Lao Yao, and the exuberant Xiao Tian are instantly recognizable through their words and actions. Ironically, it’s the protagonist Yang Jian who feels the least distinctive.

In terms of character positioning, Yang Jian—who descends into bounty hunting after sealing Mount Hua and closing his Heavenly Eye—is meant to embody a decadent, leisurely, and introverted rogue. His seriousness and inner fire require profound upheaval to gradually reignite. Yet the film portrays Yang Jian perpetually in passive motion, rendering his inherently elusive personality even less convincing.

Supporting characters only need to nail one aspect to stand out, while protagonists require multi-layered portrayal to reveal their essence. By this comparison, the film’s character development falls short.

Regarding the plot, this iteration of “Yang Jian’s” story shows progress compared to previous Sunlight Animation works. It features a coherent structure, well-grounded motivations, and avoids excessive absurdity or implausibility—all elements that remain reasonably plausible.

The film skillfully builds its narrative through Yang Jian’s quest and experiences, gradually revealing the story’s backdrop and character relationships. By blending elements of adventure and detective genres, it methodically unravels ambiguities and uncovers truths—a process that stands on solid ground.

The problem lies in the mismatch between the narrative pacing and the thrilling pace of the adventure. While the latter keeps audiences on the edge of their seats, the former feels overly cautious. This disconnect becomes particularly noticeable in the latter half, where the narrative stalls and falters. These cracks not only go unrepaired but widen over time, inevitably creating a sense that the plot and visuals are out of sync.

Additionally, while the motivations of several main characters seem sufficient individually, they become less coherent when combined, inadvertently falling back into the old trap of “effect preceding cause.”

That said, I must commend the core concept of “Yang Jian’s” story: the world operates in cycles. Whenever the universe’s momentum wanes, new forces surge in to reshuffle the deck. Jinxia Cave, having benefited from Yang Jian’s destruction of Taoshan in the previous cycle, now obstructs Chenxiang’s attempt to shatter Huashan. Upon realizing this truth, Yang Jian assists his nephew in fulfilling their familial destiny. Though chaos ensues, the world is reborn through destruction and renewal.

In an era where similar works proclaim “My destiny is mine, not heaven’s,” Yang Jian defeats those who exploit heavenly mandate for personal gain, thereby performing a ritual of “aligning with heaven’s will.” This offers a refreshingly original melody amidst increasingly homogenized fantasy narratives.

A minor gripe: the “Original Spirit” (Dharma Form of Heaven and Earth) concept introduced in “New Gods: Nezha Reborn” is further developed in “Yang Jian,” yet its execution feels underwhelming…

Logically, the successive appearances of Shen Gongbao’s Tiger-Sword Warrior, Chen Xiang’s Bamboo-Hat Youth, and the Four Heavenly Kings’ replica divine statues should have been satisfying enough. But then, during the final showdown, Yang Jian’s “Second Lord Zhenjun” form only got a few brief shots. Using his Mountain-Splitting Axe channeled with the power of the Mystic Bird, he defeated Jade Ding Zhenren and the three Heavenly Kings in a single move—logically, this feels realistic, but emotionally, such an anticlimactic design left me utterly unsatisfied.

Overall, “New Gods: Yang Jian” absolutely delivers value for the ticket price, and I still highly recommend it.

But I can’t help but add this: Neither creators nor audiences will settle for mere “visual splendor.” From White Snake to Green Snake, from Nezha Reborn to Yang Jian—how many more “practice runs” must Zheguang Animation undergo before achieving substantive growth? Let’s hope we won’t have to wait too long.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » New Gods: Yang Jian 2022 Film Review: Can Zui Guang Animation Go the Extra Mile?